On occasional Saturday mornings, Kasmin shares essays and interviews that expand critically on the work and practice of gallery artists. The below conversation between Roxy Paine (b. 1966) and curator Michael Goodson is featured in the monograph Roxy Paine: The Dioramas, published by Skira in 2021. The artist's exhibition at Kasmin, Normal Fault, was on view at 509 West 27th Street from November 4–December 23, 2021. Explore the works in our online viewing room.

Michael Goodson: You have a lifelong interest in science—in geology and mycology, for example. In your work from the 1990s and 2000s, this interest took the form of an exploration of systems. But you also seem interested in pushing beyond the empirical boundaries of science. What is that about for you?

Roxy Paine: I’m ambivalent about the word “science.” I’m interested in looking at the different lenses through which we view nature and natural systems, and how human behavior and history fit within those systems.

MG The systems that you’ve explored are implicitly about human behavior and the way the mind works.

RP I think about human behavior and how we interact with the natural world, how we alter it and are altered by it, and how we seek to control nature and the eco-system. You can look at science as a series of absolutes, as trying to find the keys to nature and understanding the laws that govern things in a comprehensive way. I’m completely against finding keys. I’m not interested in keys whatsoever. I’m interested in the uncertainty, in not trying to resolve it. There’s a fair amount of ambiguity in all this. And melancholy.

MG I’m curious about your personal history with dioramas. What was your first encounter with them and is this body of work in any way related to that?

RP I visited Holland as a kid. There was a beautiful and elaborate panorama in a building close to the beach, and what was interesting was that the panorama recreated a scene of the nearby shore. Why build a replica of a site that’s just a quarter-mile down the road? This panorama was a very different kind of displacement than the ones you see at the Museum of Natural History, for instance, which often depict places and scenes that are far away in space and time. There was a surreal banality about it, and I guess the questions that it aroused stuck with me for the next thirty years.

MG Do the dioramas at the Museum of Natural History achieve, in your estimation, an unhindered view of a place or the cumulative idea of a place?

RP Those dioramas go back to the 1890s, when the museum first opened, and crystallized a moment that was actually in the process of being destroyed. I responded to them more on an emotional level than an intellectual one, especially the dioramas of the American West. They had a powerful emotional impact on me because I realized they marked the beginning of its end. The railroads were coming through and changing that whole region by bringing in European settlers who were fundamentally altering the landscape. They have an intrinsic tragic quality that is …

MG … about the erasure of what they were providing a view into?

RP Yes.

MG Do you feel that your Dioramas are doing the same thing?

RP Perhaps. We don’t know how things will unfold in the next decades. But it brings up one of the raw ingredients in these works—the language of time. My Dioramas are a vision of the present imagined from sometime in the future utilizing a methodology from the past. I feel the sense of time they create is nebulous, uneasy, and ultimately unstable.

MG I see that very clearly in them.

“I think about human behavior and how we interact with the natural world, how we alter it and are altered by it, and how we seek to control nature and the eco-system.”

RP The habitat diorama, which traditionally depicts idealized landscapes of nature, can be understood as a particular type of lens that shapes our perception and our knowledge of the world. But it can also be applied to aspects of human nature and human existence. I’m interested in how taking this supposedly objective genre of display and turning it back upon ourselves produces disconcerting results. We tend to see our built environment as a manifestation of our sophistication and modernity, but it is also embedded in how our genus has evolved over the last three million years—and, consequently, in our animality. It exists because of certain internal, primitive aspects of our makeup. To me, my Dioramas are a way to highlight and reveal this prehistoric aspect of our everyday worlds, our brains, and our motivations. They’re a series of questions and investigations rather than answers.

MG I’m curious about how the melancholy you see in traditional natural history dioramas gets transposed and translated in yours? What’s interesting is that, while your subject matter is emotionally charged, your Dioramas also act as screens that invite viewers to project their own ideas and emotions onto them.

RP I think that’s right. And the idea of how to create spaces that would accept our projections was something I grappled with, especially with the raw-wood Dioramas, “Carcass” (2013) and “Checkpoint” (2014). Blankness and the balance between generality and specificity was something I was interested in fine tuning in order to emphasize this idea of a screen that we project our emotions onto, so my decisions to use wood, what kind of wood with what kind of grain, which details to keep and which to emphasize—they were all important.

