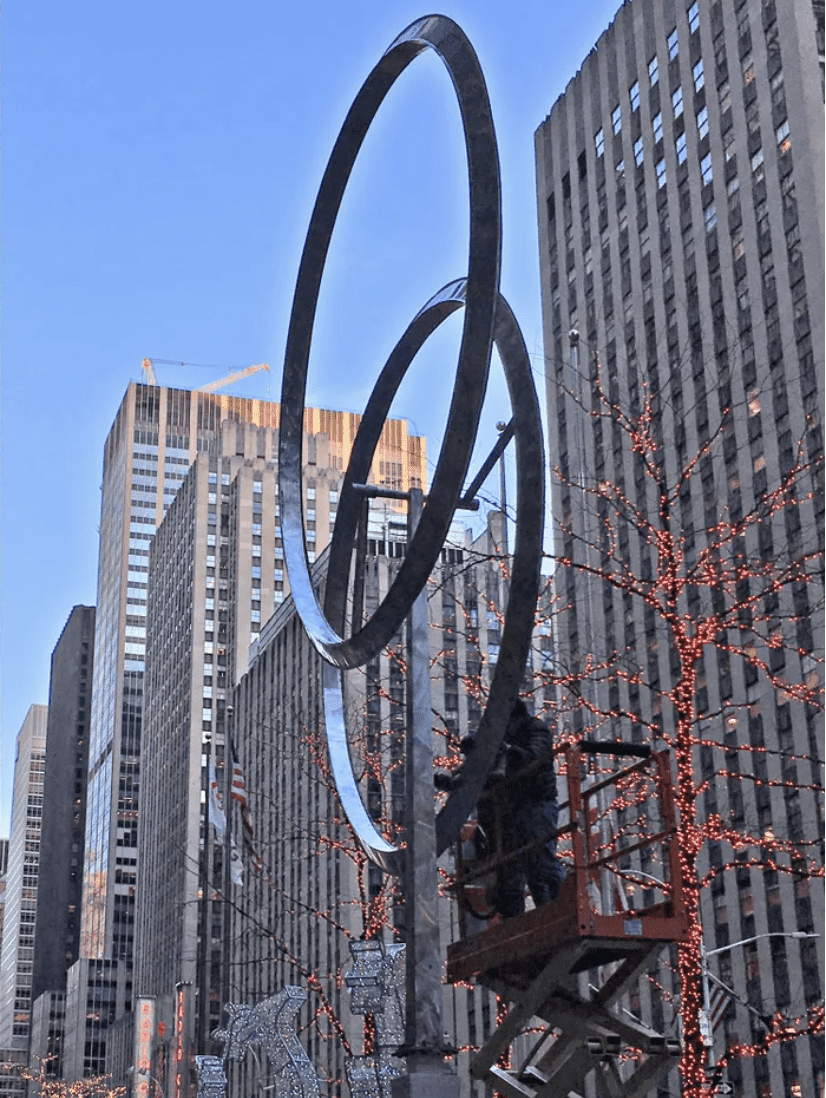

Behind every public sculpture is a story the public never hears. In December 2017—literally overnight—such a work appeared in New York at the busy corner of West 48th Street and the Avenue of the Americas. It was George Rickey’s Annular Eclipse, a giant pair of wind-powered stainless-steel circles, sixteen feet in diameter, held aloft by a post, thirty-five feet off the ground. Defying the steel-girded Midtown skyscrapers and holiday decorations bristling with colored lights up and down the avenue, the sculpture silently moved to its own timeless rhythms.

Installing a large sculpture in a dense urban setting is no simple matter; George Rickey knew that well, as did everyone who ever worked for him. The preliminaries can go on for months, but the actual installation, once the date is confirmed, must be meticulously timed and coordinated. With permits from the city at last in hand, the date was set—Wednesday, December 6—with a tight window. Work was to begin after 9 P.M., when the traffic died down, and be completed by 6 A.M. the following day. Installation would take twelve workers, nine hours, and approximately a hundred thousand dollars.

