On occasional weekend mornings, Kasmin shares essays and interviews that expand critically on the work and practice of the gallery artists. On the occasion of Les Lalanne: Zoophites, the ongoing exhibition in homage to the acclaimed French sculptors Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne drawn entirely from the collection of their eldest daughter Caroline Hamisky Lalanne, The Kasmin Review presents an original essay by exhibition curator Paul B. Franklin. This essay will be published in the forthcoming exhibition catalogue from Kasmin Books. Les Lalanne: Zoophites remains on view at 509 West 27th Street in New York through May 9, 2024.

Are they zoophites? What are the boundaries between plants & animals? Where does another order of things begin? What chain binds the Universe? But is there a chain?

—Voltaire, Les Singularités de la nature (1768)

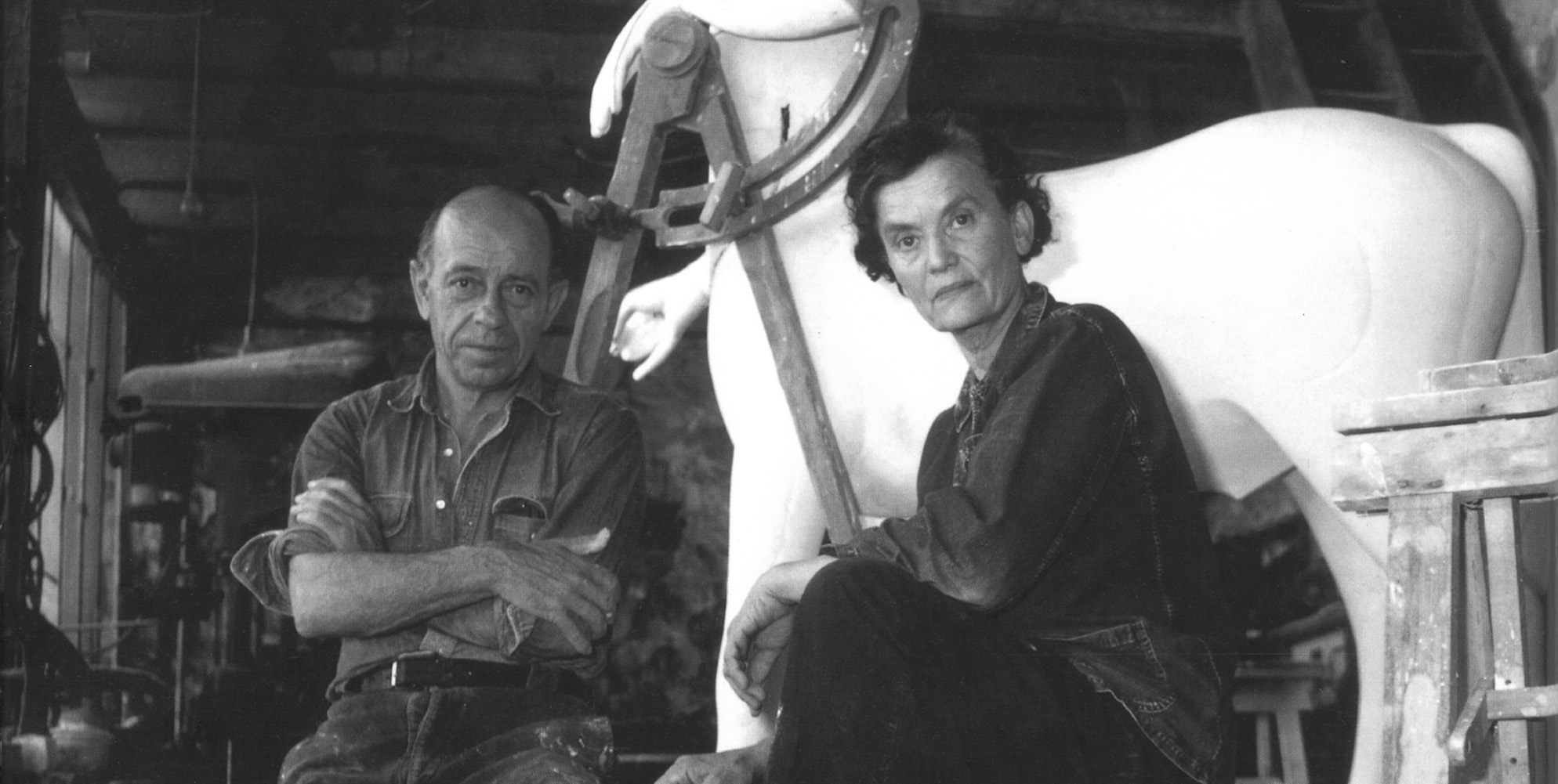

Despite France’s fabled republican motto liberté, égalité, fraternité, swathes of the populace remain wedded to hierarchies and enchanted with conveniently delineated categories concocted to keep both people and things in their place. The French expression mettre dans une case—which literally translates as “to put in a box” and signifies “to pigeonhole”—describes this propensity to judge someone or something summarily based on presumptions and prejudices. Even though the French are no outliers in succumbing to this all-too-human compulsion, its insidious and deleterious effects reverberate in everyday life across the country. The art world is no exception, as the work of Claude (1925–2019) and François-Xavier Lalanne (1927–2008) attests. From the moment that they burst onto the Parisian art scene in summer 1964, the couple at once beguiled and bewildered critics. Their unique, exquisitely handcrafted sculptures, the purely aesthetic pleasures of which are often bolstered by a touch of utility, have invariably defied expedient classifications. In so doing, Claude’s and François-Xavier’s vibrant universe of flora and fauna exposes—with brio and mirth—the utter arbitrariness, even the fatuity of the sacrosanct divisions that have circumscribed the fine and applied arts since the nineteenth century. In a review of their first exhibition with the Greek American art dealer Alexander Iolas, which opened at his Paris gallery on 27 October 1966 and coincided with the couple’s decision to adopt the collective moniker Les Lalanne to refer to themselves professionally, the young French art critic François Pluchart opined: “The exhibition of Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne is bound to confound. Are these works sculptures, decorative objects, works of art, intellectual diversions, or gadgets?”[1] Almost a decade later, Otto Hahn, one of the most respected and perspicacious art critics of his generation, apprised readers of the weekly news magazine L’Express: “Les Lalanne are difficult to classify: Can we describe them as sculptors, artisans, decorators, poets? All of these at once, no doubt.”[2] Such cogitations beleaguered Les Lalanne for decades. In the catalogue accompanying the 2021 exhibition Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne: Nature Transformed at the Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, curator Kathleen M. Morris acknowledged the recalcitrance of their metallic marvels to being corralled within a single, discrete rubric of artistic production:

Perhaps the biggest challenge was that of classification—where did their work fit in the recognized categories of art? . . . From the beginning of their joint career as exhibiting artists, this inability to find a suitable description of just what the Lalannes were producing has been a leitmotif. They have been called “unclassifiable,” their works landing somewhere between sculpture, decorative arts, and design. These questions have affected the museum world in particular.[3]

In 1998, François-Xavier confessed, not without merriment: “[Museums] don’t know where to put us.”[4] Claude concurred in 2017: “We are not very much appreciated by museums. I don’t think they really know how to categorise us or how to exhibit our work.”[5] Auction houses similarly evince astonishing intransigence in their parochial perception and public presentation of Les Lalanne’s output. Even as certain enlightened curators, critics, and art historians, among them Daniel Abadie, Daniel Marchesseau, Robert Rosenblum, and John Russell, have signaled the futility of retrograde and restrictive nomenclature to designate the artists’ singular creations, auction houses continue to consign—one might say to condemn—their work to sales rife with decorative arts and design.[6]

Les Lalanne repeatedly affirmed that the elusiveness and multivalence of their work hampered the employment of classical criteria to delimit their individual aesthetic projects. A fortnight before the inauguration of their 1966 exhibition with Iolas in Paris, François-Xavier performed an ingenious linguistic pirouette that highlighted this conundrum. While discussing his disquieting objects with a journalist from the New York Times, he proclaimed: “They are not furniture, they are not sculpture—just call them ‘Lalannes.’”[7] The French writer François Nourissier did exactly that in the jaunty text that he authored for the catalogue that Iolas published: “Les Lalanne make lalannes. Their audacious works are to the republic of objects what the pun is to the republic of words.”[8] In spring 1967, François-Xavier also announced in the American press: “We make sculpture with a function, aesthetics with utility.”[9] Some forty years later, Claude reflected on the predicament that her and her husband’s unorthodox approach to art making posed: “It was difficult to be accepted in the art world. We used to have a lot of trouble because we made useful things and made them ourselves. This is automatically considered as so called ‘decorative arts,’ a lesser, secondary art.”[10] She reiterated in February 2015: “I fear we have had du mal [a hard time], and been badly seen as artists, looked down upon, because of the fact that we made things which one could use. For a long time this wasn’t considered ‘art,’ and above all the problem was that our work was too well made, too crafted. If it had been rougher or just cruder it would have been so much better received!”[11] François-Xavier tempered the consternation voiced by his wife with lucidity and irony:

Since the beginning, we wanted to bring to sculpture, which is what you might call . . . “useless,” we wanted to bring to its nature the “useful.” Of course it also sometimes happens that our work is “useless” which can be beautiful as well! As our work is on the frontier between the “useful” and the “useless,” we can’t exhibit it in a practical context because then it’s immediately relegated in the hierarchy as being “useful,” a lesser category. So you have to exhibit your “useful” work in a “useless” gallery![12]