MG The familiarity and banality of the places you depict, for instance the fast-food restaurant in “Carcass,” and a generic office in “Meeting” (2016), invites us to feel confident that we know them. These are familiar places for most of us. But the way you render them really plays up what we don’t know about them. I’m thinking about the references to the brutality of fables that you’ve chosen to put on the dry erase boards in “Meeting.” And in “Checkpoint,” you depict what is normally a bustling space utterly congested with humanity as empty. We never really get to look at airport security checkpoints in this way, and the way you present it and tweak it really animates these spaces and enables them to project out toward the viewer.

RP Speaking to the idea of projection, for instance with “Bastard Octopus,” one of the decisions I made was to make it blank, to render it in white so it becomes, metaphorically speaking, a kind of satellite dish or radio receiver. Although the wood has a certain quality and texture in the grain that I’m playing with, I wanted to present a certain blankness that also defines these places because they’re designed to receive our projections.

MG The history of the tableau is about projecting an idea out, either to tell a story or put it into motion. But you present precious little in the way of narrative. Instead, your Dioramas feel like vessels for our psychic needs. Do you see them primarily as receptacles?

RP They have evolved over time. In “Meeting” I was trying to do something different than what I was doing in some of the earlier ones. It has text and, more specifically, both color and textured surfaces.

MG It’s comparatively baroque. But I think you can argue that it still serves as an empty vessel, which I think is really interesting. Maybe this is because of its shape and your use of forced perspective, which is present in some but not all of the Dioramas. It’s there in “Bastard Octopus” (2014), and “Checkpoint,” as well as in “Meeting” and “Experiment” (2015).

RP That’s right.

MG Every Diorama you made after you made the first two, “Carcass”and “Control Room,” in 2013, is a foray into manipulating the representation of space through perspective. That move is part of the history of the diorama.

RP One of its tropes is creating the perception of greater space than actually exists. In one sense, I’m investigating different aspects of how that’s possible. “Checkpoint” was the first one that really dealt with dramatic perspective-what I call “funneling.” It was partly because I see TSA checkpoints as funnels that supposedly filters out bad or dangerous elements of humanity. The most recent one, “Desolation Row” (2016), doesn’t use perspective at all; instead, it sets up a contrast between a middle ground and a distant ground to create a sense of space.

MG It takes us beyond the ocular and begins to feel wholly corporeal. Your whole body is involved even though it’s intended primarily for your eyes, so it feels like some sort of abattoir [slaughterhouse]. I think that’s because you’re depicting an architectural space that we move through and know with our bodies.

RP I don’t want these works to be seen as just playing tricks on the eye. They’re engaged with ideas of the diorama and how dioramas operate. But they’re also guided by a very practical concern, which is to show a space and have it exist physically as an object without taking up eighty feet. I don’t feel comfortable occupying that much space in a gallery or a museum. Artists aren’t supposed to talk about the practical considerations of their decisions, but these always play an important role.

MG So it’s also practical. But depicting eighty feet of space in eighteen is also subtly altering our consciousness.

RP It has to work both practically and conceptually. I don’t believe in employing a method for its own sake or for the sake of creating an impressive structure.

MG That’s been consistent throughout your work and career. There’s always a conflation of elements that manifest as something irrational or illogical. But that’s also part of your intention.

RP Creating a kernel of logic that’s true to itself, even if it departs from everyday norms and accepted realities—yes, I think that’s a big part of what I do.

MG There’s one aspect of the Dioramas that I think is universal to all your work: a persistent absence. I see it in the Machines and the Dendroids you started making in the late 1990s and 2000s. It’s a very effective and emotional part of your vocabulary. How deliberate is it?

RP It has always been a conscious decision.

MG Yet your works also manifest the presence of humanity at some point.

RP The presence of people, or their impact, is implied.

MG Even if that impact is neglect.

“There’s also a simpler, more personal dimension to my interest in nature and its systems. Before I came to New York I was very much an outdoors person. I did a lot of hiking, and I think the early nature pieces, which I made in industrial buildings in New York City, expressed my longing to be outdoors. I wasn’t amongst the mushrooms and I was longing for nature.”