“Rickey was ultimately an artist for the public. His work was intellectually refined, but it was also eminently accessible.”

At the appointed hour, three parties convened on the site. Leading the effort was the team from the artist’s workshop, among them the artist’s younger son, Philip Rickey, along with a crew of veteran studio assistants. Machinery movers parked a seventy-five-foot tractor-trailer carrying the sculpture in pieces, with twenty sheets of plywood to protect the stone paving of the plaza, half a dozen sawhorses, three dozen packing blankets, and piles and piles of rope and rigging equipment, on the corner of 48th Street. Soon afterward arrived a four-wheel-drive forklift with extending boom, a scissor lift, and a motorized light stand with their operators. Meanwhile, half a dozen men hired by the office building stood by to oversee the safety of both the workers and the sculpture. A custom-designed plinth, awaiting the installation, was already embedded in the pavement of the small plaza.

After unloading the van, the workshop crew rested the pieces of the first circle on sawhorses and assembled it on the spot, using some five hundred screws and nuts in the process. “Space them out, start loose,” instructed Steve Day, who had almost fifty years of experience constructing and installing Rickey’s sculptures. Six handlers assembled the first circle in a little more than an hour. With the steady hand of the forklift driver and direction from the crew on the ground, they hoisted the post onto the plinth and bolted it down. Then came the most challenging and hazardous part of the job: lifting the circle into position, aligning it with the rotating arm, and sliding it into place. By the time they had completed this task, it was 3:30 A.M., and the second circle was yet to be assembled.

Working straight through the freezing cold December night, the team completed the job, with all the equipment removed, just under the wire-6:01 A.M. A city employee, known as the bolt checker, gave it the official green light. As the workday began and employees swarmed toward the building’s revolving doors, the circles danced silently above them, in gentle opposition to the vertical rise of the skyscraper behind them and the din of the morning traffic.

“He’s a sculptor who stands up to any urban situation,” said Philip Rickey, with the relief and exhilaration of a job well done, “and that’s rare.”

Until the installation, the sculpture had been very much at home in the country, rocking with the breezes in a hilly meadow just a few hundred yards from the workshop where it was made.

On a bright October afternoon a little more than a year earlier, media mogul Rupert Murdoch and his new bride, former supermodel Jerry Hall, ventured into the woods of Columbia County, New York. For Murdoch it was a nostalgia trip. He once had a weekend home in Old Chatham, and among its local pleasures for him was to drive over to East Chatham to visit George Rickey in his studio. At the time Murdoch, then married to Anna Maria Torv, was just one of Rickey’s many high-profile art patrons, such as Joseph Hirshhorn, S. I. Newhouse Jr., Carl Djerassi, Sir Peter Palumbo, and Nelson Rockefeller, and museum directors including Alfred Barr, of the Museum of Modern Art, Carter Brown, of the National Gallery, and Thomas Messer, of the Guggenheim Museum, to visit East Chatham in view of adding a Rickey sculpture to their collections.

“Through the door that Calder opened Rickey ventured on, adding sophisticated engineering and a multitude of forms to the basic idea of moving sculpture while reducing the concept to a study of movement itself.”

A hundred and thirty-five miles north of New York City, where the Berkshire Hills meet the Hudson River Valley, an area long ago settled by farmers cultivating fields of rye for horses and now almost completely forested, land in 1957 was cheap, and so was the dilapidated farmhouse that George Rickey and his wife, Edie, bought that year. George adapted the tumbledown chicken barn as his studio, laying wooden boards over the dirt floor and installing electricity and a woodstove for heat. The house was so cold in winter that they took the cats to bed with them to keep warm.

Over the years they modernized the house and, as they were able to, acquired adjacent land and buildings along County Route 34. They cleared trees and dug ponds all over the property, creating the setting for a constant and ever evolving exhibition of Rickey’s outdoor sculptures throughout the seasons. They engaged staff to support every aspect of the operation, from outdoor maintenance to skilled and unskilled studio assistance and from business accounting to sales.

