On the occasion of Kasmin’s ongoing solo exhibition of rarely-seen geometric abstractions by the Abstract Expressionist pioneer Lee Krasner, Jason Drill explores a rarely-examined chapter of Krasner's career. Featuring previously unpublished visual material, the essay reveals this period to be a longer effort than is typically recognized. Reuniting paintings that survive from a time in which Krasner often destroyed or painted over her canvases to create new works, Lee Krasner: The Edge of Color, Geometric Abstractions 1948–53 remains on view at 509 West 27th Street, New York, through March 28, 2024. This essay appears in the accompanying catalogue, now available to order from Kasmin Books.

“A good many of the artists painting today, my contemporaries, seemingly came from one image…very unlike my own experience. I find myself working for a stretch of time somewhere between four and five years on something and a break will occur [in my] imagery and I have to go with it…”—Lee Krasner

Lee Krasner could not be pinned down. She worked resolutely for half a century, consistently reinventing her painterly style. She is best known for her monumental abstract paintings made with confident gestures and dazzling color palettes that come to life, but Krasner took pride in her ability to escape a singular image that would overly define her work. She resisted a tendency she identified among many of her contemporaries—to be typecast, stuck to one image, hindered by public expectations about how her paintings should look and, inevitably, a set of criteria by which they would be judged. For Pollock, it was the drip, a swash of line and color freed from the confines of form; for Newman, the zip, a vertical band extending from the upper to lower edges of the canvas; for Rothko, soft-edged rectangles made in thin washes of paint in variously expressive colorways. Krasner, for her part, routinely experienced what she called a “break” in her imagery, an inexplicable splintering of style that marked the birth of a new phase of her painting. These transitions defined Krasner’s working method over the course of her career, resulting in dramatic stylistic leaps between each of her painting series.

When Krasner broke from her intimately scaled “Little Images” in 1950, her patterns of heavily stroked, colorful impasto had begun to achieve an orderly structure, often resembling a set of geometric shapes housed in a grid. Working flat on a table or the floor in an upstairs bedroom of her home in Springs, New York, while her husband Jackson Pollock took the outdoor barn as his studio, Krasner’s artistic vocabulary had begun to emerge. But it was not until 1955 that she would achieve her first major critical and commercial success with the debut of her seminal collage paintings, made by recycling old works. In between the “Little Images” and the collage paintings lies a rarely-examined body of work, most of which the artist destroyed, that uncovers Krasner’s sustained interest in geometry as a tool of abstraction. Krasner would ultimately abandon this direction by the mid 1950s, only later reprising her interest in hard-edge geometric shapes in the 1970s, but a suite of paintings related to Krasner’s first-ever solo exhibition in 1951 reveals this interest to be a longer effort than is typically recognized. Created while working through experiments in automatic painting, managing Pollock’s flourishing career (not to mention his well-known struggle with alcoholism), and navigating the currents of contemporary criticism, Krasner’s geometric abstractions sow the seeds of several techniques and formal elements the artist would employ in her most defining paintings series of later decades.

In the early 1950s, Krasner focused her attention on geometric relationships culminating in fourteen paintings, each identified by number, that she exhibited at Betty Parsons Gallery in the fall of 1951. Krasner set to work through that summer, undoubtedly excited by the opportunity to present her paintings in her first solo exhibition. After years of being dismissed by her peers while Pollock’s artistic identity eclipsed her own, the exhibition finally affirmed Krasner’s standing as an artist in her own right. Yet only two of the fourteen paintings survive in their original states: Number 2 (1951) and Number 3 (1951); Krasner destroyed or painted over the rest. Photographs of two nonextant paintings from the show survive in the Archives of American Art, and the photographs confirm that Krasner repurposed a number of canvases as supports for new works, as is the case with Number 12 which became Milkweed in 1955. Others were cut, torn, and pasted as collage elements.

The largest painting Krasner had ever made to date, Number 2 reads like a panoramic vista of squares and rectangles in soft, glowing colors. Thin layers of diluted yellow, red, orange, and blue paint appear to blend into the canvas while successive scumbling modifies these colors into the muted tones present today. Horizontal rectangles counterpose long vertical bands that echo the forms seen in Number 3, which Krasner described as the first work in the series, realized in a similar palette of earth tones.[1] “It was a vertical-horizontal measurement of space in soft color,” Krasner once stated of Number 2.[2] Krasner tacked unstretched canvas against an entire wall of the bedroom to paint Number 2, which arguably represents her greatest commitment to exploring geometric relationships through modulated fields of color.[3] This body of work inaugurated a remarkable change of scale for Krasner, who began her “Little Images” in the same bedroom in 1946. In describing the genesis of works like Number 2 to art historian Dorothy Seckler, Krasner once stated, “It was in direct antithesis to this so-called image painting, in scale it went up to about that size…the paint was applied very thinly and it went into, in the roughest and crudest sense, a vertical and horizontal distribution…”[4] According to Krasner, the underpinning, almost grid-like structures of her paintings relate to the earlier series but “resolved themselves better in a larger scale.”[5] Scale would become an increasingly important element of Krasner’s paintings over the next several decades—as she would later remark, “Changing scale can be an important aspect of seeing what can be done with an idea.”[6]

Krasner apparently abandoned this geometric style of painting after her Betty Parsons exhibition, when her disappointment in the show’s lack of sales set the stage for her collage paintings. Still, Krasner saved Number 2 and Number 3, suggesting she hesitated to completely forget such an important personal and professional milestone. That Number 2 remained rolled until at least 1967 and went unseen for over seventy years after the Betty Parsons exhibition indicates its safekeeping in Krasner’s possession for the remainder of her life.[7] A suite of paintings of squares and rectangles, probably realized around the time of Number 2 and Number 3, further underscores Krasner’s reluctance to give up on this direction before her next break. Equilibrium (c. 1950–53), rendered in a similar palette as Number 2, features an arrangement of colorful rectangles of various sizes brushed in thin layers of paint. Splatters of brown and white paint, presumably the residue of a Pollock painting, cover the work’s reverse—in the same color and pattern that appear on the back of Untitled (c. 1950–53)—suggesting Pollock gave Krasner his spare canvas from the barn for her to work with. A ghostly rectilinear form without paint behind Equilibrium indicates that the canvas used for Untitled once laid on top of it, likely while still in the barn and before Krasner used the material for her own works. On its face, opposing directions of paint drips suggest Krasner rotated Equilibrium while working, as is the case with loosely-brushed paintings of side-by-side rectangles in saturated palettes of orange, purple, and green (c. 1950–53). Drips of paint around these painting’s edges indicate that Krasner worked on these paintings flat on a surface, consistent with the technique she used to create the “Little Images.”