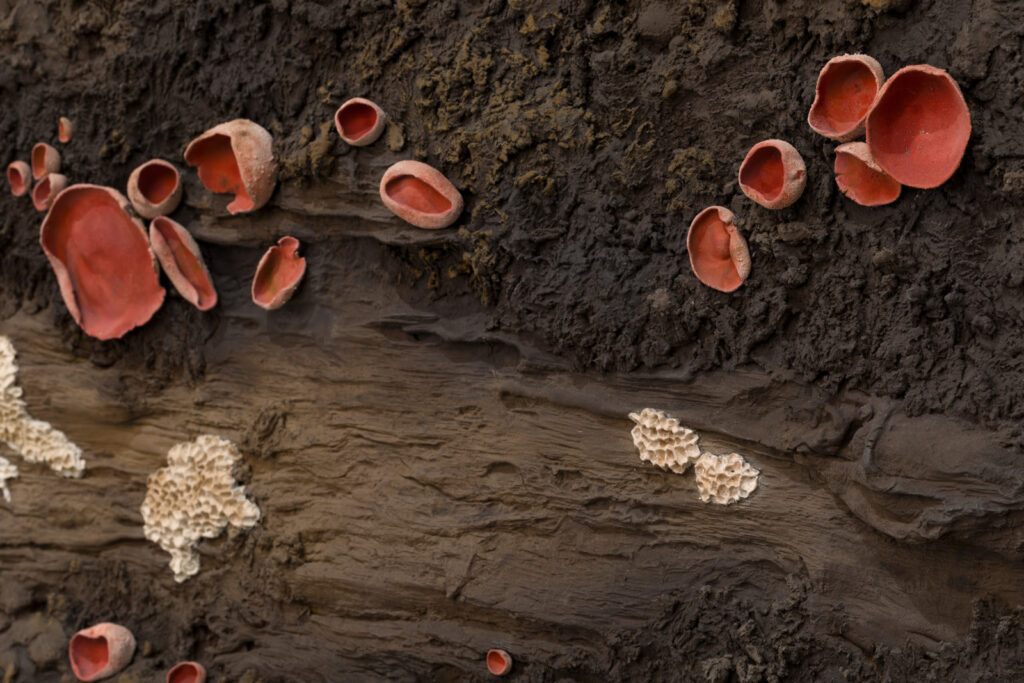

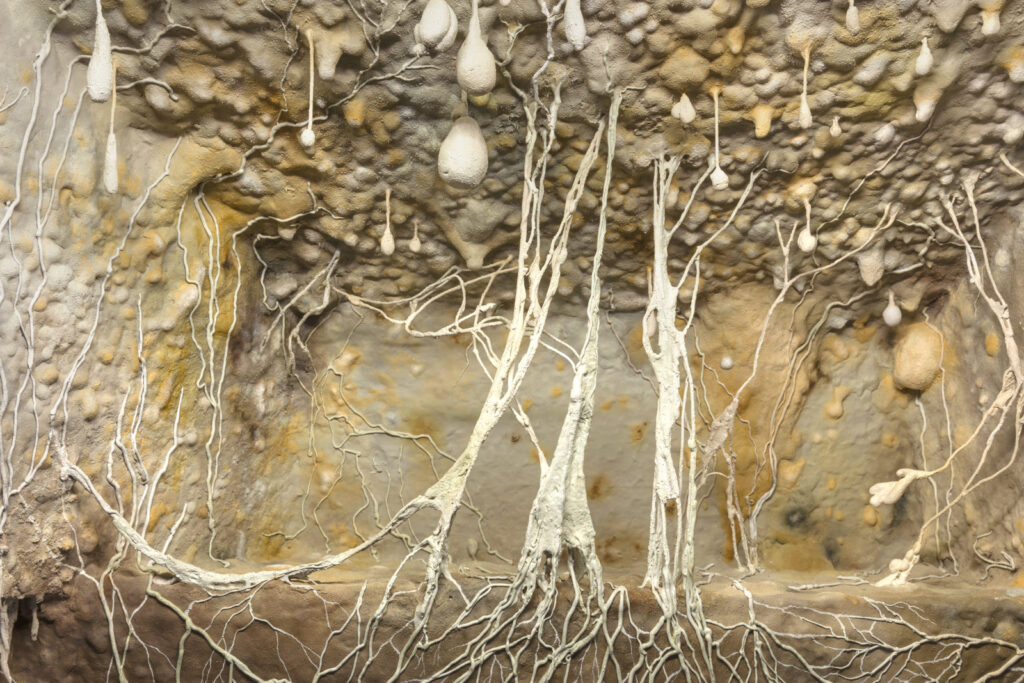

RP Yes, through their actions or lack of actions. For instance, in the various mushroom field works from the 1990s, the absence of humans or animals was a way to foreground what people consider to be secondary or unimportant. It’s a way of saying these plants and mushrooms are not just a background to an animal habitat. For example, I see the Dendroids as being about our distance from the world around us, about how we destroy everything we touch.

