“In the 1940s, an avant-garde scene emerged alongside the city’s commercial film industry.”

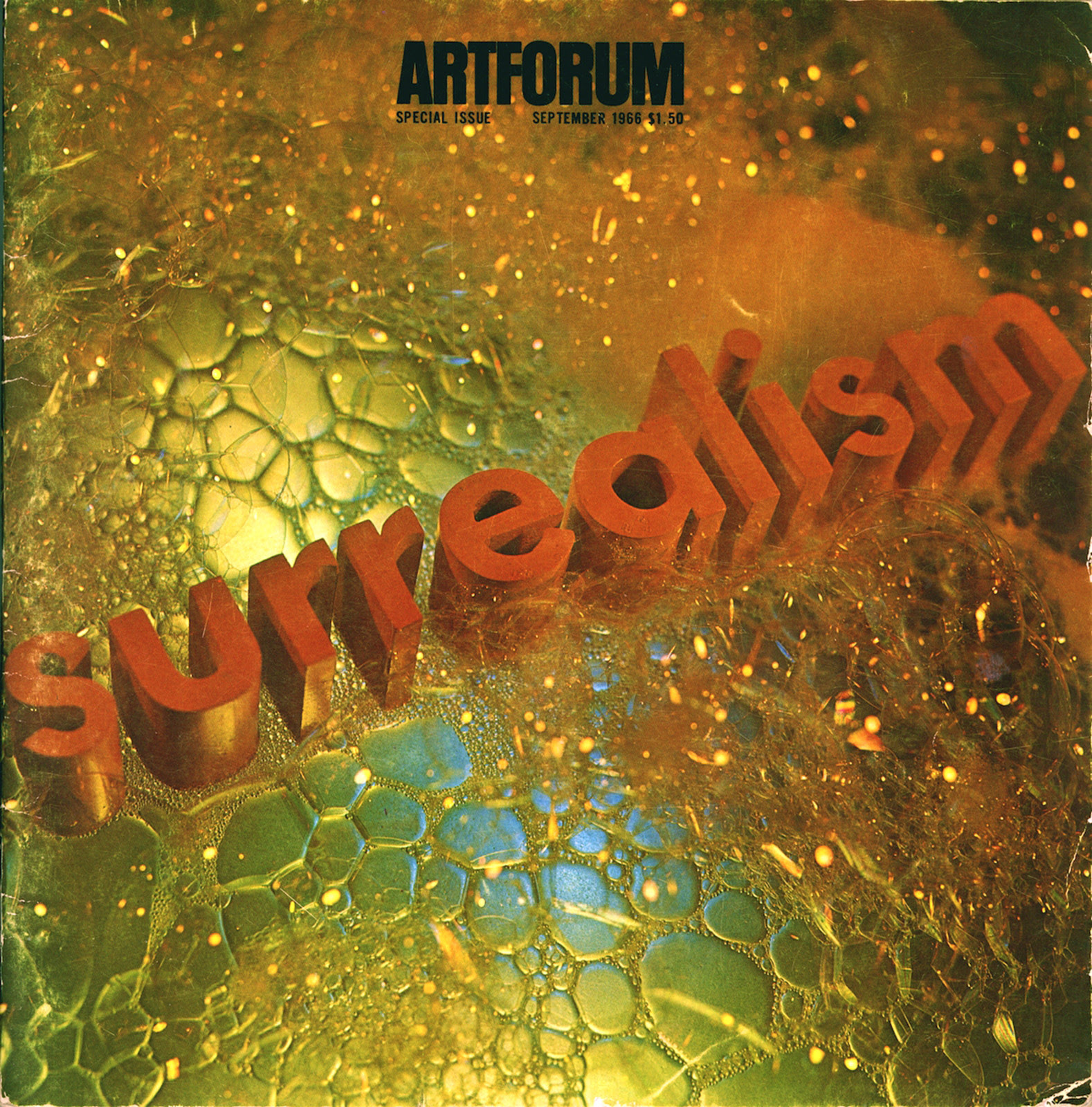

“Of all the decisive moments in the tradition of 20th century painting, only one can be said to burrow still relevantly within us, and to surface in ambitious works of art that show a sibling connection with the past.”—Max Kozloff, Artforum, September 1966

