On occasional Saturday mornings, Kasmin shares essays and interviews that expand critically on the work and practice of the gallery artists. Concurrent with Out of an Impasse: Bronze Sculptures by Max Ernst, 1934-1973, a newly published online exhibition, The Kasmin Review is celebrating a near decade since the gallery’s landmark 2015 exhibition Max Ernst: Paramyths, Sculpture 1934-1967, the artist’s first major solo presentation of sculptures in North America since 1993. Below, curator Michele Wijegoonaratna examines Max Ernst's sculptural output between 1934 and 1967 to reveal how his approach to sculpture informed his painting. She questions the long held belief that Ernst turned to sculpture as a means of diversion and play and asserts that sculpture was integral to his artistic development. Originally published on the occasion of the exhibition, this essay first appeared in Max Ernst: Paramyths, Sculpture 1934-1967, exh. cat. (New York: Paul Kasmin Gallery, 2015), 4–10.

Die Kunst mag ein Spiel sein—aber Sie ist ein ernstes Spiel.

Art may well be a game—but it is a serious game. [1]

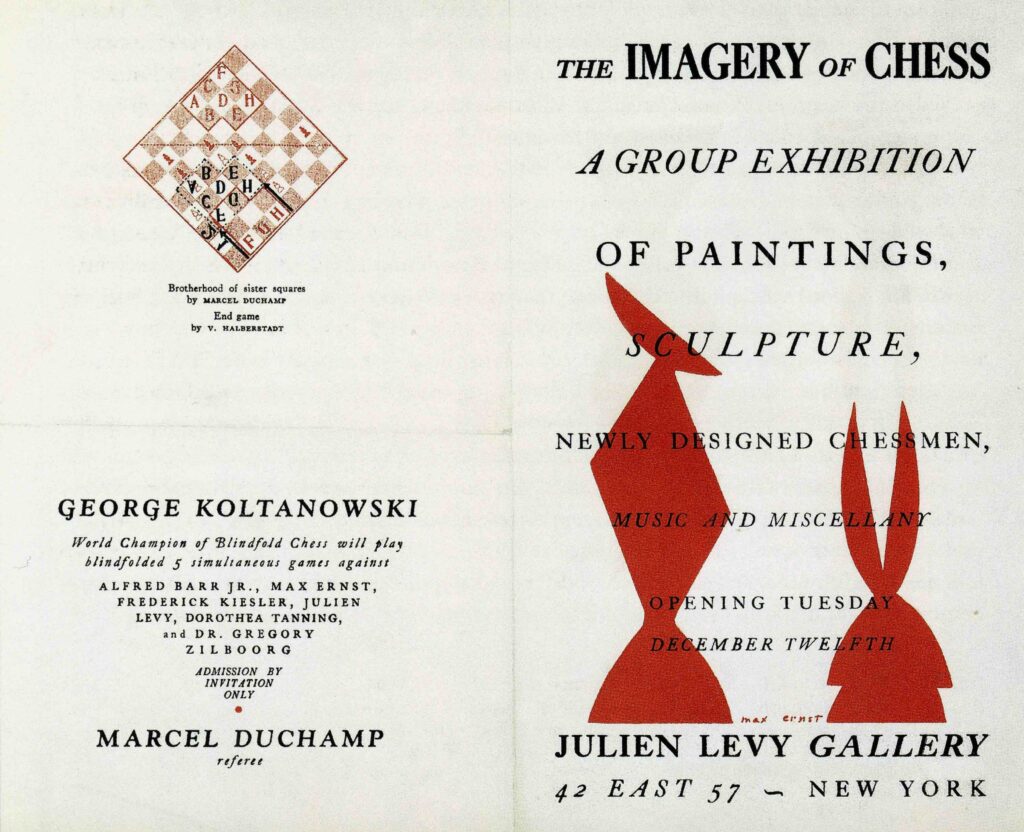

In the summer of 1944, Max Ernst sent a postcard to his dealer Julien Levy with a laconic message: “No chess set available at the village store.”[2] Ernst and his artist wife, Dorothea Tanning, had rented an old house on the cove of Great River, Long Island for the season, which they were to share with the dealer for the purpose of relaxing and swimming. However, as Ernst reported later, “there were so many mosquitos there we could not stick our noses out of doors, so I decided to take over the garage, screen it and make a studio out of it. I worked the whole summer there on sculpture.”[3] As Levy remembered it, “Max had become completely diverted from painting. He was making a chess set and a large sculpture he called The King Playing with the Queen…Max had taken over the garage as a studio and there he poured his plaster of Paris into ingenious molds.”