Krasner would not exhibit these paintings of squares in her lifetime, but they signal a Matissean exploration of color and form that would be fully realized in Blue and Black (1951–53), shown in Krasner’s first major New York museum solo show at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1973 and reproduced on the accompanying exhibition poster. Using a single hue to create a sense of volume and build energetic surface tension, Krasner depicts duplicate filigree motifs within vertical bands of blue and black paint in this work. Krasner’s encounters with Matisse’s paintings at the Museum of Modern Art began decades earlier, most significantly during his 1931 retrospective. As with Blue and Black, Krasner’s paintings of squares recall a key formal contradiction in Matisse’s The Red Studio (1911), where the foreshortened floor line falls flat against the wall, rendered in the same luxurious red color that pulls the background to the fore. Krasner likely saw this painting installed on the museum’s ground floor upon its acquisition in 1949. Regarded as the most important work by Matisse to enter the museum’s collection at the time, the painting also featured alongside his recent cut-outs in a major retrospective that opened in November 1951, just ten days after the close of Krasner’s show at Betty Parsons.[8] Frustrated by the lackluster reception to her show, Matisse’s vibrant, scissor-cut works would impart a lasting impression on Krasner who, soon enough, would take scissors to her own work.

“Numbers are neutral. They make people look at a picture for what it is—pure painting.” –Lee Krasner

Krasner’s exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery opened on October 15 and ran through November 3 of 1951. Parsons also showed a suite of collages by the American artist Anne Ryan during the same three-week stretch, and so the show is sometimes described as a two-person exhibition. But the gallery ran separate advertisements for Krasner and Ryan, indicating the singularity of each presentation. A price list from Krasner’s exhibition, dated October 1951, indicates Krasner assigned numbers in lieu of conventional titles to her works.[9] Her decision to do so recalls a similar strategy used by Pollock, whose career had already taken off. Around the time he began employing his signature drip technique in the late 1940s, Pollock ceased assigning titles to his work in favor of numbers. Krasner’s comments on Pollock’s works are telling about her own reluctance to assign conventional titles. Sometime in the summer of 1950, the writer Berton Roueché visited Springs to interview Pollock on the occasion of his inclusion in the 25th Venice Biennale. Roueché also spoke with Krasner during the visit, even pulling her praise of the “unframed space” in Pollock’s paintings for his article’s title. On Pollock’s paintings, Krasner told Roueché, “Numbers are neutral. They make people look at a picture for what it is—pure painting.”[10] In fact, Krasner was asked to complete a questionnaire related to Number 3, its creation, and its subsequent history upon its acquisition by MoMA. But on the questionnaire, dated January 28, 1970, Krasner declined to offer the museum any description or anecdote related to the work—she replied simply “No” to six of the museum’s questions about her artistic process, exceptional circumstances or incidents related to its history, and its title.[11] Despite that she began reusing and discarding related canvases as early as 1953, her disinclination to discuss any external associations related to the work suggests that, almost two decades later, she had not budged on her position that a painting should speak for itself.

At the close of Krasner’s show, not a single painting had sold. As author Mary Gabriel has observed, uncertainty defined Krasner’s only exhibition with Betty Parsons. Even Krasner’s age was a cause for question: Krasner turned forty-three during the course of the show, but the biographical details printed to accompany the paintings suggested she was born three years later than in reality. [12] As a crowd began to form at the opening reception, Pollock could be heard clarifying for a guest, “This is Lee’s show” before disappearing to the street—a remarkably calm reaction from Pollock who, according to Gabriel, would typically subject Krasner to drunken resentment when he felt threatened by her accomplishments.[13] “It was worse than I feared…I felt badly for Lee,” Parsons once recounted.[14] Pollock’s fifth solo exhibition with Parsons opened shortly after Krasner’s closed. Dissatisfied with his sales at the gallery, it would be Pollock’s last with Parsons before Krasner arranged for his joining the powerhouse Sidney Janis Gallery in 1952. When Pollock left, Parsons asked Krasner to leave her gallery as well, telling Krasner that her fate had less to do with the quality of her work than with the pain of Pollock’s departure from the gallery roster. For Krasner, the verdict proved devastating: “It took me almost a year to recover from that shock before I could work again…I was kicked out of the gallery because I was Mrs. Jackson Pollock.”[15]

The mixed, but generally positive critical reception to Krasner’s show was littered with sardonic compliments and diminutive, gendered adjectives. Several reviewers noted the likeness of Krasner’s compositions to those of Piet Mondrian, the Dutch abstractionist widely known for his use of primary colors on white grounds divided by vertical and horizontal black lines. “Roughly, here is the Mondrian formula worked out with feminine acuteness and a searching for formal and chromatic harmonies rather than a delivery of water-tight solutions.…No. 2, whose majestic and thoughtful construction is carried right through to the four sides of the canvas, can be appreciated even by those blissfully ignorant of the ‘right’ attitude,” wrote Stuart Preston for The New York Times. Dore Ashton for The Art Digest detailed how Krasner’s forms occasionally “give way to right-angle tensions related to Mondrian in structure, if more sensuous in color.” According to another reviewer, identified as Emily Genauer for New York Herald Tribune by Krasner’s biographer Gail Levin, Krasner painted “in mural-like grandeur the most restrained and pacific of designs, largely confined to geometric spaces and gentle colors.…Several of her designs suggest a purification of Mondrian, whose rigid formalism has been purged of all harshness…What touches the observer most are painted surfaces which are beautifully smoothed into quietly innocuous patterns of arresting, sweetly cultivated tonal composition.”[16] The message was clear: the reviewers belittled Krasner’s work, deeming it less serious than that of her male counterparts, especially when compared to the critical praise and international fame Pollock had begun to receive.