From the 1930s through the 1950s, scores of émigrés fleeing war in Europe—including Bertolt Brecht, Thomas Mann, Max Ernst, and Igor Stravinsky—briefly transformed Southern California into a center of world culture. They were drawn to Los Angeles not only by the balmy weather and the chance of working in Hollywood, but also by the critical mass of talent. But it wasn’t easy. In Exiles and Emigrés: The Flight of European Artists from Hitler, Lawrence Weschler put it this way: “How painfully incongruous must lazy palms on breezy evenings have seemed to people whose homeland was being bombed to smithereens.”

Courtesy Beatrice Wood Center for the Arts/Happy Valley Foundation.

Photo by Beatrice Wood.

“In the 1940s, an avant-garde scene emerged alongside the city’s commercial film industry.”

Surrealism was one of the artistic movements most disrupted by the events of World War II. Some of the displaced artists, such as Roberto Matta and Leonora Carrington, made fleeting appearances in Los Angeles; others, including Man Ray, Max Ernst, Dorothea Tanning, Marcel Duchamp, and Salvador Dalí, were more prolonged presences. But all of them had a dynamic effect on the region’s art, contributing the black humor and poetics of surrealism, the off-the-wall whimsy of pop culture, and a liberating strain of Dada that subverted hierarchic conventions.

While most of the European intellectuals—writers, musicians, composers, filmmakers, actors, critics, and theater directors—settled in Pacific Palisades and Beverly Hills, the surrealists gravitated to Hollywood. “It was like some place in the south of France,” Man Ray later wrote, “with its palm-bordered streets and low stucco dwellings. Somewhat more prim, less rambling, but the same radiant sunshine.” In fact, the artists’ choice was most likely influenced by the presence of Walter and Louise Arensberg and their extensive collection of advanced European modernism, which included masterworks of Dada and surrealism and served as the nexus for the artistic community of Los Angeles from 1921 to 1950. The Arensbergs had the largest collection in existence of works by Marcel Duchamp, including Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2), 1912. Duchamp, associated with both Dada and surrealism, made well-publicized visits to see the Arensbergs; a 1936 sojourn was documented by Beatrice Wood, who had founded and edited the Dada magazine The Blind Man in New York with Duchamp in 1917. Significantly, Duchamp’s first retrospective would occur not in Paris or New York but at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1962.