[4] Both Levy and Ernst made chess sets that summer and their enthusiasm for the game and the energy Ernst devoted to creating sculptural chess pieces as well as other, large, sculptures such as Jeune homme au cœur battant (1944) and Jeune femme en forme de fleur (1944) resulted in a groundbreaking exhibition in Levy’s gallery that December titled The Imagery of Chess for which Ernst designed the striking announcement quarto. Levy invited 32 artists, one for each of the chess pieces on the board, to design their own sets. The roster of artists included Calder, Duchamp, Matta, Motherwell, Noguchi, and Tanning, but it was Ernst whose reductively elegant chessmen were singled out by the press as “the most interesting” and “both exciting and satisfying…creative embodiments of their functions.”[5] Ernst’s chess pieces were rendered from shapes found among old tools in the garage and from kitchen utensils. They were, as Werner Spies has pointed out, marked by a sheer simplicity and lucid contours that reflected a new vocabulary of sculptural form.[6]

Ernst had turned to sculpture with intense bursts of creativity at various moments in his career, most notably from 1934, when he spent the summer with Giacometti in Majola, Switzerland, where he famously reworked boulders that both artists quarried from the Forno glacier. “Alberto and I have caught the sculpture fever,” he wrote to the art historian Carola Giedion-Welcker.[7] The year before he took a studio close to Giacometti’s and created nine, important, free-standing sculptures including La belle allemande (1934/1935), Oedipe I (1934), and Habakuk (1934), biomorphic works that employ casts from found objects such as flower pots and seashells and embody the techniques of stacking and assemblage to form a three dimensional response to his established innovations with collage. Nevertheless, it was the summer of 1944 that marked a watershed and crucial reorientation in Ernst’s sculptural œuvre, one that resulted in a new approach to objects that as Lucy Lippard has remarked, reflect a “strong visual logic that verges, at times, on the nonobjective.”[8] However, at any moment in his career, Ernst’s sculptures are neither truly abstract nor obviously figurative in nature, but often an enigmatic combination of both. This is most evident in Jeune homme au cœur battant (1944) where a few simple geometric abstracted forms elicit the concave head and scooped out heart of the man whose armless torso lurches forward to suggest an animated figure.

Whenever I reach an impasse in my painting, which happens time and time again, sculpture always offers me a way out. —Max Ernst