If Krasner cringed when reading of her “love for delicate, closely related color tonalities,” as Ashton put it, the reviews may also have reminded her of her earlier friendship with Mondrian, which proved formative in her development as an artist. Krasner had been exposed to Mondrian’s work over a decade before the Parsons show. He would not arrive in New York until 1940, but he had already found an audience among American abstract artists through the 1930s, publishing an important essay in English translation in 1937 and finding his way into collections like A. E. Gallatin’s Museum of Living Art, a key venue for the display of European avant-garde art. There, Krasner likely saw works including Mondrian’s Composition with Blue and Yellow (1932) while enrolled in art classes with the German émigré painter Hans Hofmann in the late 1930s. Hofmann’s lectures on Mondrian were especially influential to Krasner, who absorbed Hofmann’s “push and pull” technique of using color to create pictorial space on a two-dimensional surface in these years. But she would soon grow irritated with Hofmann’s insistence on modeling space from life, favoring Mondrian’s approach to creating pictures that did not pretend to represent scenes from nature; around 1940, her early Cubist-inspired paintings employing boldly-outlined shapes in primary colors would transform into works clearly indebted to Mondrian. On her time at Hofmann’s school, Krasner even recounted her divergence from Hofmann’s methods when she stated to art historian Barbara Novak in 1979, “I might do a vertical or horizontal measurement of space…so it looked like a Mondrian,” recalling the language she used to describe Number 2 to Seckler in 1967.[17]

Krasner would eventually meet Mondrian in 1941 after joining the American Abstract Artists, a group of avant-garde artists providing exhibition opportunities to abstractionists who at the time lacked critical and institutional support. Several of Krasner’s friends and acquaintances, such as Giorgio Cavallon, later Krasner’s neighbor in Springs, founded the group in 1936. They largely aligned themselves with Mondrian’s theoretical position—that abstract compositions offered closer views of reality than illusionistic depictions of the visible world—and they quickly invited the Dutch artist to join the group upon his arrival in New York.[18] Their commitment to non-objectivity contrasted the social realist style preferred by many artists affiliated with the Works Progress Administration. Krasner had earlier worked on the mural division of the WPA, but eventually grew tired of its didacticism.[19] In April 1940, she picketed MoMA with the American Abstract Artists for neglecting to show abstract art in the 1939 exhibition Art of Our Time; two months later, she exhibited in the group’s fourth annual exhibition for the first time. At a party to welcome Mondrian and the French artist Fernand Léger to the group in February 1941, Krasner and Mondrian discovered their shared love of jazz, and they soon made a date to dance together at Barney Josephson’s progressive Café Society. As she once recalled of his dancing, “It seems to me his movement was all vertical, up and down…maybe I had been too affected by his painting before I met him.”[20]

According to art historian Anne Wagner, Krasner’s compositions share the dynamism of another American who shared the challenges of being both a woman and an artist at midcentury: Irene Rice Pereira. Pereira was one of three women in MoMA’s exhibition Fourteen Americans in 1946; she was also one of seven women, along with Anne Ryan, included in the survey exhibition Abstract Painting and Sculpture in America, staged at the museum from January to March 1951.[21] Pereira’s Composition in White (1942), which Wagner points out was included in both of these exhibitions, generates a similar optical pulse made of horizontal and vertical lines as found in Krasner’s works such as Number 2. Krasner would have been familiar with Pereira by at least April 1940, when her name appears on the Ad Reinhardt-designed leaflet distributed at the MoMA protest.[22] She also exhibited alongside both Pereira and Mondrian in February 1941, in the American Abstract Artists’ fifth annual exhibition.[23] Krasner once recounted viewing the exhibition with Mondrian, stating he had very few comments on most of the paintings in the show. But as they approached Krasner’s painting, he told her: “You have a very strong inner rhythm. Never lose it.”[24]

Krasner prepared for her Betty Parsons show in Springs, a small hamlet in East Hampton, New York. Krasner and Pollock had purchased a house there shortly after their marriage in 1945, with a loan from Peggy Guggenheim, the stalwart collector and dealer who gave Pollock his first solo exhibition in 1943. Within a year, Pollock moved the barn to the north side of the property and began his studio renovations while Krasner set up in the bedroom. The two artists kept their spaces separate, and one only entered the other’s upon invitation.[25] Krasner experienced her first major break in that room with the emergence of her “Little Images,” best known for their relatively small size, thick paint layers, and reluctance to regard one area of the composition as more important than any other. In positing the “Little Images” as a major contribution to the history of Abstract Expressionism, feminist art historian Cindy Nemser divided the series into three occasionally overlapping categories: the earliest works were heavily stroked, jewel-like abstractions, while later works were hieroglyphic in character or adopted a weblike, skein format.[26] In a 1973 interview with Nemser, Krasner recounted the emergence of this series after a long period of creative block. Working with the canvas on the floor or a table, Krasner created these works by applying paint directly from the tube or with a palette knife. Sometimes she worked into the surfaces with a stiff brush, and other times covered the canvas with paint thinned with turpentine in a can. She preferred the sensuousness of oil paint to fast-drying acrylic (whose opaque density she described as “dead as a doornail”), lending to a distinct sensibility to the works.[27]