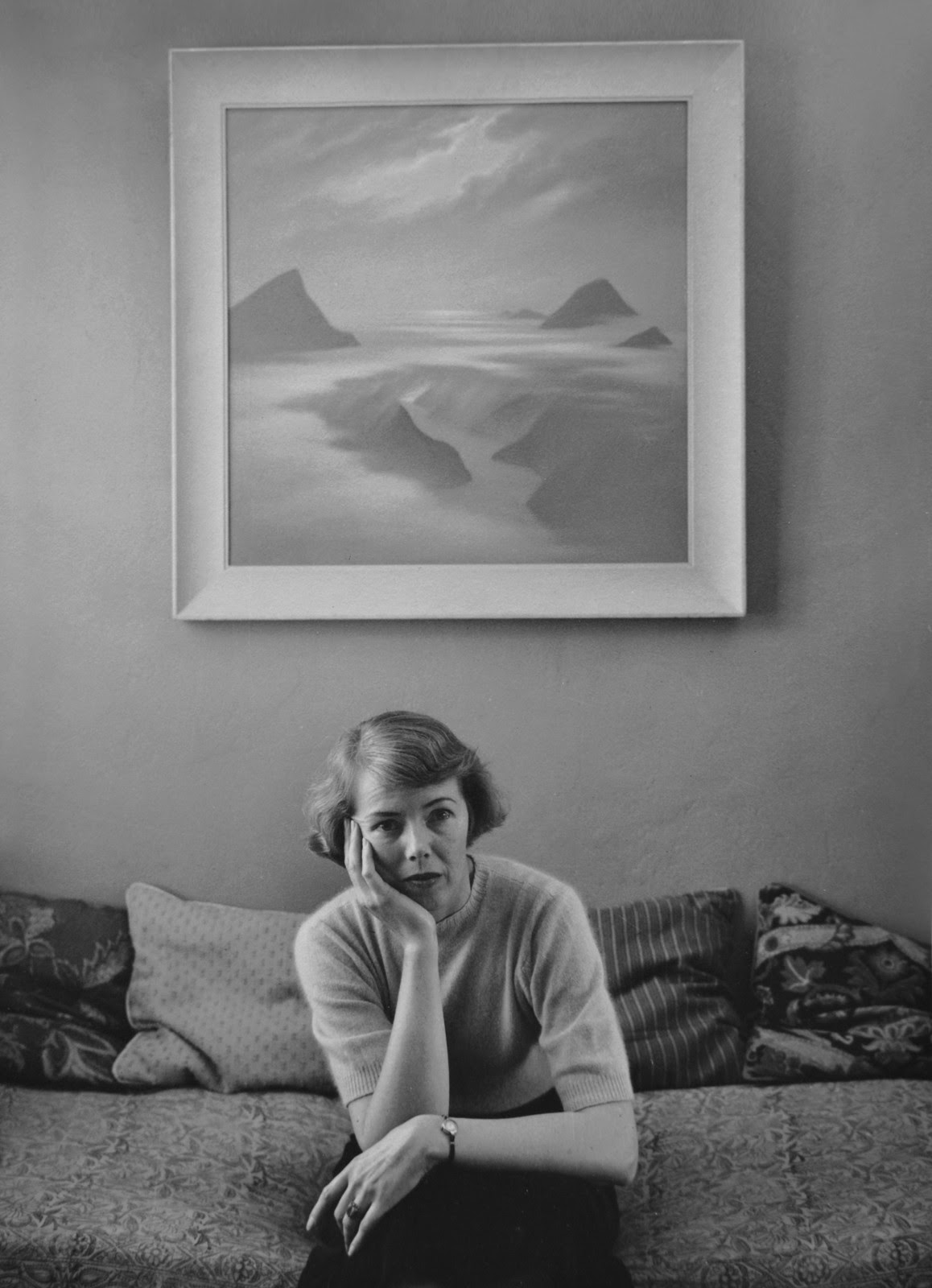

Photo by Florence Homolka.

Man Ray, a founder of New York Dada and a central figure in the Paris surrealist group, lived from 1940 to 1951 in Los Angeles, where the artist-dealer William Copley called him the “Dada of us all.” Reminiscing about his days there Man Ray recalled, “There was more Surrealism rampant in Hollywood than all the Surrealists could invent in a lifetime.” European Dada and surrealist artists who visited Southern California in the 1930s and 1940s felt both strangely at home and like fish out of water.

After escaping occupied France in 1940, Man Ray arrived in New York on the same ship as Salvador Dalí, then drove across the United States and took up residence opposite the Hollywood Ranch Market. According to his friend the abstract filmmaker Jules Engel, Man Ray “was thrilled to find that he could buy a bottle of good wine in the middle of the night for 99 cents that was the equal of anything he could buy in Paris.” Famous within Parisian culture, he struggled to make his way in Los Angeles; like other surrealists in town, he was disappointed that his ambitions did not pan out.

Nevertheless, Man Ray exhibited in museums and galleries, and lectured extensively on the West Coast, but he considered his 1948 exhibition at the Copley Galleries the high point of his California years. The guest list gives an idea of the artistic milieu of the time: Josef von Sternberg, Edward G. Robinson, Harpo Marx, Fanny Brice, Lorser Feitelson, Helen Lundeberg, Peter Krasnow, George Biddle, Hans Hofmann, Isamu Noguchi, Eugene Berman, Roberto Matta, Knud Merrild, Max Ernst, Dorothea Tanning, Igor Stravinsky, Aldous Huxley, Bertolt Brecht, Thomas Mann, Henry Miller, Luis Buñuel, Jean Renoir, and Otto Preminger.

