On occasional Saturday mornings, Kasmin shares essays and interviews that expand critically on the work and practice of gallery artists. The below conversation between Liam Everett (b. 1973) and artist Maria Petschnig is featured in the gallery publication, Liam Everett: On meeting again, released on the occasion of the artist's second solo exhibition with Kasmin. On view from October 14–November 13, 2021, you can still explore the works in our online viewing room.

Maria Petschnig: Our friendship goes back maybe 15 years or so, and I remember when I first stood in front of one of your paintings in your studio, which was across from mine at the time, in the Pencil Factory in Greenpoint, Brooklyn. I was instantly moved and you weren’t even present. Both of our practices have evolved over the years. And I would say that you have been at times a very important person for me to have a dialogue about the work with, someone who has given me the much needed insight at certain points in my life. And then we shared a studio at 179 Canal Street in Chinatown in 2009/2010.

Liam Everett: Yes, and the first time I stood in front of your videos was on the Lower East Side at On Stellar Rays. I was frightened.

(M laughs)

L: I was alarmed by this sense of emotional confrontation. I still can’t articulate how I was being challenged, although the result was a wave of vulnerability that continues to alarm me and also encourages me to question what it is that I am doing in terms of my own studio practice.

M: I was thinking about how you are an artist who experiences art on a very visceral and emotional level, and that is certainly the case for me. If I don’t react to a piece of art in a strong way, then most often I don’t try and make an effort to engage with it.

L: I’m curious about what invokes the need to be moved. Because at this point, in a similar way, if I don’t have this kind of emotional experience with a work of art I simply cannot engage with it on any kind of meaningful level.

M: My impression is that you don’t look at a lot of other artists’ works, or go and frequent shows regularly. It seems that instead, you’re seeking other ways to be stimulated, through literature or being in nature.

L: That’s true, and for years that was a serious problem. I felt obligated to see as much work as I could. At times it was a pleasure. But more often it was a really suffocating experience, especially in the context of a gallery setting. Obviously, I wanted to see and consider what else is out there—to support it physically and intellectually. But I found over the years this exposure can also be a form of depletion or stagnation. I have to be very careful about what and how much I see. Especially for the past several years since I’ve been living in Northern California, surrounded by this expansive coastal landscape which is somehow always present.

M: And raising a child.

L: Absolutely, raising a child and developing relationships with everything that happens around that major life event—the school, the families, the process of parenting. Now, I actively seek this out and I’ve gone deeper, for lack of a better word. Whatever it is—forest, ocean, gardening or biodynamics—has provided a kind of rush and generated a whole new conversation in the studio, making its way into the practice as a regenerative source.

M: I relate to what you describe so well. I’ve been seeing it with myself, how I have slowly become much more selective of my resources. And at times I was wondering if I was being ignorant. But I came to realize that you become smarter about what triggers and nourishes you.

“And this is really what I’m always trying to maintain in the studio, obsessively, a place where neither the action nor idea precedes each-other, instead they rise up and appear as a simultaneous event.”

L: Maybe this idea of nourishment, which is similar to inspiration, is equally evasive. In my experience, it’s something that develops over time, and then in the same gesture you begin to eliminate those things that have been depleting you and remove them as obstacles. It’s similar to building a meditation. I know you have had this meditation practice for years now, and you also started running. Maybe the first time you ran a half-marathon you thought, “Okay, this process and training is doing something really interesting to the studio practice.” There is this power of an initial experience. But then to return to it, to do it again and again with a certain level of care, you begin to see what can be extracted from these different activities and develop a practice in and around it. When I began gardening about five or six years ago, I kept doing it, methodically and intuitively. But I had no idea what was compelling me to come home with 30 to 40 plants every time I went to the nursery, or why my attention turned to soil development, or what flowers function as super pollinators, etc. It’s only years later that I started to understand what it is about these interests that are directly feeding the studio practice, how in fact they are interlaced.

M: It is very obvious that this is what you’re thinking about a lot, the nature of practice—something one is obsessed with almost to the point of neurosis. You give yourself a task and then you try to get it done. In order to achieve that, you need to gain access to this state of free flow inside of yourself, and I’m convinced that a particular daily practice, or structure, or ritual allows you to slow down and relax, to tune into a deeper level, while forgetting what’s around you. But while they happen, you’re somewhere else mentally. Only afterwards do you step back and look and start to make sense of it. So it’s not just going to your studio and starting to work. It’s a process.