Claude ultimately avowed: “For us classification is of absolutely no interest but if forced to, we would say that, yes, we make sculpture.”[13]

At the outset of a declaration written in May 1961, pop artist Claes Oldenburg, a contemporary of Les Lalanne whose mischievous and malleable confections also subverted traditional conventions of sculpture, heralded: “I am for an art that does something other than sit on its ass in a museum.”[14] In their respective oeuvres, Les Lalanne pursued a similar objective. As François-Xavier confided: “We wanted to desacralize the work of art, to take it down from its pedestal.”[15] He likewise elaborated: “It amuses me to add a useful dimension to sculpture. Art has become over-sanctified in the West. Giving a practical use to a sculpture brings it back to the realm of the familiar and takes it off its pedestal. In the old days one could not think of a work of art without thinking of its usefulness.”[16] Near the end of her life, when asked whether she considered herself a craftsperson, Claude retorted: “Yes, sure, artists and artisans are the same thing. It is the same definition in the dictionary.”[17] In the catalogue of the 1977 group exhibition Artiste/Artisan? at the Musée des arts décoratifs in Paris, which featured one of Claude’s sculptures, François-Xavier advanced a comparable assessment in a series of provocative questions that foregrounded the porosity and absurdity of such a division.[18] By thwarting established art-historical hierarchies and thereby evading the cliché of mettre dans une case, Les Lalanne were in illustrious company. As William Morris, the English artist and artisan who instigated the British Arts and Crafts movement and its boundary-blind practices, proffered in 1892: “Art is the expression of man’s pleasure in labour.”[19] Like Les Lalanne, Marcel Duchamp—whom the couple got to know in his twilight years and whose wife, Alexina, and stepdaughter, Jacqueline Matisse Monnier, became their lifelong friends and neighbors—never relinquished his reliance on handiwork, even after envisioning the readymade in 1914 and forsaking easel painting in 1918. Throughout his life, in fact, he embraced the bricoleur (tinkerer) and his counterpart, the craftsperson, as foils for the artist, alleging in 1966: “Now everyone makes something, and those who make things on a canvas, with a frame, they’re called artists. Formerly, they were called craftsmen, a term I prefer. We’re all craftsmen, in civilian or military or artistic life.”[20] In a more personal and ardent tone, Duchamp divulged to the French art critic and curator Michel Tapié the unbridled self-fulfillment that he experienced after accomplishing an undertaking with his own two hands: “Manual confirmation is a source of joy, an obsession.”[21]

With prowess and tenacity, Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne charted an inimitable path in the history of art during their more than half a century of aesthetic engagement. Les Lalanne: Zoophites pays homage to their incontrovertible achievements as artists. It also happens to be the first exhibition conceived with this explicit intention since the death of Claude in spring 2019 at the age of ninety-three. To that end, the thirty-five artworks on display come directly from Les Lalanne’s estate, all of which Claude’s eldest daughter, Caroline Hamisky Lalanne, has graciously provided for the occasion.[22] Such an exceptional assemblage, including three rare collaborative pieces alongside several iconic masterworks, demonstrates the rich scope of their production in which meticulous artistry and artistic invention were indivisible. In their particular conception of art making, Les Lalanne emulated Old Masters like Nicolas Poussin, the patriarch of French classicism and one of François-Xavier’s idols, who purportedly declared: “Ce qui vaut la peine d’être fait vaut la peine d’être bien fait” (What’s worth doing is worth doing well).[23]

In a further tribute to Les Lalanne, the present exhibition takes its title from the couple’s maiden “joint solo show,” Zoophites (25 June–15 October 1964), which took place in Paris at Galerie J, 8 rue de Montfaucon, in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. The event was advertised in the form of a modest black-and-white rectangular announcement.[24] A gifted wordsmith, François-Xavier devised the title, an alternate spelling of the antediluvian French scientific term zoophyte, which, since at least the mid-sixteenth century, had primarily designated marine invertebrates (comb jellies, corals, true jellyfish, sea anemones, sponges, etc.) that mimic plants in their appearance and attributes.[25] These enigmatic creatures offered the perfect metaphor for Les Lalanne’s earliest sculptures, composed principally of motifs culled from the natural world.

Galerie J was an upstart establishment that Jeannine (also written Jeanine) de Goldschmidt-Rothschild (née Petit) had launched in May 1961. Thanks to her efforts and those of her romantic partner and future husband, the art critic Pierre Restany, this exhibition space rapidly distinguished itself as an important venue for emerging artists, especially those affiliated with Nouveau Réalisme, a burgeoning, albeit eclectic, movement for which Restany served as impresario.[26] These figures included Arman, César, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, Raymond Hains, Yves Klein, Niki de Saint Phalle, Daniel Spoerri, Jean Tinguely, and Jacques Villeglé, some of whom had been close friends of Les Lalanne since the 1950s. From 1949 to 1960, in fact, François-Xavier rented a rustic atelier at 11 impasse Ronsin, an artists’ enclave in Montparnasse. Claude joined him there around 1954, shortly after they became a couple. The warren of ramshackle edifices had attained notoriety due to Constantin Brancusi, who lived and worked there from 1928 until his death in 1957.[27] Les Lalanne’s studio was contiguous to that of the aged, often cantankerous Romanian sculptor, and they socialized regularly.[28] They also befriended many of their other artist neighbors, not to mention certain frequent visitors, namely William N. Copley (resident 1952), Max Ernst (resident 1953–55), Jean Tinguely (resident 1955–63) and his first wife, Eva Aeppli (resident 1955–60), James Metcalf (resident 1956–65), Niki de Saint Phalle (resident 1960–63), Yves Klein, and Daniel Spoerri.[29] In this bustling community of creative types, proximity to the elderly Brancusi anchored and emboldened its more fledgling tenants, as Copley avouched in 1952: “The name of Brancussi [sic] is one of the most venerated in the world of modern sculpture. . . . His presence is something more than a reassurance to the artists here; it’s a solid inspiration. It makes us think that it may be worthwhile painting pictures or sculpting stones after all.”[30]

Opposite Les Lalanne’s atelier, Metcalf—an American sculptor with a passion for and extensive expertise in multiple metal-working techniques—had set up his workshop in the studio formerly occupied by Copley and Ernst. In 1962, he introduced Les Lalanne to Goldschmidt-Rothschild, with whom he was or had been romantically involved, and she agreed to present their work at Galerie J.[31] Metcalf had previously coaxed the couple to explore the aesthetic possibilities of metal, teaching them to solder and weld.[32] In tandem with Metcalf, Claude took up electroplating (galvanoplastie in French), an outmoded nineteenth-century process whereby materials or objects are coated with a thin layer of metal while submerged in an aqueous salt solution charged with electrical currents and composed of the alloy to be deposited. (Between 1950 and 1954, Duchamp had resuscitated the same antiquated technique to fabricate several copper-electroplated plaster casts, known as the erotic objects, which resemble unoxidized bronzes.)[33] Decades later, Claude expressed gratitude for Metcalf’s pivotal role in her apprenticeship:

Jimmy knew at least half of the galvano technique, and I knew the other half, so we were a perfect team to find out all about it together. . . . So here at the Impasse [Ronsin] we experimented together, he already knew more than me, and we learnt together about the chemical baths, how to vaporize metal and make it conduct electricity. . . . I think [I] gave the very first galvano work I made to Metcalf, it was a small choupatte and he deserved it as a present; I would never have made it without him.[34]

As part of Zoophites at Galerie J, one of the thirteen pieces that she exhibited was a clock titled Hello Jim (current whereabouts unknown), in honor of Metcalf.[35]

In 1990, Claude reflected on the remarkable promise of metal as a medium, a revelation prompted by the example and encouragement of Metcalf: “When we started working with metal, I was very surprised. The rods can be heavy, the blowtorch burns, but the material itself is quite easy [to use]: you can saw it, melt it, bend it, shape it, and deform it, which is really wonderful, even though it’s rather hard.”[36] For the catalogue issued in conjunction with Zoophites at Galerie J, Metcalf penned a testimonial, extolling his friends’ innovative creations:

As Les Lalanne’s neighbor in impasse Ronsin . . . I had the good fortune to witness their prodigious evolution, and the experience acquired during this rapid ascent has enabled them to present today an admirable exhibition of contemporary objects that are useful only insofar as they can be used. I am convinced that this exhibition will help restore Paris to its international position as a producer of Significant Art. . . . François Xavier [sic] and Claude Lalanne, marrying ancient and modern techniques with the courage that distinguishes the Artist from the Artisan, have created objects “to live with” that defy seriality and are essentially as individual and singular as each of us.[37]