During the 1930s and 1940s the Los Angeles avant-garde was encouraged by a loose network of intellectuals, curators, and collectors, but primary support came from short-lived commercial art galleries. Jake Zeitlin and Stanley Rose operated bookshop-galleries that were significant forces in the city’s cultural life, frequented by the likes of William Faulkner, Dorothy Parker, Dashiell Hammett, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. Rose operated the Centaur Gallery (later the Stanley Rose Gallery), a dynamic center for modernism beginning in 1934. In November of that year, Rose announced the First Western Exhibition of Surrealisme and Post-Surrealisme. This was the earliest showing of Lorser Feitelson and Helen Lundeberg’s Post-Surrealism, an American critique of European surrealism that awakened interest in the movement.Feitelson, Lundeberg, Lucian Labaudt, Merrild, Etienne Ret, and Harold Lehman were in the first exhibition; others later joining the group included Grace Clements, Philip Guston (then Goldstein), and Ruben Kadish. After a showing of the Post-Surrealists in Brooklyn, Alfred Barr Jr. included the work of Feitelson, Lundeberg, and Merrild in the seminal exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism at the Museum of Modern Art in 1936.

By 1950, along with John McLaughlin, Karl Benjamin, and Frederick Hammersley, Lundeberg and Feitelson would develop a type of abstraction termed hard-edge, or abstract classicism, which evoked a contemplative peace reflecting the artists’ absorption of Eastern philosophies. At the same time, it embodied movement and tension, expressing the mobility and artificiality of Southern California culture, thus presenting two directions found in contemporary Los Angeles art.

In 1936 and 1937, the West Coast dealer Howard Putzel, together with New York dealer Julian Levy, more significantly introduced European surrealism to Los Angeles, organizing shows of Yves Tanguy, Dalí, Joan Miró, and Ernst at Putzel Gallery in Hollywood. However, they failed to attract a following or to generate sales. Putzel moved to Paris in 1938 and befriended Peggy Guggenheim, whom he advised on purchases as she accumulated her significant collection of modern art.

Ernst and Dorothea Tanning were frequent presences on the art scene. In 1946, after they married in a double wedding with Man Ray and the dancer Juliet Browning, the Arensbergs threw a reception in their Hollywood home. At the time Tanning, who was key to the development of surrealism after World War II, had just designed the set for the Ballet Russe de Monte-Carlo’s Los Angeles production of Night Shadow, by Balanchine. Tanning also competed with nine other artists, including Ernst, Eugene Berman, Leonora Carrington, and Salvador Dalí to furnish a painting of the Temptation of Saint Anthony for The Private Affairs of Bel Ami, a film based on the novel by Guy de Maupassant, produced by Al Lewin, an art collecting film executive. Ernst won the highly publicized contest and appeared in the film.

During the late 1930s and 1940s, Dalí moved between the Monterey Peninsula, staying at the Hotel Del Monte, and the Garden of Allah in Hollywood, a fabled hideaway with bungalows surrounding a lotus-shaped swimming pool. Among the other residents were John Barrymore, F. Scott Fitzgerald, Katharine Hepburn, Ernest Hemingway, and Somerset Maugham. Drawn to California because of the promise of movie work, Dalí collaborated on projects with Harpo Marx, Alfred Hitchcock, and Walt Disney, among others. He had gotten a taste for film after working with Luis Buñuel on Un Chien andalou (1929) and L’Âge d’or (1930), where startling montage was a means of evoking dreamlike sensations.

In the 1940s, an avant-garde scene emerged alongside the city’s commercial film industry. Maya Deren’s Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), a collaboration with her husband Alexander Hamid made in their Los Angeles home, is one of the earliest and most influential American experimental films. The American Contemporary Gallery in Hollywood hosted screenings of films by Man Ray, Oskar Fischinger, James and John Whitney, and others. Marjorie Cameron, established within the city’s Beat community, appeared in Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome, and also exhibited graphic works and assemblages layered with esotericism.

Frederick Kann, a member of the Abstraction-Création group in Paris, moved to Los Angeles in 1940 and founded a series of seminal galleries and schools devoted to modern art. In 1944, he opened the Circle Gallery, an axis for a group that included Man Ray, Hans Burkhardt, Merrild, Ray Eames, Grace Clements, Hilaire Hiler, and Annita Delano. Kann himself experimented with automatism, exploring the fortuitous and unforeseen in abstract paintings. In 1948, along with actor-collector Vincent Price, the Arensbergs, and others, Kann founded the Modern Institute of Art, the first museum of contemporary art in the city. The opening exhibition included works by Marc Chagall, Joan Miró, Henri Matisse, and Duchamp. Although it had over fifty thousand visitors, the museum folded after fourteen months.