MG I’ve often thought about your use of rules and limits in the Dendroid sculptures. People call them trees and see them as romantic works that glorify the idea of the tree. In reality, they’re about a system stripped bare of its ornaments, whether it’s a tree or a neurological structure.

RP You’re not wrong. There’s also a simpler, more personal dimension to my interest in nature and its systems. Before I came to New York I was very much an outdoors person. I did a lot of hiking, and I think the early nature pieces, which I made in industrial buildings in New York City, expressed my longing to be outdoors. I wasn’t amongst the mushrooms and I was longing for nature. Generally speaking, all of my ideas come out of intense depression.

MG Is the massive amount of labor you put into each of your pieces related to that?

RP Definitely. It’s the way I’ve always self-medicated. Setting up projects or goals that require a great amount of work creates a space where depression doesn’t have as much of a hold on you.

MG There are moments in which the Dendroids explore connectivity, too.

RP Yes, for example, “Maelstrom” (2009) is about connection, but also about destruction.

MG The violence of “Maelstrom”is undeniable. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I don’t think you’ve ever made something celebratory. That’s just not part of your vocabulary.

RP That’s true. But there’s some solace in meditating intensely on something, even if it’s something bleak.

MG I’m much more apt to believe in solace than in celebration. Celebration is folly.

RP Maybe solace is the most we can hope for. (laughs)

MG Is that related to the exploration of the abject in your work? There are obvious tropes here associated with it. But in “Maelstrom” you seem to have struck a balance between the aspects that are about connectivity and those that are more entropic—and more chaotic—in their nature. I feel like that balance is struck in many of your works.

RP Yes, I always try to avoid the obvious tropes, for example, by taking the different bacteria that are decomposing something and trying to find the language of that decomposition. I was looking for a deeper connection. If you think about it, the term “decomposition” itself is inadequate. If we look at it from the perspectives of both the decomposing body and the bacteria simultaneously, we see two very different phenomena.

MG It’s interesting that your allegiance lies with the bacteria. Recently, I read about a new method of burial that dresses the corpse in a suit laced with mushroom spores. The body is decomposed very quickly. And that makes sense. A standard burial is bizarrely about preserving the body as long as possible, and cremation, if you think about it, is an inordinate waste of energy. The mushroom spore burial suit made me think of you.

RP It’s also about control. We’re trying to control what happens to our bodies after death. It denies the natural course of things. There isn’t anything more futile than that.

MG The vessel should rightly decompose.

RP I’d rather provide nutrients in my grave to other organisms than be in some encasement that blocks that from happening.

MG In a funny way, that thought describes the way your Dioramas offer an unflinching look at the truth of something that really takes into account, among other things, its emotional content. They’re not content to offer an abstract understanding of something that doesn’t implicate the viewer.

RP You’re bringing up an interesting point. The architectural dimension of the Dioramas seems to keep some people from engaging them emotionally. People are more able and willing to have an emotional response to something “natural” than something architectural.

MG What do you make of that?

RP I think it’s a learned habitual limitation. People have been trained—or train themselves—to have certain responses to certain things and not to others. One of my main goals is to open up the boundaries between different kinds of experience. I’ve always been interested in the fact that we need the comfort of categories, of placing things into discreet boxes, even when it really serves no purpose, or, in fact, hinders our perceptions. The Specimen Case works were very much about this aspect of our brain, the need to catalog, categorize, and compartmentalize. Of course, we do it for safety and security, to feel comfortable in the feeling that we know something. The Dioramas are a way for me to destabilize and open up these concrete delineations, to make them more permeable to other perceptions. Whether I’m successful at doing that is another question.

MG You’re exploring the way we think. I think the Dioramas are as much about collective consciousness as about individual consciousness.

RP At an airport security checkpoint, you’re part of a collective experience, but everyone is also completely lost in themselves. No one really converses. You’re with other people, but you really can’t interact with them, except in an official kind of way. If you joke about the wrong thing you can get arrested.

MG All the Dioramas seem to speak to this issue. They depict places where we’re forced to be together but are psychologically isolated. I think that experience is particularly acute in “Meeting,” which depicts a room in which an Alcoholics Anonymous or other kind of support group gathers: uncomfortable office chairs in a circle, a cistern of bad coffee with Styrofoam cups, a crappy drop ceiling with stained tiles. There’s something incredibly closed and isolating about these kinds of meetings. In fact, one of the tenets of AA is that nothing that’s said, things that are often deeply emotional, can ever leave that room.

RP It’s a limited collective experience. The rules prohibit sharing it with those who were not there.