In his review of Zoophites, the American poet and art critic John Ashbery observed: “The rhinoceros is turning out to be an avant-garde animal. Both Dali [sic] and Ionesco have been fascinated by its symbolic possibilities, and now a sculptor, François Lalanne, has produced an almost life-sized one in sheet metal which dominates the group show at the Galerie J.”[38] The beast in question was none other than Rhinocrétaire I (1964), its title a witty French contraction formed from rhinocéros (rhinoceros) and secrétaire (secretary), a hinged, fall-front desk earmarked for writing correspondence and storing letters and documents. Constructed from sheets of hammered and welded brass, the sculpture required months of arduous labor to complete and, therefore, was François-Xavier’s lone contribution to the exhibition.[39] Enthroned in front of the gallery’s large plate-glass window, his handwrought variation on the zoophyte beckoned passersby. The articulated left shoulder flank, midsection, and hindquarters of its carapace were open, revealing its reimagined entrails—a desktop with a nearby electric lamp; a kind of countertop; two alcoves reserved for books and separated by a second recessed light source; drawers, shelves, and cubbyholes of various shapes and sizes; a safe; a bar with circular compartments beneath it for depositing bottled alcoholic beverages, etc. The artist had equipped the latter receptacles with removable round lids to maintain decorum and internal crescent-shaped drawers to expedite access. Jutting from the mammal’s snout was an actual rhinoceros horn. François-Xavier had attached it to a brass replica, which he had secreted inside the hollow nasal cavity. The twin defensive projections, therefore, could be inverted at will, a gesture that recalls one of the requisite movements of a cocktail shaker in order to make appetizing admixtures at the bar located in the rump.[40] The surfaces of the brass sheets comprising Rhinocrétaire I and the prominent welding seams that bind them together mimetically represent the pachyderm’s thick skin, its furrows, pleats, and wrinkles conjuring riveted plates of armor. As François-Xavier wryly contended: “[A rhinoceros] has a skin so tough that it forms huge scales. Morphologically speaking, these plates are easy to separate one from the other. They open up like a suit of armor. My rhino is the precise copy of a one-year-old male. But he is well mannered.”[41]

The rhinoceros rapidly assumed the status of a totem in François-Xavier’s oeuvre. In subsequent years, he realized multiple iterations of this herbivore in drawings, prints, and sculptures on both outsized and Lilliputian scales. The bronze Grand Rhinocéros V (1994/2000) is the ultimate monumental incarnation of the animal. With its lush ebony patina, the resplendent quadruped differs from most of its antecedents in that it is a conventional sculpture, entirely devoid of any functional resonance. As such, it brings to mind the formidable casts of nineteenth-century French animaliers, like Alfred Jacquemart and his colossal cast-iron Rhinocéros (Rhinoceros, 1878)—commissioned for the 1878 Exposition universelle, installed from 1935 until around 1985 in the gardens of the Porte de Saint-Cloud on the southwestern edge of Paris, and now enshrined in front of the Musée d’Orsay—or Auguste Cain and his bronze Rhinocéros attaqué par un tigre (Rhinoceros Attacked by a Tiger, 1882), a grisly portrayal that stands in the otherwise picturesque Tuileries Garden.

François-Xavier conceived Grand Rhinocéros V in 1994 and envisioned issuing it in an edition of eight copies. He eventually abandoned this idea, and the present sculpture is the sole example that he executed. Its sleek, bulbous surfaces punctuated with geometric volumes exemplify his signature style. Such a scrupulous and rhythmic economy of means imbues Grand Rhinocéros V with an arresting presence. François-Xavier’s bronzes Grand Bouquetin (1999/2016) and Wapiti (petit) (1988/1999) exude similar force and quietude. As Claude recognized in 2000: “François-Xavier knows how to combine the elegance of drawing with the rigor of form. It’s true that what’s well-conceived is clearly formulated, and this postulate perfectly defines his character.”[42] His mastery of line and distillation of form resonated with Brancusi who strove to visualize “the essence of things,” as he characterized his aesthetic project, one that also spawned a veritable bestiary, including the series Le Poisson (Fish, 1922–30), L’Oiseau dans l’espace (Bird in Space, 1923–41), and Le Coq (Cock, 1924–52), as well as the individual sculptures Deux Pingouins (Two Penguins, 1911–14?), Trois Pingouins (Three Penguins, 1911–12), L’Oiselet (Young Bird, 1925), L’Oiselet (Young Bird, 1928), L’Oiselet II (Young Bird II, 1928), Le Miracle (Phoque I) (The Miracle [Seal I], ca. 1930–32), Tortue volante (Flying Turtle, 1940–45), La Tortue (Turtle, 1941–43), and Phoque II (Seal II, 1943).[43] Brancusi displayed several of these creatures in his atelier during Les Lalanne’s stint in the impasse Ronsin. In the same vein as his predecessor, François-Xavier disclosed in 1990: “Animals have always fascinated me, perhaps because they’re the only beings through which we come into contact with another world. . . . No being on earth is capable of such great immobility as a wild animal. An immobility so absolute that, in their natural environment, they can become invisible. . . . This gift that animals have is so perfect that it seems as if they literally step out of time and into eternity.”[44] The regal beasts that constitute François-Xavier’s sculptural menagerie kindle the same dazzling effect.

In his innumerable sculptural ruminations on the rhinoceros, François-Xavier almost exclusively represented the single-horned species native to the Indian subcontinent. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the exotic mammal returned to the shores of Europe for the first time on 20 May 1515, when an Indian rhinoceros disembarked in Lisbon as a diplomatic offering from Muzaffar Shah II, the Sultan of Cambay (in present-day Gujarat), to Manuel I of Portugal. A few months later, the Portuguese monarch regifted the animal to Pope Leo X, eager to curry favor with the pontiff.[45] A few written accounts and elementary renderings of the behemoth circulated swiftly across the Continent, including in Germany, where Albrecht Dürer produced the woodcut Rhinoceros (1515). His fantastical depiction of the pachyderm—complete with a spiral hornlike dorsal protuberance and a mélange of cuirassed and reptilian skin—became one of the earliest, most renowned, and most widely disseminated icons of nascent European print culture.[46] This acclaimed woodcut often is associated with François-Xavier’s rhinoceroses. Another equally compelling French precedent for his series, one that critics, curators, and scholars have heretofore overlooked, is Clara the Rhinoceros (1749) by Jean-Baptiste Oudry, a celebrated animal painter and a regular recipient of royal commissions under Louis XV. In this spectacular, stunningly realistic canvas, which measures 119 11/16 × 178 3/8 inches (304 × 453 cm), the artist painted a life-size portrait of Clara, a female Indian rhinoceros who arrived in Rotterdam on 22 July 1741 and crisscrossed Europe with her Dutch keeper until her death in 1758, captivating the curious and catapulting to international eminence.[47] Unveiled at the Salon of 1750, Clara the Rhinoceros was quickly copied by other European painters and printmakers.[48] In his successive treatments of the rhinoceros, François-Xavier underscored the animal’s venerable presence in Western art history, just as Salvador Dalí had done before him and Walton Ford would do after him.[49]

From the debut of their artistic careers, Les Lalanne manifested antithetical working methods. “If we were to be compared to musicians,” François-Xavier confessed, “my wife would improvise while I would have to write out my part before playing it.”[50] In the second half of the 1940s, he had matriculated at the Académie Julian in Paris, a storied private art school where he nurtured an aptitude for draftsmanship and composition, both of which garnered him early accolades. The institution, for instance, awarded the budding painter its annual art prize on 5 July 1948, as well as first prize on 27 June 1949 in its special competition to commemorate the centennial of Frédéric Chopin’s death.[51] On the occasion of the former honor, a French art critic announced: “François Lalanne’s paintings are solid, well-constructed, adorned with a robust earthen color, and contain no hint of the arbitrary or the accidental.”[52] The artist brought the same technical rigor to the step-by-step conception and execution of his sculptures, commencing with preparatory drawings followed by full-scale enlargements on kraft paper, three-dimensional models, metal armatures, etc. Claude, on the other hand, worked intuitively, granting free rein to her unconscious, like her surrealist forebears. “How things are made, I couldn’t say,” she admitted in 1990. “They come as they come, over time, from the hand, from the eye, from work. There are so many things that I never would have imagined before soldering, filing, melting, and hot retrimming with a blowtorch.” Claude also conceded:

I’ve always had an eye for things that would probably be of no interest to anyone else. . . . In the studio, I keep at hand for a long time a jumble of heterogeneous metal, casts, forms, petals, stems, which would say nothing to anyone but which convey something for me. I don’t know what, until the moment when they emerge of their own accord, perhaps years later. It’s as if I had to wait for the instant of true encounter. You can’t rush into a dialogue with things. . . . When I begin, I never know what I’m going to do.[53]

Propelled by the desire to discover “the particular forms of familiar things,” as she summarized her artistic ambition, Claude largely plucked elements for her work from her immediate environment, its bounty ranging from foliage, vegetables, and fruits to barnyard animals, local wildlife, insects, and even anatomical parts molded directly from the bodies of family and friends.[54] The often unexpected and incongruous combinations that coalesced organically in her sculptures suggest what André Breton designated as beauté convulsive (convulsive beauty).[55] This phenomenon, “another term for the Marvelous,” as art historian Rosalind E. Krauss has argued, was indebted to Isidore Ducasse’s prose poem Les Chants de Maldoror (1868–69), a foundational text in the history of surrealism in which the French poet, writing under the pseudonym Comte de Lautréamont, famously likened beauty to “the fortuitous encounter on a dissection table of a sewing machine and an umbrella.”[56]