The “Little Images” would take a decidedly geometric turn around 1948, after Krasner created two landmark mosaic tables in late 1947 and 1948. That winter was bitterly cold, best remembered for a historic blizzard that dumped record levels of snowfall on the northeastern United States.[28] Krasner and Pollock could not afford to heat the upstairs bedroom due to financial strain, leaving Krasner without her painting studio, so she began working downstairs to stay warm. Adopting two old iron rims of wagon wheels found in the barn for the tables’ frames, Krasner improvised their designs with broken glass, seashells, pebbles, and other material. As Gail Levin has observed, Krasner had previously attended lectures on mosaics at the National Academy of Design in New York, where she had briefly studied in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and she had helped prepare the design for a colleague’s mosaic while on the WPA in the 1930s.[29] The mosaic tables mark a significant milestone in Krasner’s career. Not only do their assembled surfaces prefigure Krasner’s penchant for collage which will define a major breakthrough in the mid 1950s—not to mention a major mosaic mural commission at the Uris Brothers Building in New York completed in 1959—but they also earned Krasner her first critical praise without reservation, according to Levin. Upon exhibiting the first of the two tables in a group exhibition at Bertha Schaefer Gallery in 1948, the New York Herald Tribune praised Krasner’s table as “magnificent” and illustrated the work, which Levin identifies as probably the first reproduction of Krasner’s work to ever be published; The New York Times offered similar acclaim.

Following the positive reception of the tables, many “Little Images” began to adopt the grid-like structure that Number 2 seems to disassemble and refashion at a monumental scale. Perhaps the act of physically arranging the isolated tesserae of the tables’ surfaces renewed Krasner’s interest in geometric relationships. Krasner reused the round, wooden base for the tables as a support for a “Little Image” painting, the only tondo she would ever create, underscoring the direct connection between Krasner’s tables and this series of paintings. She sometimes restricted her palette to black and white and other times illustrated her works with vibrant colors, creating patterns of squares reminiscent of Mondrian’s rhythmic Broadway Boogie Woogie. In some, the grids organize dense arrangements of symbols that Krasner described as “hieroglyphs.”[30] These elements include triangles, circles, zigzags, and swirling lines reminiscent of the spiral foram shells Krasner collected in Springs. Krasner’s calligraphic markings resemble their own writing system, inviting one to read the marks in sequential order. Writing of an untitled 1949 example at MoMA, the influential arts journalist Grace Glueck even observed that the “Little Images” appear to anticipate Jasper Johns’ well-known gridded sequences of numbers and letters.[31] Mary Gabriel notes that Krasner had earlier studied Persian, Arabic, and Celtic calligraphy at The Morgan Library & Museum in New York, and this interest would later resurface in major paintings like Kufic (1965), shown with Blue and Black at the Whitney in 1973. [32]

In fact, curator Marcia Tucker once pointed out to Krasner that she painted from right to left, consistent with how one would write in Hebrew. Born in Brooklyn, New York, to an Orthodox Jewish family speaking a mixture of Russian, Yiddish, and English in the household, Krasner studied the Hebrew alphabet as a child, though she could never fluently read or write the language.[33] In these paintings, there is no one way to enter a sequence—whether left-to-right or top-to-bottom, the works remain open-ended, as if suspended in a story with no beginning, middle, or end. The geometric character of these works is undeniable, but when Nemser suggested the “Little Images” integrate the geometric and the organic, Krasner replied, “I merge what I call the organic with what I call the abstract, which is what you are calling the geometric.”[34] Her remark suggests the format of the grid enabled Krasner to, from her point of view, expand her budding abstract vocabulary.

Krasner was increasingly proud of her visual language, hanging her “Little Images” for guests to see in her home in Springs. The critic Clement Greenberg, whose opinion Krasner respected, exclaimed when he saw an early example, “That’s hot. It’s cooking.”[35] Krasner was surely pleased by this remark. Greenberg had solidified his reputation as a leading critic through the 1940s, and his writing proved foundational in establishing Pollock’s reputation. In fact, it was his words about Pollock that Life magazine would adapt into their memorable headline—“Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?”—in 1949. As Krasner would later recall to curator Barbara Rose, “I didn’t hide my paintings in a closet; they hung on the wall next to my husband’s.”[36]

By the summer of 1950, in what Rose has deemed Krasner’s “year of decision,” Krasner realized a break in her paintings.[37] She began automatic drawing experiments with paint in a semi-figurative style. Indicative of a newfound sense of confidence, she began insisting her guests in Springs see her studio in the upstairs bedroom, when previously they would only venture into Pollock’s in the barn. Her confidence could only have been bolstered in July 1950, when one of her paintings won second prize, ahead of Pollock’s third prize, in the group exhibition Ten East Hampton Abstractionists at Guild Hall Museum.[38] At the opening reception of this exhibition, Krasner and Pollock met the German photographer Hans Namuth who, at Krasner’s encouragement, would soon photograph Pollock at work in his studio. But Namuth would also take his camera into Krasner’s studio that summer. The freely improvised paintings that Namuth saw, which were still in progress, only survive in his photographs. They appear to be paintings of bold, linear white forms on dark grounds, recalling the palette of “Little Images” like White Squares (c. 1948). As Rose has argued, these “Personage” paintings, Krasner’s first automatic works to allude to the figure, demonstrate a knowledge of the lanky figures of Joan Miró’s “Peintures Sauvages,” which Krasner would have seen at Miró’s retrospective at MoMA in late 1941.

Krasner destroyed many of the paintings she made in this period, but Gothic Frieze (1950) and Promenade (c. 1950) are among the closest extant examples of this style. With its organic forms recalling those found in Pollock’s Mural, commissioned by Peggy Guggenheim in 1943, Promenade affirms Krasner’s interest in verticals endured through her automatic experiments. In Gothic Frieze, Krasner’s bold linework gives way to sharp black and white lines and applications of red, green, and yellow paint that open into a network of triangles, circles and semicircles. The rough texture of this work’s Masonite support peers through the paint layers, which Rose would further credit to Miró’s paintings.[39] Not only do Krasner’s linear forms and somber palette look forward to her explosive “Umber” series of monumental paintings made in the wake of Pollock’s sudden death in 1956, especially Gothic Landscape (1961), but her work also recalls a painting of Pollock’s, Gothic (1944, MoMA), which remained in the couple’s possession and which Pollock had exhibited as recently as 1948.[40] But Krasner’s shapes are far more pointed and interconnected than Pollock’s, creating an intricate geometric pattern. Aside from its similarity to Pollock’s, Krasner’s title further invokes both a prominent architectural style in early modern Europe as well as an ornamental element found in ancient Greek and Roman architecture.