The significant innovations Ernst made as a painter and printmaker that include the inventions of frottage, grattage, decalcomania and a radical oscillating drip technique in works such as Young Man Intrigued by the Flight of a Non-Euclidean Fly (1942/1947) that prefigure Jackson Pollock, often eclipse a critical engagement with his sculptural œuvre. As if his sculpture were a whimsical diversion rather than a serious artistic endeavor. Ernst himself is largely to blame for this misconception. In an oft-quoted statement made to the filmmaker Peter Schamoni, the artist once said of his sculpture: “Sculpture is more pure play than painting. With sculpture both hands play a role, just as it does when making love…”[9] And, in a separate interview he noted: “Whenever I turn to it, I feel that I am on holiday…with sculpture I can relax. I enjoy it the way I enjoyed making sandcastles on the beach when I was a boy.”[10] These abbreviated statements, taken out of context, should not indicate that Ernst viewed sculpture as an inconsequential game or mere vacation dalliance. This is made clear by the seldom quoted preface to the Schamoni conversation in which Ernst says, “Whenever I reach an impasse in my painting, which happens time and time again, sculpture always offers me a way out.”[11] For Ernst, therefore, sculpture may have been a means to overcome “painter’s block.” In this sense, his sculpture was integral to his artistic development as a painter and enabled him to work out intellectual issues in his work as a whole. Ernst sculpted like a painter. His approach to sculpture was additive not subtractive, based on a technique of finding, assembling, recombining and then casting found objects first in plaster and only much later in richer, more durable materials such as bronze.[12] His methodology underscores his sculpture’s inextricable connection to his painting and collages where an underlying flat support is transformed by layers of paint to create form. Recognition of this particular relationship between sculpture to painting and the relative merits of each is not new. It dates back to the paragone debates of the Renaissance. In defining the nature of sculpture, Michelangelo once said, “By sculpture I mean the sort that is executed by cutting away; the sort that is executed by building up resembles painting.”[13] Ernst’s deep knowledge of the art historical tradition would have included an awareness of the unresolved tension between sculpture and painting and the historic rivalry between these arts. Evidence for this in his work comes as early as 1919 in a painted wooden relief titled Fruit d’une longue experience in which he incorporated the words “art” and “sculpto-peinture” into the piece in direct and probably ironic reference to Archipenko’s series of Medrano sculptural paintings, but also in recognition of the complex relationship between the two media.