In Zoophites, Claude presented two diminutive versions of Choupatte, a metal sculpture à la Lautréamont, which was composed of a head of cabbage set atop two chicken shanks and feet. In his review of the exhibition, Ashbery remarked that the jarring juxtaposition appeared “as though it had stepped out of a painting by Bosch.”[57] Its title, a composite of chou (cabbage) and patte (foot), reiterated the zoophytic aspect of the hybrid piece.[58] Like the rhinoceros in François-Xavier’s oeuvre, Choupatte, which Claude reprised on numerous occasions and on widely diverse scales, is one of her most emblematic works. As François-Xavier declared: “The cabbage leaf is to Claude what the acanthus leaf was to Greek art!”[59] In its sheer strangeness, Choupatte also shares a lineage with Meret Oppenheim’s surrealist objects. Ma gouvernante (My Governess, 1936), for example, consists of a pair of women’s white leather shoes corseted together with string and lying upside down on a metal platter with their heels bedecked in decorative paper frills like those utilized in posh presentations of poultry, lamb chops, and pork chops. Similarly, Tisch mit Vogelfüssen (Table with Bird’s Feet, 1939) comprises a gilded oval wooden tabletop with multiple traces of bird’s feet carved in relief across its surface and mounted on a pair of avian appendages in gilt patinated bronze, which the artist fashioned after plaster casts. Jeannine de Goldschmidt-Rothschild had acquired the latter object directly from Oppenheim sometime in the 1950s or 1960s, and Claude may well have been aware of its existence when she conceived Choupatte.[60] Claude further elaborated the zoophytic and surrealist tenor of Choupatte in her small bronze Lapin Chou III (2000/2012), in which cabbage leaves sprout from a rabbit’s hindquarters and posterior at the same time that a cabbage stem protrudes from its neck and portions of its pelage mimic the textured pattern of the green vegetable. Embodying the nebulous metamorphosis of fauna into flora or vice versa, this sculpture is one of several variations on the theme that the artist created after a rare early drawing published in summer 1970 in The Paris Review.[61]

In the late 1960s, when Yves Saint Laurent incited Claude to work on a larger scale, she realized a sculptural duo that evoked Choupatte: a seated male nude titled Homme à la tête de chou (1968), which French singer-songwriter Serge Gainsbourg purchased and which inspired his 1976 concept album L’Homme à tête de chou, and a standing pregnant female nude christened Caroline enceinte (1969), both with Milan cabbages in lieu of heads.[62] The former is a life-size rendering of Bernard Monnier—Claude’s neighbor and the husband of her friend Jacqueline Matisse Monnier—while the latter portrays her eldest daughter, Caroline Hamisky Lalanne, who was carrying her first child at the time. These ambitious artworks were based on a series of elastomer molds of every portion of the subjects’ bodies, a crucible both for them and for the artist. Claude subsequently duplicated these many molds in wax, electroplated the impressions in copper, and welded together the resulting metal casts to construct each figure. As François-Xavier had done in Rhinocrétaire I, she purposefully left the seams visible. Even if art historians and curators rightly associate Homme à la tête de chou and Caroline enceinte with contemporary artistic practices of imprinting and casting parts of the human body (think Jasper Johns, Yves Klein, Bruce Nauman, and George Segal), these sculptures also emulated the work of Auguste Rodin.[63] In a process known as marcottage, the legendary French sculptor confected experimental assemblages from a vast inventory of unpolished plaster bodily fragments on which the joins were left exposed and the physical traces of their consolidation were readily apparent. The artist thus proposed a modern meditation on the Renaissance technique of non finito, which Michelangelo, one of his heroes, so deftly had exploited.[64] In effect, Homme à la tête de chou and Caroline enceinte closely resemble Rodin’s Assemblage: masque de Camille Claudel et main gauche de Pierre de Wissant (Assemblage: Mask of Camille Claudel and Left Hand of Pierre de Wissant, ca. 1895). The same is true for two other sculptures by Claude in the present exhibition: Ex-voto (late 1970s), an oxidized copper-electroplated cast of the shoulder and upper arm of an unidentified individual with a large Milan cabbage leaf grafted to its verso, and Portrait cubique d’Alexandre Iolas (1974), a bronze likeness of Alexander Iolas.[65] With eyes closed and a stoic expression, the art dealer’s effigy is redolent of a death mask. In its macabre commingling of the living and the lifeless, the portrait recalls the allure that postmortem facial imprints had for French surrealists, like Breton and Paul Éluard, both of whom enlisted their sculptor friend René Iché in 1929–30 to execute plaster casts of their inanimate visages. Portrait cubique d’Alexandre Iolas is part of a series of portrayals of Claude’s male friends, which included Karl Lagerfeld and Daniel Spoerri, their blocky and truncated geometric forms harkening back to carved fragments of ancient Greek atlantes or herms.

In many of her sculptures, Claude focused exclusively on botanical motifs, which she interlaced with aplomb. Although Banc Williamsburg (1985/2011), with its series of swordlike bowed leaves of yellow iris, is a prime example, Les Berces adossées (2015) is one of the most spectacular. A tour de force of technical sophistication and visual harmony, this majestic bench instantiates an admission that Claude made in 1990: “I love simple lines and sometimes create very complicated shapes. In sculpture, as in life, I believe you have to be strong and, above all, not too sentimental.”[66] For the legs and crossbars, she employed the fluted stems of Heracleum mantegazzianum (giant hogweed), “so regular that it’s easy to bend them,” as she reported with satisfaction.[67] Known in French as berce du Caucase (Caucasian hogweed), this hearty but noxious weed can exceed fifteen feet in height, with its hollow, sturdy stems measuring two to six inches in diameter. If its toxic sap comes into contact with human skin and sunlight, blisters, burns, and rashes ensue. The artist augmented her stem structure with a seat and back support in the form of eight enormous ginkgo leaves, the intricately veined blades of which accent the fluting of the giant hogweed stems. Claude oriented the leaves slightly to the left or to the right, as if they were fluttering in the breeze. Their stylized stalks are entangled in a network of sinuous tendrils that serve as armrests at their extremities. The complexity of the ensemble can be fully grasped only when Les Berces adossées is viewed in the round, rather than adossé (sitting against or abutting) a wall like a generic utilitarian bench. In point of fact, the French adjective adossé also translates as “back-to-back,” alluding to the necessity of circumambulating Les Berces adossées in order to admire all sides.

The ginkgo leaf entered Claude’s visual repertoire in or immediately before 1990, when the American architect Leo A. Daly III and his wife, Grega, collectors and friends of Les Lalanne, gathered samples of the fanlike foliage during a sojourn in Japan and presented them to the artist.[68] The luminous saffron-yellow hue that the ginkgo leaf attains in autumn mirrors the shimmering gilt patinated bronze of many of Claude’s creations. Native to East Asia, Ginkgo biloba—a vigorous single species with no known relatives that has survived essentially unchanged for some 200 million years, with certain specimens living upwards of a millennium—is a sacred tree in Chinese, Japanese, and Korean culture, symbolizing longevity, prosperity, and resilience.[69] Furthermore, its double-lobed (biloba) leaf denotes love, as Johann Wolfgang von Goethe attested in his verse “Ginkgo biloba” (1815), which he sent to his beloved, Marianne von Willemer, with two ginkgo leaves collaged to the page: “Is its leaf one self divided, / Forked into a shape of strife? / Or have two of them decided / On a symbiotic life? / This I answer without trouble / And am qualified to know: / I am single, I am double, / And my poems tell you so.”[70] The ginkgo leaf is also a befitting hallmark of the amorous and artistic union of Les Lalanne, the couple’s indivisibility on par with the two giant turtledoves that form a single entity—members of this species mate for life—and appear to envelop one another tenderly in François-Xavier’s Double Tourterelle (1998/2001), which doubles as a love seat.[71] Even though Les Berces adossées is a unique piece, Claude integrated ginkgo leaves into several other series, such as Ginkgo trifolia (ca. 2000/2010), Chaise ginkgo (1996/2018), and Bambiloba II (2005/2012), all featured in the present exhibition. The latter signals the ginkgo tree by way of its title, a portmanteau of “bamboo” and “biloba,” and the two gargantuan bilobed leaves that overlap to form the settee.

The exacting naturalism of Claude’s depictions of ginkgo leaves and giant hogweed stems in Les Berces adossées contrasts with her more schematic approach to plant life in Arabesque (2018). One of her last works, the imposing sculpture was undertaken as a private commission to hang on a wall bordering a swimming pool. The client, impatient with Claude’s measured progress on the bronze, rescinded the order before the artist had completed it. The undulating boughs of the arabesque are ornamented with plain lobed leaves that echo the vividly rudimentary foliage that Henri Matisse clipped from colored sheets of paper and incorporated into his cut-outs. The resolute simplicity of Claude’s line also calls forth her early drawings, like those published in summer 1970 in The Paris Review.[72] Throughout her oeuvre, the artist had repeatedly composed cadences analogous to that between branches and leafage in Arabesque. The serpentine support accented with candle nozzles that comprises Candélabre (sans feuilles) (1999/2014) is a quintessential example.

Whereas Rhinocrétaire I and Grand Rhinocéros V are nearly life-size representations of two exotic quadrupeds, their cousin Grand Chat polymorphe (1998/2008), which measures over ten feet long and more than six feet tall, is a genuine colossus based on a common house cat. François-Xavier executed the original version in 1968 at the behest of the French architect Émile Aillaud and his wife, Charlotte, who was the elder sister of Juliette Gréco. In the hope of animating the couple’s swanky Parisian abode, he expressly conceived the feline, one of his largest sculptures to date, to be “just a little too big.”[73] As François-Xavier justified in 1966: “The places where people live need not be boring. And artists need not be boring.”[74] With a wink and a nudge, Grand Chat polymorphe was the heir of Lewis Carroll’s Cheshire Cat, the latter’s perpetually puckish grin belying the sage counsel that it preached in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865).