Krasner’s early career as a mural painter would certainly have fostered her thinking about painting’s relationship to architecture, a discipline that uses geometry to study space and draft plans. She would have revisited this focus in late 1949, when the architect Peter Blake’s designs for an unrealized “ideal museum” to house Pollock’s paintings were exhibited in Pollock’s third exhibition at Betty Parsons. In fact, when Berton Roueché borrowed Krasner’s term “unframed space” for the title of his interview in the summer of 1950, Krasner herself seems to have taken these words from the title of architecture curator Arthur Drexler’s article on Blake’s designs in the January 1950 issue of Interiors magazine.[41] In the summer of 1950, around the time Namuth photographed the “Personage” paintings in progress in Krasner’s studio, the Swiss-French modernist architect Le Corbusier visited Springs to realize a mural in the home of the Italian sculptor Costantino Nivola, Krasner and Pollock’s neighbor. Though he was generally wary of the Abstract Expressionists, Le Corbusier visited Krasner and Pollock’s home with Nivola and was pleased to find a copy of his book in the couple’s library. Given the time of his visit, he must have seen either Krasner’s “Little Images” hanging on the walls if not the experimental “Personages” in her studio when he stated, however condescendingly: “This man [Pollock] is like a hunter who shoots without aiming. But his wife, she has talent—women always have too much talent.”[42]

When she and Pollock returned to New York City in early 1951, Krasner briefly shared Helen Frankenthaler’s 21st Street studio, where she would further develop the experiments she began the previous summer. By now, Krasner held a reputation as a “good critic,” in Frankenthaler’s words.[43] She was likely conscious of the impression she would make on Frankenthaler, who was twenty years Krasner’s junior, and the works executed in these months demonstrate an impressive boldness and confidence that endured through the spring of 1951. It was in this context that Pollock persuaded Betty Parsons, with whom he began exhibiting when Peggy Guggenheim closed her gallery and moved to Italy in 1947, to visit Springs and view Krasner’s works. Krasner was thrilled by Pollock’s promotion of her work to Parsons, which seemed to confirm that her new direction was proving successful. Based on the strength of the new paintings, Parsons added Krasner to her exhibition schedule after the studio visit, and Krasner quickly began to prepare for the occasion. In a rare moment of praise, Pollock described Krasner’s productivity in Springs in a letter to friends and neighbors Alfonso Ossorio and Ted Dragon: “Lee is doing some of her best painting—it has a freshness and bigness that she didn’t get before—I think she will have a handsome show.”[44] But when Parsons visited Springs, she saw works like Gothic Frieze and Promenade, realized in this new experimental style—not the rectangles and vertical shapes, more restrained by comparison, of Number 2 or Number 3 that Krasner delivered in the fall.

Something happened between the spring and fall of 1951 that caused this dramatic shift in style. Perhaps it was the pressure Krasner felt to establish her own career in the shadow of her husband’s. Pollock’s profile in the August 1949 issue of Life magazine had catapulted him to national fame, reaching an international audience with a 1950 solo exhibition at Museo Correr in Venice to coincide with his participation in the Biennale. When Krasner answered Barnett Newman’s phone call in May 1950, it was Pollock that Newman asked to speak to, inviting him—and not Krasner—to sign an open letter protesting the director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s public contempt for modern painting, resulting in an iconic photograph of a group of vanguard artists dubbed “The Irascibles” in Life the following January.[45] Although Krasner was fully in support of Pollock’s career and worked tirelessly to advance it, she must have felt frustrated about her own artistic identity, especially as a distinctive character among the New York avant-garde emerged with the historic Ninth Street Show, in which Krasner participated in the spring of 1951.