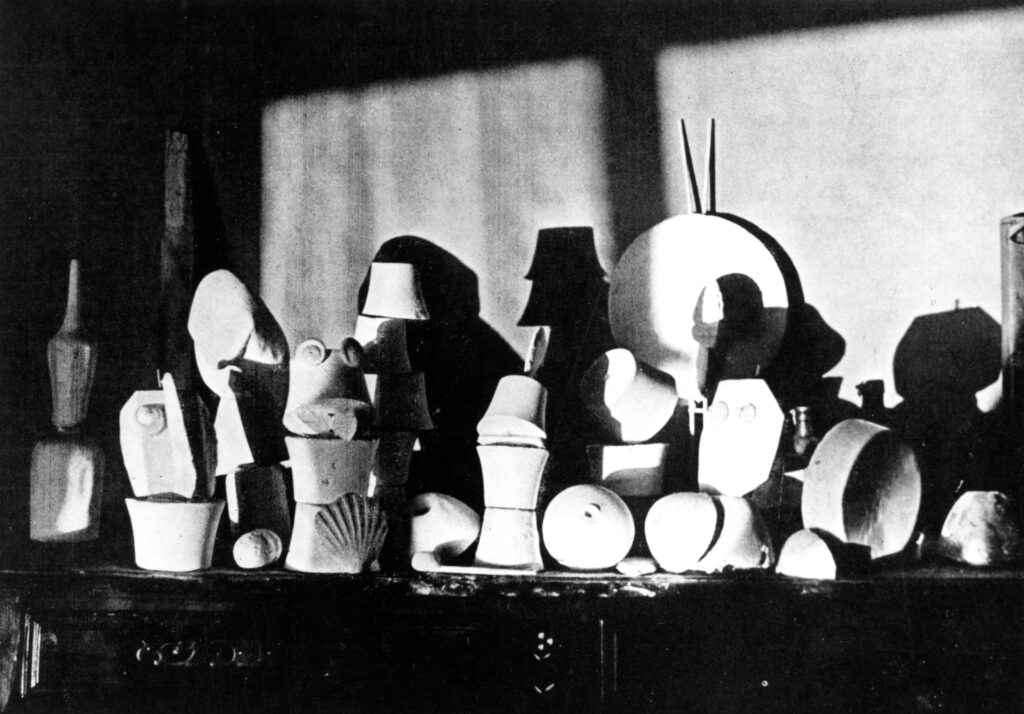

In 1935, the artist staged a photograph of assembled and found objects on a table in his studio titling the image Jeu de constructions anthropomorphes (unfinished sculpture). The photograph not only functions as an art object in itself, but also displays several plaster casts of the found objects that Ernst used in the sculptures he made before the summer spent with Giacometti including the round disk and shell for La belle allemande, the flower pots for Oedipe I and the shell that would reappear in sculptures from Huismes such as Dream Rose (1959) and Bosse de nage (1959). Though he referred to these sculptures as “Jeu de constructions,” which on the surface would seem to be a contradiction in terms since play often indicates the opposite of formal composition, it is worthwhile to interpret the word “jeu” (play) as indicative of chance and freedom rather than as fun or folly.

Ernst’s approach to sculpture is very much in keeping with Huizinga’s 1938 treatise on play, Homo Ludens, in which the cultural theorist posits the notion that play is not only capable of being a serious endeavor, “for seriousness seeks to exclude play, whereas play can very well include seriousness” but that play is also an interlude in human reality, “a temporary activity satisfying in itself and ending there.”[14] Ernst’s intense engagement with sculpture at distinct moments throughout his career, where he was utterly and earnestly absorbed by the pursuit, is a testament to these ideas. Art, like play, is autotelic created as an end in itself as opposed to handicraft, which works to produce something for a purpose. With the exception of the chess pieces whose ultimate function were to be used in a game, Ernst made sculpture purely out of a necessity to spur his artist creativity. Ironically, he prefaced the aforementioned quote about sculpture being a form of relaxation by saying, “Painting is like chess: you have to give your whole mind to it. You live in a state of concentration that is almost unbearable.”[15] Chess, as Huizinga notes, while ostensibly a game is played in “profound seriousness”[16] and it is therefore illuminating that Ernst’s first free-standing modeled sculptures were the chess pieces he created in 1929 in the Paris studio of the ceramicist Artigas, and that he again returned to making chess pieces in Great River in 1944. The seriousness of chess becomes a metaphor for the importance of sculpture, particularly if we consider the prominence of The King Playing with the Queen (1944) in his œuvre. The dominant King with his concave body and horn shaped head whose arm encloses the more diminutive queen dominates the chessboard and yet unlike the queen who has her entire body to move freely around, the King has been severed at the hip leaving him motionless and metaphorically vulnerable. The couple is hieratic and invokes dignifying memories of past, classical styles that anticipate Ernst’s majestic cement sculpture Capricorn (1948) that adorned the home he shared with Dorothea Tanning in Sedona, Arizona and whose iconography would reappear in the next decade in the works of other artists such as Henry Moore’s King and Queen (1952/1953). Julien Levy was deeply impressed by the sculptures that Ernst created during the summer of 1944 and American critics concurred, with Clement Greenberg writing in a review that “Max Ernst shows himself to be an immeasurably better sculptor than painter.”[17] One of the people who took Ernst’s sculptural output very seriously was Robert Motherwell who said in a letter to David Hopkins:

My real rapport with Ernst began […] when I was one of the few people who responded deeply to his sculpture. When I first saw them in his studio, I was thunderstruck. I remember his face turning red with anger and saying in effect “don’t make fun of me.” When asked why he would say that, he would say, “no one likes them.” [18]