François-Xavier constructed Grand Chat polymorphe incrementally, as he had done with Rhinocrétaire I, welding together sheets of brass over a steel skeleton. The present exemplar, made of bronze, is the fifth and final version in a projected edition of eight, which remained incomplete owing to the death of the artist. François-Xavier’s treatment of the cat as a polymorph is reminiscent of the inscrutability of a zoophyte. As he noted in 2008 with regard to the sculpture: “‘A cat has nine lives.’ This one seems to be living them all at once—a cat, a bird, a horse, a she-wolf, a pig, a fish.”[75] The tabby’s rotating head sits on a generic mammalian trunk, its legs displaying the cloven hooves and dewclaws of ungulates, like pigs or cattle. A tail fin, however, extends from its hindquarters, and two lateral panels open outward like wings, adding aquatic and avian elements to the hybrid beast. Grand Chat polymorphe also manifests sexual polymorphism. While the feline is identified as male in the title (chat in French), the eight swollen teats bulging from its belly distinguish it as a chatte (female cat). A mother’s milk is the primary source of sustenance for young mammals, including humans. Furthermore, François-Xavier’s evocation of a she-wolf in his description of the artwork conjures the wildly popular Roman legend in which this four-legged carnivore suckled Romulus and Remus, the mythological twins associated with the founding of Rome, a scene ubiquitously rendered in the history of art, most notably in the bronze Capitoline She-Wolf (fifth century BCE/late 1500s). Like its canine counterpart, Grand Chat polymorphe offers equivalent nourishment to adults, in the form of alcohol, which can be dispensed once the polymorph’s wings are unfurled and the bar occupying its innards is accessible. To facilitate the distribution of intoxicating libations, François-Xavier tucked inside the cat’s torso four metal trays that pivot outward and flank the wings, along with a few compartments and an ice bucket inset in the bar top that stretches the internal length of the abdomen. He eliminated all of these accoutrements from the 2008 edition.

When first unveiled, Grand Chat polymorphe and its immediate successor, Lapin polymorphe (1969)—a rabbit with a rotating head, single-toed hooves, wings with fins at their tips, two dorsal curls that mime the upturned tail feather of a drake (male duck), and an incised back, perhaps hinting at the segmented exoskeleton of an insect—were routinely characterized as “monsters,” due to their polymorphism. In an article titled “The Fashions: Nice Monsters and Gold Fingers” and published on 8 January 1968 in Women’s Wear Daily, a trade journal of the American fashion industry, François-Xavier specified that his winsome, wild things were gentils (nice). “I hate nightmares,” he expounded, “so I did them pretty.”[76] Several photographs illustrated the feature, and they most likely were the first visual documentation of the sculptures to circulate publicly.[77] In view of the date of the publication and the appearances of the artworks in question, the images show preparatory models of the chimerical animals rather than the definitive sculptures. The supposed monstrosity of François-Xavier’s polymorphs demonstrates the central role of such heterogenous creatures—often invested with magical powers—in folk, fairy-tale, and mythological narratives, such as those constituting Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Grand Chat polymorphe and Lapin polymorphe, for instance, are not dissimilar from lamassu, a protective Assyrian deity with a male human head, sporting a long beard and horned cap or crown, on the winged body of a bull or lion. Several ancient monumental sculptures of lamassu dominate the galleries housing Assyrian art in the Musée du Louvre, rooms that François-Xavier dutifully patrolled from December 1949 until March 1950, when he worked as a guard at the institution.[78] During this same period, he developed a fondness for another antiquity in the Louvre’s permanent collection and also under his supervision, the hallowed Egyptian Apis Bull (ca. 379–361 BCE).[79] François-Xavier adapted the bovine’s streamlined yet hulking frame years later in his bronze Taureau II (1992/2007), a farmyard pendant to Rhinocrétaire I with a hinged right midsection that folds down to reveal a leather-covered desktop, shelf, and cubbyholes. Apropos her husband’s sculptural fictions, Claude acknowledged: “He dreams wide awake and invites us to do the same before his completed sculpture.”[80]

Alongside François-Xavier’s brimming bestiary of domestic and feral creatures, the crocodile was virtually the sole exotic animal to pique Claude’s creative interest. Over the years, she communicated slightly different anecdotes regarding her initial acquisition of the reptile in the early 1970s. In one account, beneath a moonlit midnight sky, the director of a zoo surreptitiously presented to her a wax mold of the ferocious predator.[81] In a similar chronicle, this same unnamed individual, identified merely as a friend of Niki de Saint Phalle, heeded Claude’s entreaty and summoned her to the zoo under the midnight light of a full moon to recuperate the cold-blooded carcass of a recently deceased specimen.[82] Finally, in 1990, the artist divulged that the crocodile had been “offered by the Jardin des Plantes,” a historic Parisian institution comprising the headquarters of the Muséum national d’histoire naturelle and a botanical garden (located on the same site), as well as a neighboring zoo.[83] Despite being tinged with apocryphal elements, the first two reports illustrate that the reptile assumed the importance of a fetish for Claude. She even went on to acquire an adult taxidermic example that hung high on a wall inside the porte cochere of her and husband’s home-studio in Ury.[84] As Daniel Marchesseau maintained, the crocodile was to Claude “what the elephant skull was to Henry Moore: an inexhaustible source of inspiration.”[85] After electroplating a juvenile specimen in copper, Claude fabricated her first Fauteuils Crocodile in 1972 and revisited them well into the 2010s in several bronze and aluminum variations, including Crococurule (1992/2013) and Bureau Croco (2007/2017). The former consists of a crocodile hide draped over a curule seat, both in aluminum. A familiar furnishing in ancient Rome, the curule was reserved for magistrates invested with imperium, a type of authority, and its appearance in Roman visual culture symbolized military or political power. With its imperial connotations, the curule enthralled Napoleon I and was a popular component of the French Directoire style (1789–1804). Originally destined for couturier Tom Ford, the bronze Bureau Croco features a rectangular desktop partially covered and trimmed with several crocodile skins, their irregular forms and textures contrasting with the elegantly curved legs and crossbars, both of which derive from giant hogweed stems.

Claude’s inveterate fascination with the crocodile paralleled the mystical position that this reptile occupied in the mind and memory of Brancusi. In summer 1924, while the Romanian sculptor was swimming in a river near Fréjus on the French Riviera, he was swept away in an unexpected torrent. As he struggled to stay afloat, a piece of cork oak came within his reach. The form of the flotsam resembled that of a miniature crocodile, and its craggy, creviced surface recalled the reptile’s rugged, scaly skin. He grasped the ersatz life preserver, and it carried him down the rushing tributary to the safety and calm of the beach in Fréjus.[86] Following this near-fatal mishap, Brancusi assembled a makeshift shrine in honor of divine providence. On an isolated stretch of shoreline, where three wooden poles had been placed upright in the sand, he adorned the central trunk with the precious cork-oak curio that had miraculously saved his life. He further festooned the treasure with a necklace of ten disk-shaped amulets that had been whittled from cork and strung together on a length of rope. “After I placed the crocodile on the temple,” he recollected, “I ran into the water like a seal, shouting ‘Bravo, crocodile!’”[87] Brancusi also immortalized the ephemeral, site-specific installation, which he dubbed Le Temple du crocodile (Temple of the Crocodile), in a series of photographs. Intensely superstitious, he ultimately transported the relic back to Paris and mounted it in the upper corner of one of the rooms of his studio in the impasse Ronsin. Les Lalanne undoubtedly noticed the conspicuously displayed oddment during one of their frequent visits to Brancusi’s atelier in the mid-1950s. Given that the Romanian sculptor had a penchant for storytelling, he also almost certainly regaled the couple with his tall tale of the magical driftwood crocodile that became his savior.[88]

The collective denomination Les Lalanne, which Claude and François-Xavier adopted in 1966, periodically generated confusion. As Claude observed: “People have this misconception that we collaborate together the whole time when in fact we have two distinct, separate oeuvres.”[89] On a few exceptional occasions, however, Les Lalanne joined forces and worked in concert. Three of their collaborations are part of the present exhibition. Le Merle perché (2006/2008) depicts an alert life-size blackbird (François-Xavier’s handiwork) roosting atop a vertical branch (Claude’s contribution), both in black patinated bronze. When the cast is closely examined, one discerns a strand of rope knotted around the girth of the bough, a humble token of Les Lalanne’s union. Shortly before realizing this sculpture, François-Xavier had commandeered a cast of the same branch, albeit a few inches longer, and integrated it into L’Oiseleur (2004), his personal musing on the weather vane. Its avian-inflected title translates as “bird-catcher.” Although Claude did not cosign this particular work, it evinces the fluidity and permeability of the couple’s creative conversations. From the mid-1960s onward, birds, large and small, were a recurrent theme in François-Xavier’s oeuvre, as evidenced by Double Tourterelle, Oie sauvage (2002), Théière canard (2003), and Oiseau de Peter branché (grand) (Modèle de montage) (2004). In 2000, François-Xavier summarized Claude’s working method in terms that encapsulate the collaborative spirit at the origin of Le Merle perché: “Claude works as the birds sing, without really thinking about it[.] Imagine, if you will, a sort of conversation in which the other interlocutor is a bronze branch more or less from the garden next door. However unusual such a dialogue may seem, it’s nonetheless completely natural, even familiar.”[90]