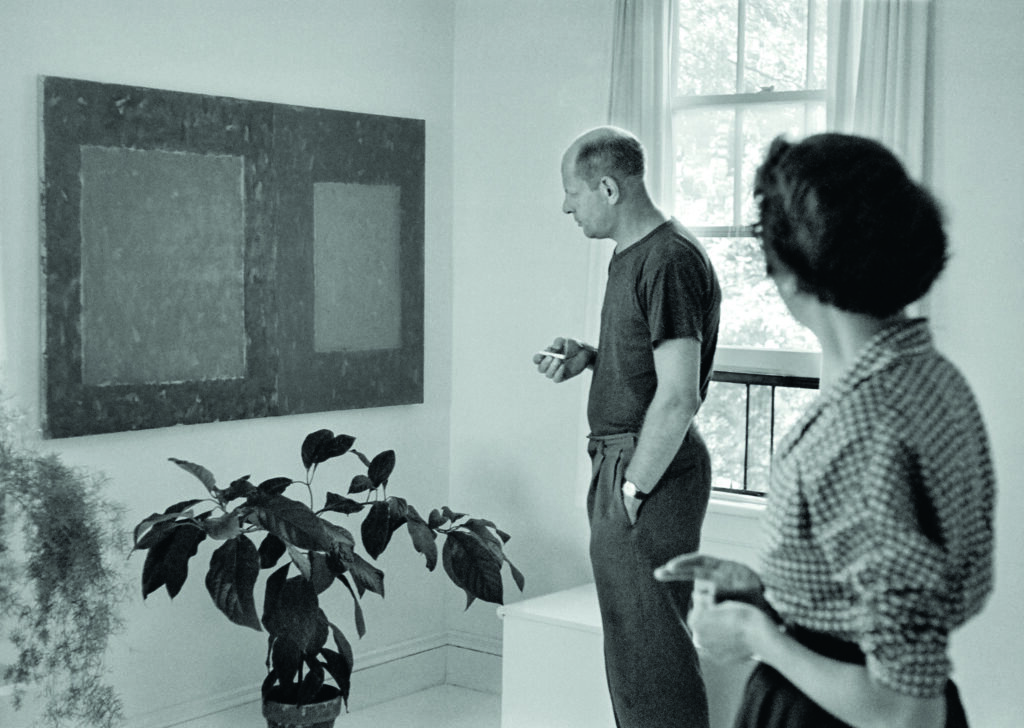

Many of Krasner’s friends admired her new, freer style, but Krasner’s ultimate benchmark of success remained the approval of the critics. When Greenberg visited her studio and saw similar works, he delivered an unexpected reaction: while supposedly looking at Krasner’s paintings, he studied the paint on the bedroom wall and remarked, “Gee, that’s fascinating.”[46] Though Krasner remained hopeful for an exhibition review, Greenberg did not write about the show, surely to the artist’s disappointment and likely making the other reviewers’ gentle derision all the more irritating. Although Krasner’s confidence was shot and she apparently stopped painting for nearly a year after the exhibition, she seems to have bounced back by August 1953, when Life magazine sent photographer Tony Vaccaro to Krasner and Pollock’s home. A selection of photographs from the visit, which Life ultimately did not publish, show Krasner posing in front of an untitled painting hanging in their home. Looking fiercely at the camera, Krasner exudes a sense of pride about the work. Another view shows Krasner and Pollock looking intently at the painting in a rare photograph that documents Pollock critiquing one of Krasner’s works instead of vice versa. After a long period of creative distress after leaving Betty Parsons Gallery, Krasner had finally regained self-assurance as an artist.

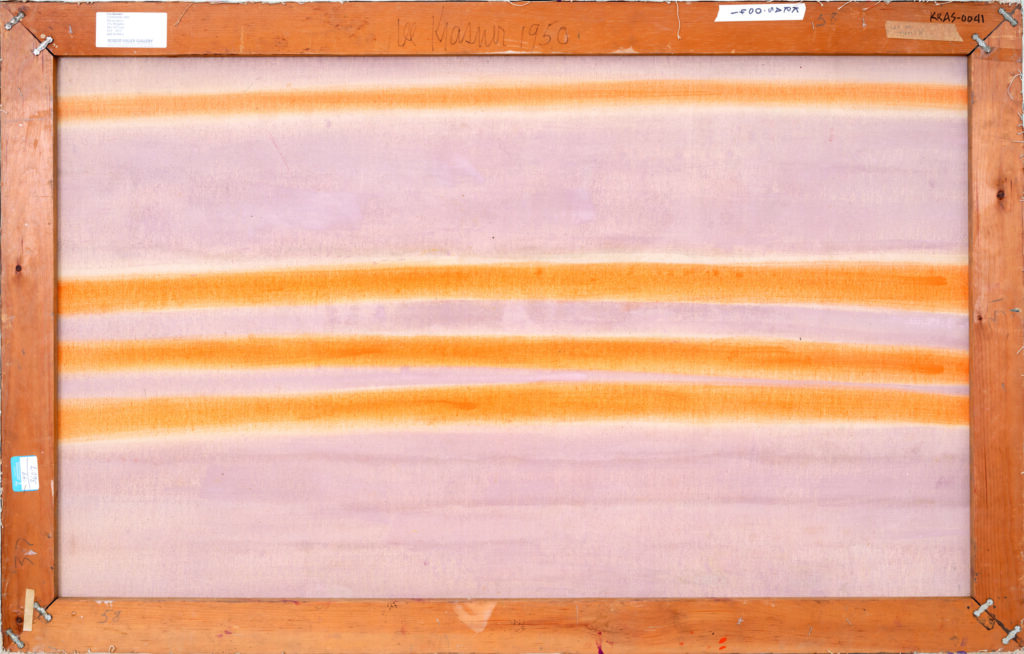

Vaccaro’s photographs confirm that Krasner completed Untitled sometime before August 1953. Krasner’s inscription on the back of the painting dates it to 1950, the same year she began her automatic painting experiments, but close observation of the work offers a more puzzling picture. Krasner realized this work and its sister paintings of side-by-side squares on reused canvases, and the original paint layers remain semi-visible from the reverse. The underlying compositions appear remarkably consistent with the works Krasner exhibited at Betty Parsons, which she began sometime after Parsons’ visit to her studio in the spring of 1951. Take Untitled, also inscribed “1950,” in which bright orange and light purple bands of paint appear underneath the present picture of deep purple squares. The purple bands are even reminiscent of the “mauves” that Dore Ashton mentioned in her exhibition review for The Art Digest.[47] It remains plausible that Krasner first worked on this canvas ahead of her exhibition at Parsons’ gallery and subsequently painted over it with the present picture before August 1953. The exhibition price list suggests the fourteen canvases were priced in three tiers, presumably based on the size of the works: Number 2 was by far the largest; eight paintings were priced at a second tier; and five paintings were priced at a third tier, creating the possibility that they were the size of Untitled.

Krasner even applied a layer of gesso over the original paint film before painting Untitled. This technical observation both affirms that Krasner realized Untitled as a new painting, instead of reworking an old one, and it also suggests that the underlying work was probably dry at that time. Given the length of time that oil paint takes to dry, Krasner could have realized Untitled long after the close of her Betty Parsons show, when she returned to painting “almost a year” after Parsons asked her to leave the gallery in 1952.[48] Perhaps, then, Krasner signed and dated Untitled at a later time, ultimately inscribing an earlier date as is apparently the case with a related gouache on paper.[49] In this case, the painting confirms that when Krasner finally returned to painting after the Betty Parsons show, she did not immediately give up on geometric abstraction. She retained the imagery and iconography that she long associated with abstraction, and her interest in geometric shapes, especially vertical stripes, would routinely resurface throughout her career. In fact, soon after MoMA’s acquisition of Number 3 in 1969, Krasner would find new interest in fusing hard-edge geometry with imagery based on nature, as seen in a vertical band at the center of Rising Green (1972).