In its heyday, the Rickey workshop was its own little empire in the woods. In that quiet corner of Columbia County, it was a scene of constant motion-of staff coming and going and of multiple sculptures under construction and arrayed around the property, rocking, and playing to the wind.

After Rickey died, in 2002, the house remained furnished but uninhabited. Much of the land was sold off, while a skeleton staff continued to work on the grounds and in the workshop. By the time Murdoch and Hall came by in 2016, there were just a few sculptures scattered around what was left of the estate.

The couple’s intention had been to add to their private art collection in Los Angeles, but Murdoch abruptly changed course when he caught sight of Rickey’s last major work, the spectacular Annular Eclipse. In a high field with a view of the Taconic Range in the distance, a pair of stainless-steel circles focused the view of the distant hills like an enormous lens. Murdoch was now envisioning his Midtown office building in the heart of corporate America: “It’s going to stop traffic,” he predicted gleefully. Officially handling estate sales since 2009, Marlborough Gallery brokered the deal, and the sculpture was Murdoch’s in time for Christmas.

While permits for its installation were under review at New York’s City Hall, another process was in the works upstate. Studio assistants dismounted the sculpture from its post in the field, took it apart, changed all the hardware and the ball bearings of the rotating arms, and cleaned away the moss that had gathered over eighteen years in its natural setting.

In a major historical survey of American sculpture at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1976, Rickey was hailed as “the major spokesman of kinetic art.” His work was by that time well known. His duets and trios and quartets of moving blades, planes, and circles were prominently displayed in museums and public parks and at college campuses and corporate headquarters around the world. When he died, the New York Times called Rickey “one of two major twentieth-century artists to make movement a central interest in sculpture. Alexander Calder, whose mobiles Mr. Rickey encountered in the 1930s, was the other.”

Although Rickey’s work would forever be associated with Calder’s, it was unmistakably his own. Calder opened the door, he would say, but he soon wondered “if Calder had said it all.” Through the door that Calder opened Rickey ventured on, adding sophisticated engineering and a multitude of forms to the basic idea of moving sculpture while reducing the concept to a study of movement itself. While Calder’s colorful mobiles bobbed and turned, Rickey’s kinetic sculptures achieved complete rotation, multiple variations of the pendulum, and the disturbing, joyride effects of conical movement. He produced more than three thousand works, from small indoor pieces for the private collector to hundreds of major outdoor installations.

Rickey was ultimately an artist for the public. His work was intellectually refined, but it was also eminently accessible. It called attention to itself, but even more than that to the atmosphere around it. It sculpted the air with its movements; it defined the invisible wind. Nature, Rickey would say, was not his subject; it was “a partner or collaborator.” His mature work, constructed of cool geometric forms in monochrome stainless steel, is deliberately lacking in imagery of any kind. It was the shape of its movement that mattered, he said, and that was all. As Hayden Herrera wrote in 1985, Rickey “explores a counterpoint of visible and invisible geometry in constructions that are as simple and straightforward as Shaker tools, but as mysterious in their implications as God’s compass in medieval images of Genesis.”

Despite Calder’s example, Rickey discovered at an early stage of his journey that he was “working in a rather lonely idiom,” but for a period in the 1960s he found company in that lonely field in great variety, joining a younger generation of mostly European artists in a quest to break away from the dominance of postwar painting. At that point he became a defining figure in what the artist Hans Richter coined the “movement movement.” He was center stage in a wild ride, a pillar of reason and rationality amid a mad decade. Perhaps more succinctly than any other artist of his time, Rickey articulated a late-Modernist convergence of equal parts art and science. Yet while his work enjoyed many years in the limelight, his unique contribution to the vocabulary of modern abstract sculpture has dwelled in the shadier groves of modern art history. He was highly informed and actively engaged in the art world of his time, but in the long run, he was a lone star in a galaxy of overlapping and conflicting trends.