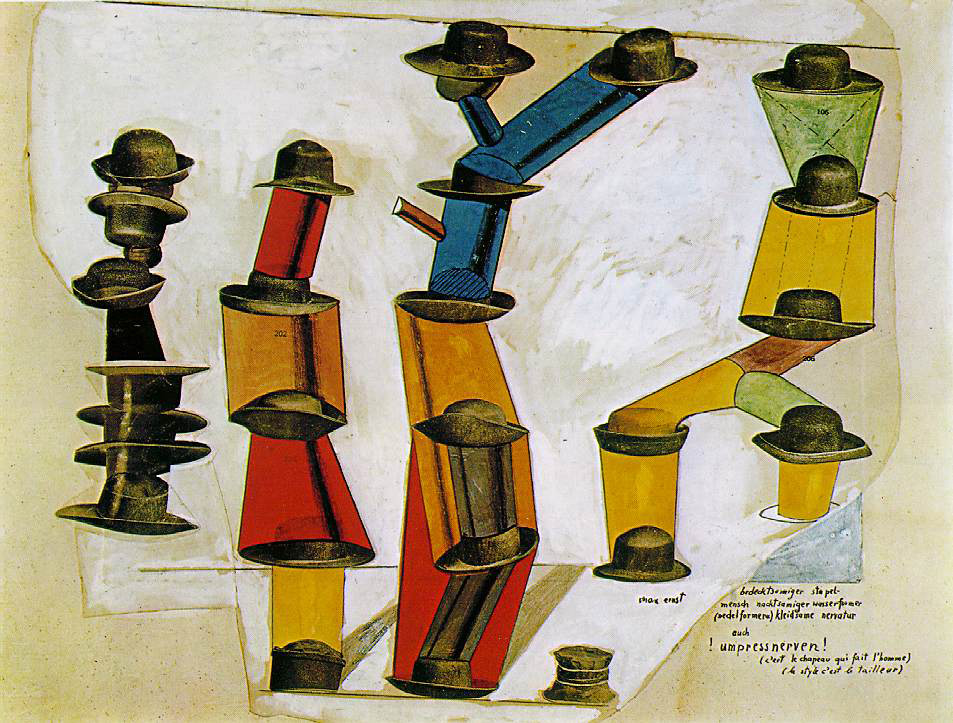

Ernst responded so positively to Motherwell’s interest in his sculpture that he insisted on giving the artist The King Playing with the Queen, which Motherwell recalled was “an extreme act of generosity on his part [and] revealed among other things a real insecurity and therefore an inordinate gesture in response to my obviously genuine admiration.”[19] This anecdote would seem to confirm that, for Max Ernst, sculpture was thus neither an act of dilettantism nor a mere means of passing the time. Evidence for this comes as early as 1936 when he published a theoretical treatise about his work titled Au-delá de la peinture (Beyond Painting) in which his narrative did not discriminate between painted and sculptural works.[20] When Ernst refers to his sculpture as a “jeu de construction,” it also indicates how closely his sculpture relates to collage whereby he takes existing forms and recombines them to create a new reality. This is certainly the case in Oedipe I, but also in L’imbécile (1961). The precariously balanced structure of Oedipe I and the swaying duality of Âmes-sœurs (1961) are justifiably related to Ernst’s famous 1920 collage The Hat Makes the Man with its sexualized staggered array of hats.[21] More importantly, there is a constant dialogue between Ernst’s sculpture and his painting. This is particularly true of the works that he made in Huismes.

Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY.

In 1959, 1960 and 1961 Ernst was intensively working on sculpture again. He made about 11 sculptures that, with the exception of Êtes-vous Niniche? (1955/1956) and Deux et deus font un (1956), which were created in the mid 1950s, are the first works that were cast into bronze the year that they were created. The painting L’illustre forgeron des rêves (1959) depicts a bestiary of creatures whose grinning features reference similar beings in Sous les ponts de Paris, L’imbécile (1961) and the facial expressions of Âmes-sœurs (1961). On the left hand side of the painting is the round, applied face and body of Apaisement (1961) as well as the round google-eyes evident in several of the sculptures from this time including Bosse de nage.[22] Similarly, Apaisement (1961), the only work whose texture is a painterly surface, responds materially to Ernst’s paintings.