By the time Krasner posed with her painting for Tony Vaccaro, she finally had her own outdoor studio next to the barn, in a former smokehouse on a newly acquired acre of land adjoining her property in Springs.[50] Eager to embark on a new direction after a long period of self-doubt, Krasner began a series of black and white drawings which she pinned along her studio walls, from floor to ceiling. She recalled entering the studio one day and, dissatisfied with what she saw, tearing the drawings into pieces. She would not return to the studio for weeks, but when she finally did, she found herself intrigued by the strewn pieces of paper on the floor. “I began picking up torn pieces of my own drawings and re-gluing them. Then I started cutting up some of my own oil paintings. I got something going there and I started pulling out a lot of raw canvas and slashing it as well. That’s how I started my collaging and the tail end of it was the collaging of the paintings in the Betty Parsons show.”[51] The experiments would result in a significant body of work that Krasner would present to critical acclaim in 1955, four years after the Betty Parsons show. Greenberg would later describe the works as “a major addition to the American art scene,” establishing Krasner’s standing among her Abstract Expressionist peers.[52] Soon enough, Krasner took an entirely new approach to her paintings. With her first collage paintings in 1953, Krasner would break again.

A pioneer among the first generation of Abstract Expressionism, Lee Krasner (1908–1984) developed novel approaches to painting and collage for over half a century, demonstrating an endless drive for experimentation and reinvention. Widely recognized as a central protagonist among a cohort of artists that define postwar American painting, Krasner was subject to a critically-acclaimed major touring European institutional retrospective organized by the Barbican Art Gallery in 2019–21, followed by a solo exhibition at the Carolyn Campagna Kleefeld Contemporary Art Museum in 2023. She was subject to two touring US institutional retrospectives in 1984–85 and 1999–2001. Her work is held in premier institutions worldwide, including the Museum of Modern Art, New York; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, among many others.

Jason Drill is an art researcher and writer based in New York. He is Head of Research at Kasmin. His writing has appeared in the Brooklyn Rail.

Lee Krasner: The Edge of Color

2024

Softcover

ISBN: 978-1-947232-02-0

Dimensions: 9.5 x 11.125 inches

Pages: 88

Kasmin Books is pleased to present a fully-illustrated catalogue to accompany the major exhibition Lee Krasner: The Edge of Color, Geometric Abstractions 1948–53, Replete with 18 color plates, related archival material, and newly-commissioned texts by Adam D. Weinberg, Director Emeritus of the Whitney Museum of American Art, and Jason Drill, Head of Research at Kasmin, the catalogue foregrounds a rarely-examined chapter of Krasner’s five-decade career, now available for order.

Notes

[1] Ellen G. Landau, manuscript notes from an interview with Lee Krasner, October 30, 1979. LKCR 252, Box 7, Lee Krasner Catalogue Raisonné Archive, 1929–1983, Pollock-Krasner Study Center, Southampton, NY, Collection: 1996.02.

[2] Krasner, to Seckler, December 14, 1967.

[3] Landau, manuscript notes, October 30, 1979.

[4] Krasner, to Seckler, November 2, 1964.

[5] Ellen G. Landau, “Lee Krasner’s Early Career, Part Two: The 1940s,” Arts Magazine 56 (November 1981), p. 89n54.

[6] Krasner, interview with Phyllis Braff, “From the Studio,” The East Hampton Star (August 21, 1980), p. II-8.

[7] Krasner, to Seckler, December 14, 1967.

[8] “EXHIBIT OF TWO MAJOR ACQUISITIONS,” April 5, 1949. MoMA Press Release Archives, The Museum of Modern Art, New York. MoMA’s acquisition of Matisse’s The Red Studio was covered in The New York Times on Wednesday, April 6, 1949, p. 35. Krasner probably first saw Matisse’s cut-outs when they were exhibited at Pierre Matisse Gallery in 1949; see Eleanor Nairne, “To Breathe and Be Alive,” in Eleanor Nairne, ed., Lee Krasner: Living Colour, exh. cat. (London: Thames & Hudson in association with Barbican Art Gallery, 2019), pp. 16, 223n36.

[9] Betty Parsons Gallery records and personal papers, 1916–1991, bulk 1946–1983, Box 9, Folder 13: Krasner, Lee, 1949–1983 (frame 3). Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[10] Krasner, quoted in Berton Roueché, “The Talk of the Town: Unframed Space,” The New Yorker (August 5, 1950), p. 16.

[11] Artist’s Questionnaire, January 28, 1970. Museum Collection Files, Lee Krasner, Number 3 (Untitled) (1951). Department of Painting and Sculpture, The Museum of Modern Art, New York.

[12] Mary Gabriel, Ninth Street Women: Lee Krasner, Elaine de Kooning, Grace Hartigan, Joan Mitchell, and Helen Frankenthaler: Five Painters and the Movement That Changed Modern Art (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2018), p. 417; see a biographical record issued by Betty Parsons Gallery at the time of Krasner’s show, which lists her birth year as 1911. In fact, Krasner was born three years earlier, in 1908. Betty Parsons Papers, Box 9, Folder 13 (frame 7).

[13] Jackson Pollock, quoted in Gabriel, Ninth Street Women, p. 417.

[14] Betty Parsons, in Jeffrey Potter, To A Violent Grave: An Oral Biography of Jackson Pollock (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1985), p. 146.

[15] Krasner, in Cindy Nemser, Art Talk: Conversations with 12 Women Artists (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1975), p. 94. An abridged version of this interview was published in Arts Magazine in April 1973.

[16] Stuart Preston, “Among One-Man Shows,” The New York Times (October 21, 1951), p. 8; Dore Ashton, “Lee Krasner,” The Art Digest (November 1, 1951), pp. 59, 61; [E.G.], “Abstract and Real,” unidentified newspaper clipping, circa October 1951, Betty Parsons Papers, Box 9, Folder 13 (frame 12); see Robert Goodnough, “Lee Krasner,” Art News (November 1951), p. 53.

[17] Krasner, to Barbara Novak for WGBH New Television Workshop, Boston, October 1979. Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner papers, circa 1914–1984, bulk 1942–1984, Box 10, Folder 5: Barbara Novak Interview, 1979 (frame 20). Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Quoted in Gail Levin, Lee Krasner: A Biography (New York: William Morrow, 2011), p. 127.