L: What you are saying here makes me think of this translation of yoga: to yoke, is that right?

M: I haven’t heard that term. What is it?

L: I read that somewhere years ago. I don’t have a yoga practice per se, but I relate to this notion of opening the body through stretching and repetition and breath, a constant back and forth, yoking between two extended points. For me, that’s another good metaphor. It’s not just going to the studio in and out the door, it’s all these other things in and around the studio, the daily preparation, even if it involves just moving a chair from one corner of the room to another. It can be as simple as getting a good night’s rest, eating with care or sweeping the floor. It’s a kind of massive filtering system, a subtle and complicated set of actions that are all thoughtfully laid out to create openings and to avoid stagnation. I know when I’ve entered the studio and I haven’t gone through this, I can feel blocked right away. If this occurs then I have another kind of system that kicks in, a way of shifting, a series of exercises that essentially create movement and fluidity, whether it’s in my body or my thinking or seeing.

M: You gain access to it in other ways and it works? You know what to do?

L: At this point yes, because I have had the luxury of being able to maintain the practice. You know it’s different when you have a day job. But even when I had my day jobs, I tried, to a state of exhaustion, to figure out ways to prepare myself for the studio, so when I arrived, I was as effective as I could be, making decisions with clarity and intention.

M: Would you say that you always work at the same pace? Can you sometimes be extra efficient and fast, and if so, will it yield the same level of quality?

L: I’m always working as if I have a deadline. And for years, when I didn’t have a deadline, I would just pretend to have one. It’s probably a little bit neurotic to function this way, but for the past 10 to 15 years, I have been in a rhythm where I feel when I’m in the studio or heading to the studio physically or metaphysically, it’s almost always accompanied with a sense of urgency.

M: But, what about after a show? You must be empty and depleted.

L: Sometimes this is the case, a mix of depletion or emptiness. But this is often short lived, as the fear of stagnation chases me back into production.

M: Is this a fear? Because I don’t regard it as a fear, it’s interesting that you say that.

L: This commitment to practice has become a lifeline. I’ve become reliant on it as a form of navigation, as a way to make sense and of course nonsense.

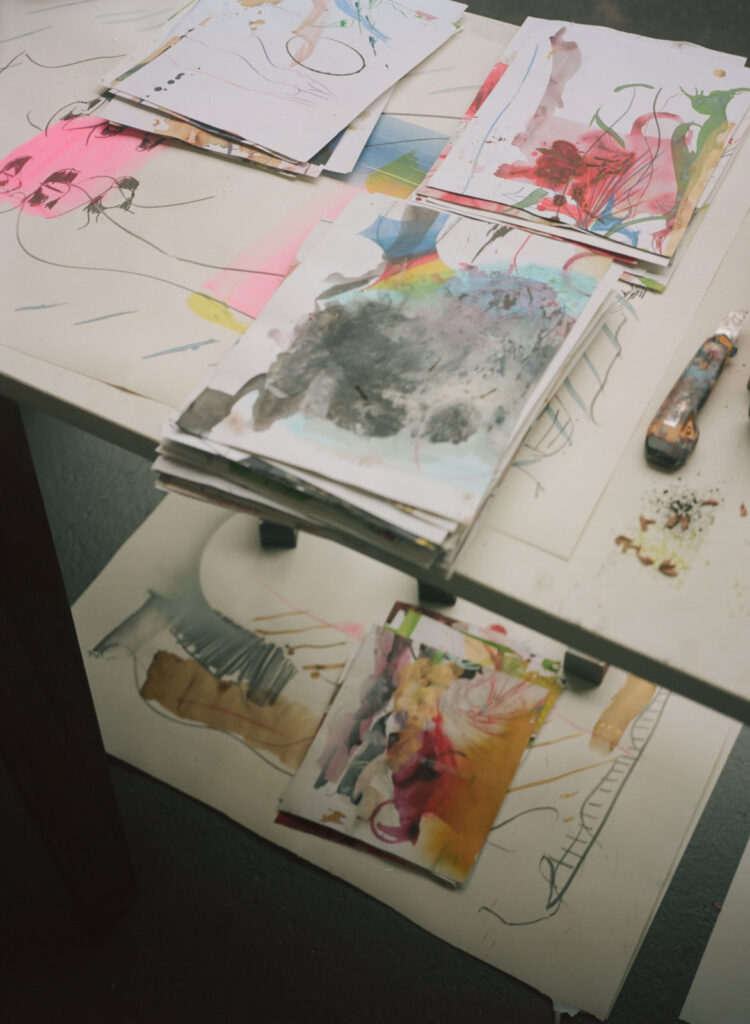

M: It gives you a kind of strength. Somehow this makes me think of the photographs that Emilia Turner took of your studio earlier this year.