For Singe aux nénuphars (2008/2010), Les Lalanne combined two disparate motifs that they individually had treated in the past: a monkey and plant appendages. François-Xavier provided the primate, based on his plaster model Singe attablé (2002), while Claude furnished the leaves.[91] From the object’s title, which translates as Monkey with Water Lilies, one presumes—precisely as critics, curators, and scholars have hitherto done—that this botanical element derives from the same flowering aquatic herb that Claude Monet had made famous and that François-Xavier had employed at various instances beginning in 1969.[92] In actual fact, Claude openly purloined the magnificent foliage from a type of Farfugium japonicum, commonly known as the leopard or tractor-seat plant due to its often variegated and distinctly shaped leaves, the perimeters of which may also be studded with teeth, as is the case in Singe aux nénuphars. Native to Japan, this flowering plant is rhizomatous, like the water lily, and thrives along streambanks and in humid meadows. Claude first incorporated the leafage into her work in 2000, designating its source as the nénuphar (water lily).[93] Although the artist had a knowledge of botany, it remains unclear whether she deliberately or unwittingly misidentified the plant. In Singe aux nénuphars, Claude arranged five leopard-plant leaves in an overlapping circular pattern to form the tabletop. With its knees bent, feet positioned sole-to-sole, and toes crossed, the seated monkey clutches the round structure over its head like an atlas or a caryatid. A great ape strikes practically the same pose in François-Xavier’s Gorille consolé (2002/2016). In the context of Singe aux nénuphars, one can understand the interlocking toes of the monkey as emblematic of Les Lalanne’s artistic partnership, not to mention the coupling of the plant and animal kingdoms. Les Lalanne further elaborated this duality by executing Singe aux nénuphars in two editions (bronze and aluminum) and in two versions (A and B), in which the primate cocks its head either to the left or to the right.[94]

In contrast to Le Merle perché and Singe aux nénuphars, both realized in the last years of François-Xavier’s life, Le Grand Centaure (1985) was the first monumental sculpture that Les Lalanne conceived together. The French architect Paul Chemetov, who had known the couple since the early 1960s, commissioned the piece to embellish the French embassy in New Delhi, which he and his colleague Borja Huidobro had designed and which was erected between 1983 and 1985.[95] As its title indicates, the sculpture portrays a centaur. Half-man and half-horse, this wild zoomorphic creature from Greek mythology, notorious for its barbarity and lustfulness, is the cousin of the zoophyte and a Western counterpart to those Hindu deities possessing both human and animal characteristics. The centaur’s composite morphology also underscores the collaborative practice from which it emanated. Chemetov and Huidobro cultivated the same sort of alliance when constructing the venue for which Les Lalanne’s sculpture was destined. While François-Xavier contributed the equine body, Claude was responsible for the arms and torso. To fashion the latter, she recruited the two architects to serve as models, as Huidobro recounted: “Half of the centaur’s torso is mine, the other half is Chemetov’s. We had to withstand the ordeal of having plaster moulds made directly on our bodies, which were then used to produce the bronze statue.”[96] The prominent vertical fissure bisecting the front and back of the centaur’s hollow trunk and the thin band that girdles the two sections symbolize this dual origin. That said, the idealized and symmetrical proportions of both halves of the cuirass-like torso call to mind ancient Greek notions of masculinity, suggesting that Claude only loosely patterned it on the actual physiques of her two middle-aged male muses.

Unlike the frenzied and pugnacious centaurs that populate Greek art, Les Lalanne’s poised personage stands with its left arm leaning on a mammoth drafting compass and delicately clenches a plumb line between the thumb and index finger of its right hand. The latter is an archaic instrument used in building construction to establish verticality by way of a weight (plumb bob) suspended from a string. The drafting compass and plumb line also happen to be the tools of architecture, Chemetov’s and Huidobro’s métier and a discipline with which Les Lalanne had familiarized themselves in their youth. In the early 1950s, Claude had studied architecture at the École des beaux-arts in Paris, and François-Xavier worked as a colorist and draftsman in the architectural studio of André Sive, where Claude’s first husband, Jean Kling, also was employed.[97] In Centaure (moyen) (1995/2008), a later and smaller bronze variation of Le Grand Centaure, the artists substituted the enormous drafting compass for a rigid, straightedged slat incised with a vertical interconnecting series of digits, ranging from one to nine. This device conjures not only a measuring rod, but also geometry, the branch of mathematics at the core of architectural design. In both versions of Les Lalanne’s sculpture, the centaur dons a helmet shaped like the shell of a giant snail or nautilus. Protecting the creature’s head and, by extension, its brain, the casque also largely obscures its face and, therefore, occludes its vision, another reference to the conceptual, cerebral foundations of both architecture and geometry as opposed to the predominately perceptual aspect of art making.

In the wake of François-Xavier’s death in 2008, his brother Jean-Philippe, who had regularly photographed Les Lalanne and their work beginning in the early 1950s, recognized the seminal role that his sister-in-law played in the relationship: “It was always Claude who encouraged François, who pushed him along, it was always her who put in all the carburant, provided the fuel. . . . Without her they would never have made so much work or had such success, my brother never had the same drive or stamina. . . . François was far slower, perhaps lazier even, he never had the same audace.”[98] The determination that drove Claude never ebbed, even during her final years. Concomitant with her private maneuvers to foster their collective creative venture, François-Xavier often served as their public voice, habitually seducing interlocutors with his puns and bons mots. This complicity not only reinforced their couple, but also ensured that neither artist was sidelined or left behind. “Art must be in life as life is in Art,” François-Xavier proclaimed in the mid-1970s.[99] Such an ethos of inclusiveness guided Les Lalanne throughout their long and prolific careers, enabling them to avoid the impasse of mettre dans une case. As they upended artistic boundaries and contravened art-historical conventions, they invented two distinct yet complimentary visual vocabularies in which reason never trumped fabulation. “Which is more certain, a mirage or reality?” François-Xavier pondered in his portfolio of prints aptly titled Polymorphoses (1978). “Nothing allows us to say that reality is anything other than a convincing illusion that endures.”[100] For over fifty years, Les Lalanne poetically tethered the real to the surreal in an abiding phantasmagoria, where familiar flora and fauna flourished alongside fanciful zoophytes, polymorphs, and other hybrid creations. In his first Manifeste du surréalisme (1924), André Breton trumpeted: “There are fairy tales to be written for adults, fairy tales still almost blue.”[101] A century after this declaration and six decades after Les Lalanne’s inaugural joint solo exhibition at the Galerie J, Les Lalanne: Zoophites renders homage to the many colorful and artful stories that Claude and François-Xavier Lalanne recounted in their remarkable oeuvres.

Known individually and collectively as Les Lalanne since 1966, Claude’s and François-Xavier’s artistic practices were deeply entangled. Their respective creative processes nonetheless remained recognizably distinct over their decades-long careers. Claude’s sculptures typically mimic the flora of her surroundings, such as a ginkgo leaf, a branch, or an apple. Having resuscitated the Renaissance art of casting forms from life, while also employing the more recent technique of electroplating, Claude achieved a delicacy and sensitivity in her work largely unparalleled in cast bronze. By contrast, François-Xavier is renowned for his life-size sculptures of animals, a practice inspired in part by his time working as a guard in the Egyptian and Assyrian galleries of the Musée du Louvre in Paris. With much time to study the massive Apis Bull, François-Xavier would later acknowledge that “the animal world offers an infinite repertory of forms connected to a universal symbolism” that “children as well as adults are sensitive to.” François-Xavier’s oeuvre demonstrates his commitment to the artistic tradition of zoomorphism through a Surrealist aesthetic, often making creatures that recall the dreamworlds of Lewis Carroll.

Based in Paris and Céret, in the south of France, Paul B. Franklin is an American art historian and a leading expert on the life and work of Marcel Duchamp. From 2000 to 2016, he was editor in chief of the scholarly journal Étant donné Marcel Duchamp, one of the most highly regarded publications devoted to the artist and his oeuvre. In addition to lecturing and publishing widely on Duchamp, he worked for numerous years with Jacqueline Matisse Monnier—the artist’s stepdaughter and a close friend of Claude and François Xavier Lalanne—assisting with the management of Duchamp’s estate. Since the late 2010s, Franklin has devoted his time to curating exhibitions, including Brancusi & Duchamp: The Art of Dialogue (2018) at Kasmin in New York, Matisse in Black and White (2020), also at Kasmin, and Please Touch: Marcel Duchamp and the Fetish (2021–22), which opened at Thaddaeus Ropac in London and subsequently traveled to its Paris location. His latest curatorial project, Marcel Duchamp and the Lure of the Copy, recently was on view at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice. In 2019, Franklin was elected to the Swedish Royal Academy of Fine Arts.

[1] François Pluchart, “De Raysse à Lalanne, Alexandre Iolas répond aux interrogations de la sensibilité actuelle,” Combat, 31 October 1966, 7. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are my own.

[2] O. H. [Otto Hahn], “L’Inventaire des Lalanne,” L’Express, no. 1249 (16–22 June 1975): 28. Hahn’s article is a review of the artists’ first retrospective, Les Lalanne (5 June–13 July 1975), which was initially staged at the Centre national d’art contemporain in Paris and subsequently traveled to the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen (1 August–15 September) in Rotterdam.

[3] Kathleen M. Morris, Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne: Nature Transformed (Williamstown, MA: Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute, 2021), 51.

[4] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Éric Jansen, “L’Œuvre poétique de Claude et François-Xavier Lalanne,” Point de vue, no. 2588 (25 February–3 March 1998): 42.

[5] Claude Lalanne, quoted in Alain Elkann, “Claude Lalanne,” interview conducted 19 February 2017, Paris (accessed 9 February 2023).