The elements of play as outlined by Huizinga bear an affinity with Ernst’s sculptural practice: Huizinga stresses that play is freedom and does not accord with real life, an idea that harks back to Kant who, in his Critique of Judgment views art and play as occupations that are agreeable on their own account.[23] Play also has a constant element of tension that needs to be resolved whether it is a game such as chess or a child catching a ball. The back and forth between tension and solution has much in keeping with Ernst’s sculptural endeavor. Finally, play creates order because there are rules and any deviation from play spoils the game. For Huizinga, “the profound affinity between play and order is perhaps the reason why play seems to lie in the field of aesthetics.”[24] It is well known that Ernst had an interest in mathematics and non-Euclidean geometry, a fascination that he shared with Man Ray. In 1950, Ernst painted Euclid and in response to Man Ray’s Surface de Kummer a seize points doubles don’t huit reels (1936) created two paintings with sculptural elements Printemps à Paris (1950) and La religieuse portugaise (1950).

[Ernst’s] sculpture was integral to his artistic development as a painter and enabled him to work out intellectual issues in his work as a whole. —Michele Wijegoonaratna

When viewing Ernst’s sculpture, therefore, we must not confuse a sense of play with a lack of restraint and we must take into account the artist’s wicked sense of humor and mischief and the sheer enjoyment that resulted from his engagement with sculpture. There is often a salacious wit to his pieces, the lascivious smiles that play on the open mouth of Oedipe I and L’imbécile, the latter of whom, on closer inspection, has the body of a priest with a clerical collar and the head of a fool. The humor also plays out in the gentlest of ways with works such as Dream Rose (1959) a fond and whimsical rendering of his favorite Tibetan dog, but also in a sophisticated manner in works such as Êtes-vous Niniche? In this work, Ernst has taken a found object of rural life, the ox-yoke, and positioned one on top of another separated by a bar. The pedestal for the work is a printer’s block with the word Niniche reversed and print ready. The exact meaning of the sculpture is unclear, but it functions as a portrait bust. Interestingly, Niniche was a well-known vaudeville theater piece performed in Paris in 1878. It was translated into German and also found its way to the stage in London and was shown in New York by 1885.[25] It was a burlesque tale of a Parisian cocotte who married a Polish count under false pretenses and was forever “yoked” to her social deception and the fear of her true identity being discovered. The play, which was made into a silent black and white film in Germany in 1925, was immensely popular and may well have been known to Ernst. In Êtes-vous Niniche?, Ernst engages with gender stereotypes that also emerge in the lean masculine, vigorous form of Jeune homme au cœur battant which finds its counterpart in the feminized round, passive form of Jeune femme en forme de fleur and the plumpness of Apaisement.

Ernst always loved women and, as Dorothea Tanning wrote, “Max Ernst drew the magic formula for making women what he wanted and what they wanted to be: symbols of grace.”[26] In 1967, Ernst created an elegant homage to his wife, Dorothea Tanning, in La plus belle. She is a study in contrasts. Her slender, sinuous body bent slightly at the waist and tilted, smiling, abstracted face is smoothly rendered but set upon a roughened base that, as Jürgen Pech points out resembles the tail of a Nereid or mermaid and relates to Ernst’s conception of himself as Poseidon. The work, both regal and playful at once is a testament to Ernst’s serious passion for Tanning and perhaps the closest embodiment of his observation that “sculpture emerges in an embrace, two handed, like love.”[27]

Originally published on the occasion of the exhibition Max Ernst: Paramyths, Sculpture 1934-1967, Paul Kasmin Gallery, New York, 2015. Click to purchase from Kasmin Books.

IMAGES

A Painter at Play? Max Ersnt and the Serious Side of Sculpture © Michele Wijegoonaratna.

All artwork by Max Ernst © 2023 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / ADAGP, Paris.

Exhibition brochure by Marcel Duchamp © Association Marcel Duchamp/ADAGP, Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

NOTES

1. Caspar David Friedrich, letter to Philip Otto Runge, Dresden, October 4, 1808. Reprinted in Philipp Otto Runge and Johann Daniel Runge, Hinterlassene Schriften, vol. 1 (Hamburg: Verlag von Friedrich Barthes, 1840), 365.

2. Julien Levy, “A Summer with M.E., 1944,” in Memoir of an Art Gallery (1977). Reprinted in Larry List, ed., The Imagery of Chess Revisited, exh. cat. (New York: Isamu Noguchi Foundation and Garden Museum, 2005), 147.