[18] Barbara Rose, “Mondrian in New York,” Artforum 10, no. 4 (December 1971), p. 55.

[19] Krasner was one of many leftist artists and writers who grew disillusioned with social realism after the Moscow Trials (1936–38) and the German-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact (1939) on the cusp of World War II. See Gail Levin, “Reflections: My First Interview with Lee Krasner” (Marlborough Gallery, New York, February 6, 1971), reprinted in Nairne, Living Colour, p. 173; see Gabriel, Ninth Street Women, p. 34.

[20] Krasner, interview with Barbara Novak, videotape courtesy of the Pollock-Krasner House and Study Center, East Hampton, NY. Quoted in Gabriel, Ninth Street Women, p. 82.

[21] Anne M. Wagner, “Krasner’s Fictions,” in Three Artists (Three Women): Modernism and the Art of Hesse, Krasner, and O’Keeffe (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), p. 167; see Levin, Biography, pp. 274–275.

[22] Krasner later told artist Doloris Holmes that she was aware of Pereira’s work by at least the late 1930s; see Oral history interview with Lee Krasner, 1972. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution; see Levin, Biography, p. 392.

[23] Edward Alden Jewell, “Abstract Artists Put On Exhibition,” The New York Times (February 11, 1941), sec. L, p. 28. Among the other exhibitors were Bauhaus artists Josef Albers and László Moholy-Nagy.

[24] Lee Krasner Papers, Box 9, Folder 47: Barbara Rose Interview, 1972 (frame 4).

[25] Krasner, to Barbara Rose, “American Great: Lee Krasner,” Vogue (June 1972), p. 154.

[26] Cindy Nemser, “Lee Krasner’s Paintings, 1946–49,” Artforum 12, no. 4 (December 1973), pp. 61–65.

[27] Krasner, in Nemser, Art Talk, p. 89.

[28] The blizzard was covered in The New York Times on Sunday, December 28, 1947 and documented in photographs in the January 5, 1948 issue of Life magazine.

[29] Levin, Biography, p. 250.

[30] B. H. Friedman, “Introduction,” in Lee Krasner: Paintings, Drawings, and Collages, exh. cat. (London: Whitechapel Gallery, 1965), p. 10.

[31] Grace Glueck, “Art: Lee Krasner Finds Her Place in Retrospective at Modern,” The New York Times (December 21, 1981), sec. C, p. 31.

[32] Gabriel, Ninth Street Women, p. 178.

[33] Levin, Biography, p. 245.

[34] Krasner, in Nemser, Art Talk, p. 90.

[35] Nemser, Art Talk, p. 91.

[36] Krasner, to Rose, Vogue, p. 154.

[37] Barbara Rose, Lee Krasner: A Retrospective, exh. cat. (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1983), p. 65.

[38] Steven Naifeh and Gregory White Smith, Jackson Pollock: An American Saga (New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc., 1989), p. 641.

[39] Rose, Retrospective, p. 66. Krasner would elsewhere cite Miró’s “painterliness” as a major influence on both Pollock’s and her work, indicating her close examination of the surfaces of Miró’s paintings. See Krasner’s comments to Levin, in Nairne, Living Colour, p. 178. Emphasis in original.

[40] Francis Valentine O’Connor and Eugene Victor Thaw, Jackson Pollock: A Catalogue Raisonné of Paintings, Drawings, and Other Works, Vol. 1: Paintings, 1930–1947 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1978), p. 98.

[41] Drexler would later become curator and director of the Department of Architecture and Design at the Museum of Modern Art.

[42] Le Corbusier, as recounted by Costantino Nivola, in Potter, Violent Grave, p. 200; see Jessica Freeman-Attwood’s chronology in Nairne, Living Colour, p. 205; see Levin, Biography, p. 265.

[43] Helen Frankenthaler writes about Krasner and the shared studio to Sonya Gutman (Rudikoff) in two letters, dated January 17, 1951 and January 30, 1951. Sonya Rudikoff Papers, 1935–2000 (C1493), Series 1: Helen Frankenthaler Correspondence, 1949–2005, Box 1, Folder 3, Manuscripts Division, Department of Special Collections, Princeton University Library. Quoted in Gabriel, Ninth Street Women, p. 406.

[44] Pollock, letter to Alfonso Ossorio and Ted Dragon, June 7, 1951, printed in O’Connor and Thaw, Jackson Pollock Catalogue Raisonné, Vol. 4: Other Works, 1930–1956, p. 261; see Gabriel, Ninth Street Women, p. 409; see Levin, Biography, p. 273.

[45] Krasner, to Holmes, 1972; see Levin, Biography, pp. 262–263.

[46] Clement Greenberg, as recounted by Alfonso Ossorio, in Potter, Violent Grave, p. 139.

[47] “Canvases in this show are not titled, but 7, 11, and 3—with their leaning lines, their subtle deviations from rigid verticality and muted greys, yellows, and mauves—create a harmony unusual for this genre of painting.” Ashton, Art Digest, p. 61.

[48] Krasner, in Nemser, Art Talk, p. 94. Given that Parsons convinced Pollock to stay with her gallery until the spring of 1952, and presumably asked Krasner to leave thereafter, Krasner could have returned to painting as early as the spring of 1953. This observation supports Jeffrey Grove’s commentary in his chronology published in Ellen G. Landau, Lee Krasner: A Catalogue Raisonné (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1995), p. 311.

[49] The gouache on paper is inscribed “48” in pencil, but it was probably realized later than 1948, closer to the time of these oil paintings of squares and rectangles. See Ellen G. Landau’s remarks on CR 238 in Landau, Lee Krasner Catalogue Raisonné, p. 116.

[50] Levin, Biography, p. 290.

[51] Krasner, to Nemser, Art Talk, pp. 93–94.

[52] Friedman, Krasner, p. 4.

Artworks © 2024 Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.