[6] See Daniel Abadie, Lalanne(s), trans. Deke Dusinberre (Paris: Flammarion, 2008); Daniel Marchesseau, The Lalannes, trans. Igor Agisheff (Paris: Flammarion, 1998); Robert Rosenblum, Les Lalanne (Geneva: Éditions d’art Albert Skira, 1991); and John Russell, “The Lalannes . . .,” in Les Lalanne (Paris: Centre national d’art et de culture Georges Pompidou, Musée national d’art moderne, 1975), 19–23. In the past few years, major auction houses, like Christie’s and Sotheby’s, have sporadically offered Les Lalanne’s work in evening sales of twentieth- and twenty-first-century art, rather than in those earmarked for decorative arts and design. Although this practice remains exceptional, a significant evolution occurred on 20 October 2023 at Christie’s in Paris, where François-Xavier’s iconic Rhinocrétaire I (1964) was auctioned in a single-lot evening sale (no. 22610) as part of a week of offerings of twentieth- and twenty-first-century art. With an estimate of €4,000,000 to €6,000,000, the sculpture realized €18,335,000, an auction record for the artist.

[7] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Gloria Emerson, “‘They Are Not Furniture,’ He Said, Sitting on a Sheep,” New York Times, 12 October 1966, 46.

[8] François Nourissier, Les Lalannes (Paris: Galerie Alexandre Iolas, 1966), n.p. I have translated this excerpt from the original French because the English translation included in the catalogue is wanting.

[9] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Jean Sprain Wilson, “Sheep Won’t Stay Down on the Farm,” Daily Home News (New Brunswick, NJ), 12 May 1967, 19.

[10] Claude Lalanne, quoted in Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne (n.p.: Reed Krakoff, Paul Kasmin, and Ben Brown, 2006), 8.

[11] Claude Lalanne, quoted in Les Lalanne: Fifty Years of Work, 1964–2015, ed. Adrian Dannatt (New York: Paul Kasmin Gallery, 2015), 158; and Adrian Dannatt, François-Xavier & Claude Lalanne: In the Domain of Dreams (New York: Rizzoli, 2018), 267. I have transcribed this quotation as it appears in the latter source, where the grammar and punctuation of the translation of the original French are slightly better.

[12] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne (2006), 9.

[13] Claude Lalanne, quoted in Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne (2006), 9.

[14] Claes Oldenburg, untitled text, in Environments, Situations, Spaces (New York: Martha Jackson Gallery and David Anderson Gallery, 1961), n.p. A typescript of the artist’s statement, which is dated May 1961, is in the Ellen Hulda Johnson Papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC.

[15] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Jansen, “L’Œuvre poétique,” 40.

[16] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Marchesseau, The Lalannes, 40.

[17] Claude Lalanne, quoted in Elkann, “Claude Lalanne,” https://www.alainelkanninterviews.com/claude-lalanne/#.

[18] François[-Xavier] Lalanne, “Questions,” in Artiste/Artisan? (Paris: Musée des arts décoratifs, 1977), 105.

[19] William Morris, “Preface,” in John Ruskin, The Nature of Gothic: A Chapter of The Stones of Venice(London and Orpington: George Allen, 1892), i.

[20] Marcel Duchamp, quoted in Pierre Cabanne, Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp, trans. Ron Padgett (New York: Viking Press, 1971), 16.

[21] Marcel Duchamp to Michel Tapié, 31 December 1949, collection David Fleiss, Paris.

[22] When Claude and François-Xavier wed on 6 February 1962, they brought to their couple children from previous marriages. She was the mother of three daughters (Caroline, Marie, and Valérie), and he was the father of one (Dorothée).

[23] This proverb is widely attributed to Poussin in French dictionaries and dictionaries of quotations, although its precise source remains elusive. On François-Xavier’s admiration for Poussin, see Dannatt, François-Xavier & Claude Lalanne, 207; and Les Lalanne: Fifty Years of Work, 158. In summer 1978, the Maison du Lot-et-Garonne in Paris hosted Hommage à Poussin (7–30 June), an exhibition of François-Xavier’s drawings inspired by the forefather of French classicism. In several scholarly publications, Pierre Rosenberg, president and director of the Musée du Louvre from 1994 to 2001 and a renowned Poussin specialist, referenced or reproduced François-Xavier’s drawings and prints based on works by Poussin. See, for example, Pierre Rosenberg and Louis-Antoine Prat, Nicolas Poussin, 1594–1665 (Paris: Réunion des musées nationaux, 1994), 178, 194, and 382; and Pierre Rosenberg, Nicolas Poussin: les tableaux du Louvre: catalogue raisonné (Paris: Musée du Louvre and Somogy éditions d’art, 2015), 69, 83, 91, 159, 225, and 247. Also see, Copier créer: de Turner à Picasso: 300 œuvres inspirées par les maîtres du Louvre (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1993), 168 and 190.

[24] Abadie, Lalanne(s), 297.

[25] Marchesseau, The Lalannes, 23; and Morris, Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne, 20. For an early nonscientific usage of the French term zoophyte, see François Rabelais’s novel Tiers liure des faictz et dictz Heroïques du noble Pantagruel (Paris: Chrétien Wechel, 1546), 67.

[26] Scholars, curators, and art aficionados habitually but erroneously maintain that Goldschmidt-Rothschild and Restany were married during the years that the former operated the Galerie J. In fact, the couple did not wed until 17 December 1966, around the time that she closed the exhibition space.

[27] From January 1916 until summer 1927, Brancusi had occupied a studio across the alley at 8 impasse Ronsin. During July 1927, the space suffered irreparable structural damage during a severe storm, and he was forced to abandon the property. Since 1 July 1926, Marcel Duchamp had been renting a studio at 11 impasse Ronsin, which he used as a storage facility and showroom for his allotment of Brancusi sculptures purchased from the estate of John Quinn. Duchamp transferred the lease to Brancusi on 1 January 1928 but continued intermittently to pay both the electricity and rent until 13 November 1929 and 1 January 1930, respectively. See Paul B. Franklin, Brancusi & Duchamp: The Art of Dialogue (New York: Kasmin, 2018), 158.

[28] For Les Lalanne’s memories of Brancusi, see Friedrich Teja Bach, Constantin Brancusi: Metamorphosen plastischer Form (Cologne: DuMont Literatur und Kunst Verlag, 2004), 263–65; Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne (2006), 8; Dannatt, François-Xavier & Claude Lalanne, 53; and Elkann, “Claude Lalanne”

[29] See Impasse Ronsin: Murder, Love, and Art in the Heart of Paris (Basel: Museum Tinguely; Heidelberg: Kehrer Verlag, 2020); and Impasse Ronsin, ed. Adrian Dannatt (New York: Paul Kasmin Gallery, 2016).

[30] William N. Copley, “Brancussi [sic], Buddy of Writer—Almost,” Evening Vanguard (Venice, CA), 12 May 1952, 12. I am grateful to Anthony Atlas for his assistance in locating this reference.

[31] François-Xavier cited 1962 as the year in which Metcalf presented him and Claude to Goldschmidt-Rothschild. See Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne (2006), 8. On Metcalf’s relationship with Goldschmidt-Rothschild, see Impasse Ronsin: Murder, Love, and Art, 114.

[32] Dannatt, François-Xavier & Claude Lalanne, 59.

[33] The copper-electroplated sculptures in question include, among others, Not a Shoe (1950), Objet-dard (Dart-Object, 1951), and Coin de chasteté (Wedge of Chastity, 1954). On their fabrication and composition, see Michael R. Taylor, Marcel Duchamp: “Étant donnés” (Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2009), 79–81 and 230–39.

[34] Claude Lalanne, quoted in Dannatt, François-Xavier & Claude Lalanne, 59–60.

[35] François Xavier et Claude Lalanne: objets (Paris: Galerie J, 1964), n.p. The title Zoophites does not appear in the exhibition catalogue, suggesting that François-Xavier happened upon it after the publication had been dispatched to the printer.

[36] Claude Lalanne, “Propos de Claude Lalanne,” in “Les Lalanne: les silhouettes et les phagocytes,” special issue, Aura: cahiers d’Artcurial, no. 1 (April 1991): n.p.

[37] James Metcalf, untitled text, in François Xavier et Claude Lalanne: objets, n.p.

[38] John Ashbery, “Segui Shows Horrors in Double Paris Show,” New York Herald Tribune (European edition), 6 October 1964, 5.

[39] For a series of photographs of François-Xavier working on Rhinocrétaire I in his studio, see Abadie, Lalanne(s), 300–1.

[40] Based on his restoration of Rhinocrétaire I prior to it being auctioned at Christie’s in Paris on 20 October 2023 (see note 6), Darius Metcalf generously outlined for me the physical relationship between the rhinoceros horn and its brass replica. In conformity with French law banning trade in rhinoceros horns, the original and the copy were separated in advance of the auction, and the sculpture was sold only with the brass version. The previous owner retained possession of the original horn.

[41] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Marchesseau, The Lalannes, 23.

[42] Claude Lalanne, quoted in Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne: fragments (Lausanne: Éditions Acatos, 2000), 7.

[43] Constantin Brancusi, quoted in Claire Gilles Guilbert, “Propos de Brancusi (1876–1957),” Prisme des arts: revue internationale d’art contemporain, no. 12 ([June] 1957): 6.

[44] François-Xavier Lalanne, “Propos de François-Xavier Lalanne,” in “Les Lalanne: les silhouettes et les phagocytes,” special issue, Aura: cahiers d’Artcurial, no. 1 (April 1991): n.p.