3. Quoted in “Eleven Europeans in America,” MoMA Bulletin 13, no. 415 (1946): 2–31.

4. Levy, “Summer with M.E.,” 147.

5. Kenneth Harkness, “Chessmen of Tomorrow” Chess Review (January 1945): 3; G.J., “Presenting the Imagery of Chess,” Art Digest (December 15, 1944): n.p. Both reviews reprinted in List, Imagery of Chess.

6. See Werner Spies, “Sculptures, Houses and Landscapes,” in Werner Spies: The Eye and the Word; Collected Writings on Art and Literature 3: Max Ernst: From Material to Style (New York: Abrams; Berlin: Berlin University Press, 2011), 126.

7. Reinhold Hohl, Carola Giedion: Welcker Schriften 1926-1971; Stationen zu einem Zeitbild (Schauberg: Verlag M. Du Mont, 1973), 508.

8. Lucy Lippard, “The Sculpture,” in Sam Hunter, ed. Max Ernst: Sculpture and Recent Painting, exh. cat. (New York: The Jewish Museum, 1966), 37.

9. Max Ernst, quoted in Peter Schamoni, Max Ernst läßt grüßen: Peter Schamoni begegnet Max Ernst (Münster: Coppenrath Verlag, 2009), 105.

10. Ernst, interview with Patrick Waldberg. Quoted in John Russell, Max Ernst: Life and Work (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1967), 205.

11. Ernst, in Schamoni, Max Ernst, 105.

12. Most of Ernst’s sculptures were first created in plaster of Paris. It was not until the mid to late 1950s that the artist had the financial resources to cast in bronze.

13. Sven-Olov Wallenstein, “Space, Time and the Arts: Rewriting the Laocoön,” Journal of Aesthetics and Culture 2 (2010).

14. Johan Huizinga, Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play Element in Culture (Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publishing, 2014), 45, 9.

15. Ernst, interview with Waldberg. Quoted in Russell, Life and Work, 205.

16. Huizinga, Homo Ludens, 6.

17. Clement Greenberg, “Review of Exhibitions of Mondrian, Kandinsky and Pollock; of the Annual Exhibition of American Abstract Artists; and of the Exhibition European Artists in America,” The Nation (April 7, 1945). Reprinted in John O’Brian, ed., Clement Greenberg: The Collected Essays and Criticism 2: Arrogant Purpose 1945-1949 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 17.

18. Extract from a letter by Robert Motherwell to the English student, David Hopkins. Unedited typescripts, June 1987, courtesy of Dedalus Foundation. Reprinted in Werner Spies, Max Ernst: Life and Work: An Autobiographical Collage (London and New York: Thames & Hudson, 2006), 179.

19. Motherwell, in Spies, Life and Work, 179.

20. Susanne Kaufmann, Im Spannungsfeld von Fläche und Raum: Studien zur Wechselwirkung von Malerei und Skulptur im Werk von Max Ernst (Weimar: VDG, 2003), 118.

21. Lucy Lippard, “Max Ernst: Passed and Pressing Tensions,” Art Journal 33, no. 1 (Autumn 1973): 12-17.

22. Kaufmann, Spannungsfeld, 133.

23. Sam Gill, “The Powerful Play Goes On: Friedrich Schiller to Jacques Derrida on Play” (2009). Accessed May 5, 2023. http://sam-gill.com/PDF/schiller.wpd.pdf.

24. Huizinga, Homo Ludens, 10.

25. A three-act vaudeville entitled Niniche was shown at Wallack’s Theater and reviewed by The New York Times on October 10, 1885.

26. Dorothea Tanning, Between Lives: An Artist and Her World (New York: W.W. Norton & Co., 2001), 108.

27. Ernst, quoted in Alain Bosquet, Max Ernst: Œuvre sculpté 1931-1961, exh. cat. (Paris: Le Point cardinale, 1961), n.p.