Copley Galleries, opened by William Copley in September 1948 in Beverly Hills, was fully invested in European surrealism. In his memoir “Portrait of an Artist as a Young Dealer,” Copley, who was also an accomplished painter later in life, wrote, “Surrealism made everything understandable: my genteel family, the war, and why I attended the Yale Prom without my shoes. It looked like something I might succeed at.” He organized exhibitions of René Magritte, Joseph Cornell, Yves Tanguy, Man Ray, Matta, and Max Ernst. The exhibitions were highly successful and helped to increase the visibility of surrealism in Southern California, but the sales were few; the gallery folded after six months. The final show was a retrospective for Ernst, whose paintings, in their phantasmagoric use of automatic drawing, tapped the unconscious and expressed the collective upheaval of the postwar period. However, there was a venomous critique in the Los Angeles Times: “To this reviewer the whole thing appears tired and it certainly tires him.”

Courtesy the Estate of William N. Copley.

Along with critical and commercial failure, surrealism also faced a conservative backlash, as censorship and the infiltration of Communism became urgent topics of discussion, especially in Los Angeles. In 1947 the Hollywood Ten—directors, writers, and actors who refused to cooperate with the anti-Communist hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee—were jailed for contempt of Congress and blacklisted by the film industry, creating an atmosphere of public distrust and fear in the arts community.

Not long after the Copley Gallery closed, another postsurrealist experiment arose, this time in San Francisco—the Dynaton group, consisting of Wolfgang Paalen, Gordon Onslow-Ford, and Lee Mullican. Before moving to the Bay Area in 1948, Paalen and Luchita Hurtado had been in Mexico for five years, brewing the dissident notions that coalesced into the Dynaton. As Mullican recalled, “Paalen felt that there was an intellectual climate in San Francisco where something could really happen. The war had ended. We were all enthusiastic that… this scene would be a growing center of culture.” However, soon after the 1951 San Francisco exhibition introducing the Dynaton, the group disbanded. Hurtado and Mullican married in 1954 and settled in Santa Monica. They continued exploring surrealism’s concerns with automatism and the inner mind, while practicing art making as a transcendental experience to open up higher planes of consciousness.

In the 1960s, a nationwide resurgence of interest in Dada and surrealism reverberated in Southern California. Duchamp had famously refused solo exhibitions of his work. Therefore, it was a remarkable occurrence when he agreed to his first full-scale retrospective, at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1962. Walter Hopps, who had visited the Arensberg collection frequently as a teenager, and cofounded the influential Ferus Gallery with Ed Kienholz in 1957, had joined the museum as curator the year before and was well-versed in Duchamp’s work.

On October 7 the art community of Los Angeles turned out for the black-tie opening, including Ferus Gallery’s stable of artists—Kienholz, Billy Al Bengston, Larry Bell, Robert Irwin, Edward Ruscha, and Ed Moses, as well as Andy Warhol, who was in town for a Ferus show of his own. Before Duchamp returned to New York, he was photographed playing chess in front of The Large Glass (or The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even) with the nude, twenty-year-old Eve Babitz.

The surrealist activity that began in Southern California during the 1930s culminated in 1966, when a Magritte retrospective, organized by the Museum of Modern Art, traveled to the Pasadena Art Museum. Concurrently, Artforum magazine, then based in Los Angeles, devoted an entire issue to surrealism, withEd Ruscha’s Surrealism Soaped and Scrubbed on the cover. While tipping his hat to the legacy of European surrealism, Ruscha also acknowledged its contribution to the pristine aesthetics of Los Angeles’s finish fetish and light-and-space art.

Susan M. Anderson, an independent curator and art historian, was formerly on the West Coast Advisory Board, Smithsonian Institution, Archives of American Art, and chief curator of Laguna Art Museum. Among her many publications is “Journey into the Sun: California Art and Surrealism,” in On the Edge of America: California Modernist Art, 1900-1950. University of California Press/Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, 1996.