[45] The Sultan of Cambay had presented the rhinoceros to Afonso de Albuquerque, governor of Portuguese India. The latter, in turn, decided to send it to Manuel I, who kept a menagerie in Lisbon. Off the Italian coast near Porto Venere, however, the ship transporting the rhinoceros capsized during a storm, and the animal perished before reaching the Vatican. See Silvio A. Bedini, The Pope’s Elephant (Nashville, TN: J. S. Sanders & Company, 1998), 112–32.

[46] Bedini, The Pope’s Elephant, 119–24.

[47] On the history of Clara and her phenomenal impact on European culture, see Charissa Bremer-David, “‘Animal Lovers Are Informed,’” in Oudry’s Painted Menagerie: Portraits of Exotic Animals in Eighteenth-Century Europe, ed. Mary Morton (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2007), 91–103; and Glynis Ridley, Clara’s Grand Tour: Travels with a Rhinoceros in Eighteenth-Century Europe (London: Atlantic Books, 2004).

[48] Oudry’s Painted Menagerie, 143; and Ridley, Clara’s Grand Tour, 161.

[49] Beginning in the early 1950s, the rhinoceros and its phallic horn, as well as Dürer’s woodcut, obsessed Dalí, as evidenced by the following non-exhaustive list of works: Rhinocéros en désintégration (Disintegrating Rhinoceros, 1950), Figure rhinocérontique de l’Illisus de Phidias (Rhinocerontic Figure of Illisus of Phidias, 1954), Étude paranoïaque-critique de “La Dentellière” de Vermeer (Paranoiac-Critical Study of Vermeer’s “The Lacemaker”, 1955), Rhinocéros habillé en dentelles (Rhinoceros Dressed in Lace, conceived 1956 and issued in multiple bronze editions), Rhinocéros cosmique (Cosmic Rhinoceros, conceived 1956 and issued in multiple bronze editions), and Chevauchée céleste (Celestial Ride, 1957). In Loss of the Lisbon Rhinoceros (2008), Walton Ford revisited the tragic demise in early 1516 of the rhinoceros that Manuel I of Portugal had sent to Pope Leo X (see note 45). On Dalí’s rhinoceros-inspired production, see Robert and Nicolas Descharnes, Dalí: le dur et le mou: sortilège et magie des formes: sculptures et objets ([Azay-le-Rideau]: Eccart, 2003), 56–71.

[50] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Marchesseau, The Lalannes, 30.

[51] “Le Prix de l’Académie Julian,” Arts: beaux-arts, littérature, spectacles, no. 174 (9 July 1948): 5; and “Deux Prix de peinture,” Arts: beaux-arts, littérature, spectacles, no. 222 (8 July 1949): 5. François-Xavier’s winning entries, as well as several other early artworks realized during or immediately following his time at the Académie Julian, were recently featured in the exhibition Un phare pour l’art: l’Académie Julian à Honfleur (1949–1957) (2 July–7 November 2022) at the Musée Eugène Boudin in Honfleur. On the artist’s time at the Académie Julian and his two awards and for reproductions of his early artworks, see the eponymous catalogue, Un phare pour l’art: l’Académie Julian à Honfleur (1949–1957) (Honfleur: Société des amis du Musée Eugène Boudin, 2022), 20, 23n21, 38, 41–43, 59–61, 78–81, 96–97, 103–9.

[52] R. V. [Robert Vrinat], “Le Prix de l’Académie Jullian [sic],” Arts: beaux-arts, littérature, spectacles, no. 176 (23 July 1948): 4.

[53] Claude Lalanne, “Propos de Claude Lalanne,” n.p.

[54] Claude Lalanne, quoted in Jérôme Peignot, “Lalanne,” Connaissance des arts, no. 176 (October 1966): 122.

[55] André Breton, “La Beauté sera convulsive,” Minotaure, no. 5 (12 May 1934): 12.

[56] Rosalind E. Krauss, The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1986), 97; and Comte de Lautréamont [Isidore Ducasse], Les Chants de Maldoror (Paris: n.p., 1869), 290.

[57] Ashbery, “Segui Shows Horrors in Double Paris Show,” 5. A photograph of either Choupatte I or Choupatte II was reproduced in the catalogue of Zoophites.

[58] Choupatte also recalls several colloquial French terms of endearment, including the adjective and noun chou, which translate as “sweet” and “darling,” respectively, and its masculine and feminine nominal diminutives chouchou(te), choupinet(te), and choupette, all of which also signify “darling.”

[59] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Marchesseau, The Lalannes, 32.

[60] See Impressionist & Modern Art Day Sale (London: Sotheby’s, 25 June 2002), 126, lot 198; and 20/21 Century London Evening Sale (London: Christie’s, 7 March 2024), 208–9, lot 104.

[61] “Claude Lalanne’s Sculptures,” The Paris Review, no. 49 (summer 1970): 168.

[62] Claude Lalanne recounted the conversation with Yves Saint Laurent that inspired her to undertake Homme à la tête de chou in Claude de Leusse, “Sculpting Fashion,” Women’s Wear Daily, 26 September 1969, 5. Both Homme à la tête de chou and Caroline enceinte bear a striking resemblance to several of Dalí’s drawings and paintings of women and men with floral bouquets for heads. These include, among others, Femme à tête de roses (Woman with Head of Roses, 1935), Three Young Surrealist Women Holding in Their Arms the Skins of an Orchestra (1936), Necrophilic Spring (1936), Dreams Puts Her Hand on a Man’s Shoulder (1936), Man with Head of Blue Hortensias (1936), and Untitled (Woman with Flower Head) (1937).

[63] Marchesseau, The Lalannes, 33.

[64] See Alain Beausire, “Le Marcottage,” in La Sculpture française au XIXe siècle (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1986), 95–106; and Nicole Barbier, “Assemblages de Rodin,” in Le Corps en morceaux (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1990), 241–51.

[65] Claude discussed the realization of the sculpture and Iolas’s negative reaction to it in an interview published in Alexander the Great: The Iolas Gallery, 1955–1987 (New York: Paul Kasmin Gallery, 2014), 62.

[66] Claude Lalanne, “Propos de Claude Lalanne,” n.p.

[67] Claude Lalanne, “Propos de Claude Lalanne,” n.p. The artist frequently but erroneously stated that she culled these stems from Heracleum sibiricum, known in French as berce de Sibérie (Siberian hogweed). This edible variety of hogweed is far more modestly proportioned than its colossal counterpart. Caroline Hamisky Lalanne kindly shared with me her memories of the giant hogweed that grew around her parents’ home-studio in Ury and the severe cutaneous effects that resulted if its sap touched the skin. For a photograph of Claude taken around 1985, which shows her in her garden surrounded by stalks of giant hogweed, see Marchesseau, Les Lalannes, 11.

[68] Les Lalanne: Fifty Years of Work, 120. Kathleen M. Morris incorrectly claimed that Claude first incorporated the ginkgo leaf into her oeuvre in the mid-1990s. The artist’s bronze Trône de Pauline, which features the same combination of outsized ginkgo leaves and giant hogweed stems as in Les Berces adossées, dates to 1990 and was exhibited from June to November 1991 as part of a retrospective of Les Lalanne’s work at the Château de Chenonceau in the Loire Valley. Trône de Pauline also was reproduced in the accompanying catalogue. See Morris, Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne, 105; and Rosenblum, Les Lalanne, 81 and 139.

[69] On the ginkgo tree, its botanical uniqueness, and cultural significance, see Peter Crane, Ginkgo: The Tree That Time Forgot (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2013).

[70] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Selected Poetry, trans. David Luke (London: Libris, 1999), 165.

[71] The fused feathered twosome in Double Tourterelle is not dissimilar from the pairs of indistinguishable, interlaced human figures that Brancusi chiseled directly from single blocks of stone in the numerous iterations of his celebrated sculpture Le Baiser (The Kiss, 1907–45).

[72] “Claude Lalanne’s Sculptures,” 157–68.

[73] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Marchesseau, The Lalannes, 41.

[74] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Emerson, “‘They Are Not Furniture,’” 46.

[75] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Abadie, Lalanne(s), 350.

[76] François-Xavier Lalanne, quoted in Claude de Leusse, “The Fashions: Nice Monsters and Gold Fingers,” Women’s Wear Daily, 8 January 1968, 14. This article was republished in the Chicago Tribune, 22 January 1968, sect. 2, 5.

[77] The caption accompanying the photograph of Grand Chat polymorphe in Women’s Wear Daily was transposed with that of François-Xavier’s Lapin à vent (1969), a weather vane in the form of a winged rabbit.

[78] Abadie, Lalanne(s), 295.

[79] Abadie, Lalanne(s), 295; John Russell, “The Lalannes . . .,” 21; and Les Lalanne: Fifty Years of Work, 158.

[80] Claude Lalanne, quoted in Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne: fragments, 7.

[81] Marchesseau, The Lalannes, 50. The English translator of Marchesseau’s book overlooked the phrase “un soir de lune à minuit” (a moonlit night at midnight), which appears in the original French. See Daniel Marchesseau, Les Lalanne (Paris: Flammarion, 1998), 50.

[82] Important Design (New York: Sotheby’s, 13 December 2017), 80.

[83] Claude Lalanne, “Propos de Claude Lalanne,” n.p. Without citing a source, Kathleen M. Morris relayed a more detailed version of this story: “In 1972 Claude was given a small stuffed crocodile by a staff member of the Jardin des Plantes in Paris.” See Morris, Claude & François-Xavier Lalanne, 84.