L: The photo shoot was originally organized for the site-specific mural I did in San Francisco in the spring. Yet the result of these images and the information they extracted from the studio opened up an entirely new lens on the work. Quite literally they revealed that which is usually concealed, i.e., practice itself. In each of the images you can see this phenomena unfold, floating in the form of light, animated and independent. There is definitely a kind of power when something so incredibly evasive is allowed to appear.

M: I was reflecting on how I evolved over the years, how I slowly departed from painting, from constructing physical objects, more or less, to making videos and becoming more of a story teller during the last 10/15 years or so. I’m still surprised on a regular basis by what creeps to the surface in terms of influences, information or underlying themes. It could be a book that I had read months earlier, a mood connected to a person in my life, or some strong memory from ages ago. Aren’t these sorts of surprises little magic gifts that come our way as artists? They prove that we are able to tap into deep pockets of stored information and lived experiences within. Do you find that?

L: Yes. And every time that happens, I’m thrilled and I applaud it, craving the more absurd moments of these surprises. For me the analogy is, you’re investigating a very specific kind of subject and then suddenly you fall upon something from a completely different realm and you say, What the hell is this doing here? It’s the idea of looking for something and perhaps feeling a little bit safe about where your frame of mind is, and then wham! something shows up in the work and it might even be threatening. Ideally these moments appear foreign and otherly or in such a way that they confront you, or even indict you. Do you have this experience?

M: Now where the periods of incubation, research and collecting material last longer, this happens somewhat more consciously than creating out of a state of urge. More time passes. The results take different shapes, they come through differently. It’s not quite like you describe it. I would have to think about it.

L: Well, you have these incredibly researched subjects: this last film that you’re about to premiere, you spent—what? Two years?

M: A year and a half.

L: And then I’m also thinking about the Russian photographer. What was his name?

M: Viktor.

“I think that’s the most important thing to know that the work potentially has its own half-life and will thus continue to appear and reveal itself.”

L: Who you found through his amateur photographs in the flea market. So you have this initial interest, this starting point of entry, even though there are probably things that preempted that. Now, fast forward to the end of that project, after your trip to Saint Petersburg and back to New York, and so forth. In hindsight, can you say that you were surprised with the outcome of these projects?

M: Completely. In my work there’s a lot of—and I’m more receptive to it now—chance or unexpected obstacles involved. Or a crisis, big and small, may force a big decision out of me. And you make it part of your practice. Maybe for a moment you are taken aback, you are annoyed that now you need to come up with something else, but then you realize it is actually a blessing in disguise, a plan B forcing you to shift things, which suddenly leads to a whole new outcome, one that is multi-layered and more indirect.

L: And how do you figure that out?

M: Intuitively.

L: I was going to get there. You said the word, so it’s an intuitive process of sensing.

M: That’s where the meditation comes in handy.

L: Tell me about that, how does meditation come in handy?

M: I do it every morning, and often ideas enter—or afterwards I’m prompted to try this very thing out that day. Or, it happens that during a sitting I realize how to improve something, certain aspects about a project suddenly become clearer. But it’s not that I meditate wanting to consciously use the session to find that out; these things may pop up randomly.

L: So that’s interesting and foreign to me.

M: I could imagine you being in the garden and it leading to a similar outcome in the form of a sudden thought—of a knot untying in your work, so to speak.

L: Yes, I can relate. And it’s a good segue to the question I’m often contemplating. You have this idea that rises up during meditation, and I imagine you might also have this when you’re running.

M: Right, it does happen.

L: With both of those practices there is this kind of repetition inherently involved. It’s not something you do once. Many of us do, but then it doesn’t develop. You have this repetition of gestures and actions that inevitably birth ideas and/or concepts. So here is my question to you: if you follow that initial idea, how loyal do you remain to it? You have a clear idea. You see this person. You envision the scenario, it is compelling. Are you driven to hold onto that original concept, to really see it through until it makes itself manifest in film or installation? Or is it something you use as a guide, leading you on the way, following it as it morphs and flows into other things?