Though much has been written about Rickey’s work in sculpture, little has been studied of his life and career in the wider context of the twentieth-century art world and the leading figures and movements through which he navigated—from his student days at the Ruskin School at Oxford to Paris in the 1920s, from Depression-era America to the disruptions of World War II, from the rise of New York as the world’s art capital at mid-century to the tumultuous 1960s, when he first emerged as an international figure. His sculpture, always an expression of balance and tension, uneven structures, and counterweights at play with one another, also expressed, though he never said so, the dual forces of his personality and personal relationships in abstract form.

He was fond of citing the mythological figures of his classical education by way of explaining the twists and turns of his life. “Chance, quite possibly, outweighs inspiration in an artist’s life,” Rickey admitted in the heyday of his success. “The Greeks invoked the Muse, but there was also Fortuna.” He considered himself at least as fortunate as he was inspired. As deliberate as Rickey was by nature, he also actively embraced the role in his life of chance. Chance was integral to his wind-powered sculpture, but so was Fate in its limitations. Another ancient myth he was fond of citing was that of the three Fates of Roman mythology: three old women weavers-one who spins, one who measures, and one who cuts.

At the measuring stage of Rickey’s career, in the late 1940s, when he turned from painting to sculpture, his second marriage, to his much younger wife, the vivacious Edith Leighton, made for a power couple soon to well known in the art circles of New York, New Orleans, Berlin, and Los Angeles. In the full-time management of her husband’s career and reputation, Edie was the exemplary womanbehind-the-man of her era. Many would say that he would not have achieved his success and fame without her devotion as his tireless executive secretary and unforgettable hostess. She towered over him physically at her full six feet and overshadowed him socially as the artist’s wife.

Successful as it was, their collaboration was not without conflict. As Rickey’s popularity accelerated in the 1970s and a growing number of assistants joined him in his upstate New York workshop, the innocence and adventure of earlier days was lost in the headlong race to meet the demand for his work, and the strain on his marriage and family emerged in the background of his well-managed public profile.

Fortunately for us, both George and Edie Rickey were masters of the dying art of personal letter writing. From the time he learned to write to his final halting days, George penned his thoughts, impressions, opinions, worries, and emotions to his friends and lovers and his wife and family. We can read, therefore, in real time rather than in retrospect what he witnessed and experienced in clear, complete sentences, with a richness and immediacy nonexistent in any other form. Edie, also a voluminous correspondent, created a flowing action-packed newsreel down to the last detail with generous helpings of humor and emotion. When George and Edie were separated by oceans and continents, they volleyed air letters back and forth like two private diaries in conversation, with their differences of character along with their mutual devotion to the cause in high relief.

This is the story of an American artist who was never entirely American, a sculptor who was for many years a painter, an artist who was at least as much a teacher, a critic as well as an historian, a man who in all his ninety-five years never really settled down. Rickey was ambidextrous, literally, and metaphorically. The grandson of a judge on one side and a clockmaker on the other, it was his two sides-one that creates while the other observes, one that stands by while the other takes off—that made his sculptures a riveting study in balance. This is a story of a life style as much as a life, of a marriage as well as a man.

What are the origins of an artist’s inspiration? What encourages the artist to strike out on his own, to reject the safer worlds of the more traditional vocations? It is only in retrospect that the artist, or we, can say. In Rickey’s early years, it was the tinkle of glass wind chimes over a neighbor’s door, the anvil of the blacksmith shoeing a horse, the crank of a casement window, the pedal of a sewing machine, and the stiffening of a sail in the wind. “Childhood,” he wrote at the other end of his life, “is a time of discovery. The ‘second childhood’ of the elderly is, in art, still a time of discovery-something new every day, not only between the front door and the garden gate, as Emerson saw it in Concord, but at the point of the burin, at the contact of the brush with the canvas, or the blade of the chisel with wood or stone, or now, the torch cutting steel, the wheel grinding away metal. These combat areas are not for children; they are where the battle’s lost or won, and where all the resources of a lifetime are thrown into the fray.”