MG What’s fascinating to me is that your Dioramas underscore the way these experiences are physical, the way we experience them through our bodies. At a security checkpoint at the airport, we’re herded together. We’re uncomfortable and very conscious of our bodies. We’re forced through little spaces and photographed in deeply intrusive ways.

RP You’re scanned and prodded, and you feel like you’re being stripped of your clothes. The earlier scanning machines were apparently graphic in that way. They’ve since made them more discreet.

MG So we’re told.

RP (laughs)

MG In “Carcass,” you seem to present us with our collective decision, one that’s arguably pathological, to be party to massive caloric intake.

RP Fast-food restaurants are highly optimized machines of caloric delivery. In contrast to most restaurants, which are as much about social experience and conversation as eating, about establishing and re-establishing emotional connections, there’s very little social interaction happening in fast-food restaurants. Making food and consuming it is reduced to the most efficient factory process.

MG The Dioramas feel like they bring together many ideas you’ve explored in the past.

RP In one way or another, I’ve been thinking about the Dioramas for more than twenty-five years. I was already thinking about them when I was making the various field works in the early 1990s.

MG Do you think of yourself, for lack of a better term, as a moralist?

RP I don’t think so. I associate being a moralist with control. Ultimately, it’s about the desire for some form of control over the universe and our world. I would say that I’m always grappling with being a moralist rather than actually being one.

MG Your work also takes the measure of the benefits of control, when, for example, it’s about feeding more people or curing illness.

RP I think so. Many horrible things have come out of good intentions. Think of genetically modified food. It’s true that there are corporations that want to monopolize technologies like that in order to make money. But it’s also true that technology will hopefully provide more food for the ever-growing global human population. I think of my work as political, but not in a black-and-white kind of way. It is trying to reveal complexity and operates in a gray zone. Historically, humans have done terrible things when they operate on the basis of absolutes.

MG Maybe this brings us back to the reticence you expressed in the beginning of our conversation about science. After all, science tends to be about absolutes. Historically, discovery has been penetrative and damaging. This is partly due to the fact that we don’t understand where we’ve arrived, and our penchant for control fouls the scenario before we understand what we’ve discovered.

RP It certainly can be the case. But I would say the scientific revolution was actually a repudiation of the absolutes that the Church had laid down. Up until that moment in history, it was the Church—or whatever religion you espoused-that dictated what was right, what was wrong, what you should be searching for, and what the answers were. You didn’t have to try and find your own answers. God had the answers. They were there in the book, or with the priest, the rabbi, or the imam.

MG That’s still going on.

RP That’s true. The scientific revolution was very radical in that it started with the assumption that we do not know, and because that’s the case, we’re going to look at things as they are and try and figure out what’s going on.

MG But I wonder if your work isn’t also pointing out the limits of empiricism and the danger of embracing it too completely. Empiricism comes with a kind of hopelessness. If there’s no god, and if all we have is the world we can know empirically, then we’re lost and hopeless.

RP Yes, but I find a certain hope in embracing hopelessness—a hope of the hopeless. There’s folly in religion, but there’s folly in fully embracing science, too, because science doesn’t help us answer larger moral questions.

MG You’re talking about a kind of impossible pursuit of balance. Your work often feels like it’s looking for something like that.

RP Maybe that’s what I mean when I talk about melancholy. To me, melancholy is very much about ambivalence, a state in which there’s no clear right and wrong, where things aren’t black and white. There’s a point where you can just accept that things are unresolved and imperfect.

MG Melancholy has the potential for clarity. It allows you to be somewhere in between belief and a skeptical, empirical relationship to the world.

RP It’s the position of the observer, the position of contemplation.

MG Is this where you see your work being situated?

RP That’s what I’ve always thought. The art that I’ve always found the most intriguing is always somehow contemplative. There’s often a thread of misanthropy in it, but being misanthropic doesn’t mean that you don’t find humanity fascinating.

Michael Goodson is the Curator and Director of Programs at The Contemporary Dayton. With over 20 years experience, Goodson has held positions as Senior Curator of Exhibitions at the Wexner Center for the Arts, Director and Curator of Exhibitions at the Columbus College of Art and Design’s Beeler Gallery, and as Director at James Cohan Gallery, NY. He has organized single artist exhibitions by Diana Al-Hadid, Charles Atlas, Leonardo Drew, Trenton Doyle Hancock, Jessica Jackson Hutchins, Donald Moffett, Carrie Moyer, Roxy Paine, Yinka Shonibare, Robert Smithson, and Fred Tomaselli, among many others.