M: More like the latter. Everything is constantly moving and changing and taking another shape.

L: Sounds like you’re still painting, Maria.

M: Well, you are just constantly thinking about things, and you are venturing out and then going back. Embarking on a film, you are taking a new, unknown path; you look around, and simultaneously you are aware of your own set of rules. Sometimes it is scary—and come to think of it, that could actually manifest itself in and explain some nightmares of mine. It’s that I need this freedom and I need to be able to have many choices, and it’s a trial and error situation. I can’t, and I don’t want to, figure it all out in the beginning, but it is definitely scary at times. I’m terrified that I will lose myself or I will get off my way, but eventually I know how to return and I find the entry way again. It’s a different kind of practice than what I was used to when I was still painting, that’s for sure.

L: And early on?

M: As a painter, I used to have a very structured, similar daily routine: I would go to the studio, continue tasks that were left from the previous day, etc. It is still a very intuitive practice to this day, but I’ve developed a much looser system, not in terms of being dedicated to what I do, but in regards to setting up just one or a limited number of tasks. Because now I research more, and I write and prepare before I know what this is going to be and what it entails, how big and on what level I like to do this. The upside—and at the same time, the downside—of it is that this doesn’t result in daily progress. Rather it could be that a certain conversation leads me to the solution, or I somehow realize that I now can only read and nothing else would make sense. So I allow myself to react to a more ebb and flow-kind of practice and output. The decision-making progress is more varied. But with me—and this is why I was surprised by your answer about you never feeling completely empty and depleted—I sense these aspects in my work extremely strongly. Before making a film, I’m filling myself up with information, material and ideas until I’m boiling over, and then all I want to do is get to work. Until I’m getting what I’m after and it becomes clear that the project is coming to a completion. Afterwards there is a great void, and I have no idea what I will be doing next.

L: I understand. I’m really envious.

M: Well, and I can see how the structure of working you have in place is strong and beneficial.

L: Yes, the structure is critical. But I’ll just say, only for the sake of our exchange, that the primary difference in our practice is that—and this also answers the question of how I can be “ productive”—I am no longer really working with ideas. In fact, I am avoiding them, or even destroying them, when possible. For a long time though I was rigorously doing the opposite; I was scavenging for ideas in the pure sense. And then there was a certain point where I intentionally decided to stop looking for ideas so much, and if and when they did arrive, I would attempt to obliterate them or simply move in the opposite direction. So, if and when I see an image or a form, I simply invert that form or gesture. This is why I keep a running list of self-imposed restrictions that are set up in the studio, specifically to destabilize the original idea.

M: Obstructing.

L: Yes, you can call it obstruction. But also for me, the point is to not be dependent on the idea, neither as way of beginning nor ending. In my experience this reliance can be debilitating and lethargic. How to be completely free of it, of course, opens up a whole other series of questions and problems.

M: Right. Why do it the simple way if it can be complicated instead.

L: (laughing) Inevitably, I do have ideas as I’m working, but what I attempt to do is hold a space in which they can only arrive within the same gesture as a physical action. And this is really what I’m always trying to maintain in the studio, obsessively, a place where neither the action nor idea precedes each-other, instead they rise up and appear as a simultaneous event.

M: I know exactly what you mean. And I would say it’s exactly these aspects that most young art students and new art practitioners must figure out themselves and slowly come to terms with, get through and beyond. You can laugh, you can call it a silly question, but here it goes: what would the 10-year-old Liam say if he could see you now producing this work and having this life set up around it?

L: I want to laugh and say it’s a silly question, but I think it’s also a really beautiful and challenging question.

M: Because you seem to ponder and reflect upon what it is that you do every day. So you step outside yourself and you try to look at yourself, at how people view you from the outside. This goes a little bit in that direction, but from the eyes of a child.

L: It’s very interesting you say 10-year-old, as my daughter is now 11. She is wonderfully inquisitive and critical, considering all aspects of life now. So maybe I have asked myself that same question before. I would like to think that my 10-year-old self would approve of what his elder has become. Especially because even at 10, I started to feel the constraints—or rather, realization—that I wasn’t fitting into the mold that was imposed around me, and I was struggling. It was the beginning of the great struggle (laughing). But very soon after, when I was 11 or 12, I got my first part as the boy in Beckett’s Godot.

M: Wow, that’s interesting. Tell me about it.

L: It was really my introduction to the theater as a 12-year-old. I had the luxury of being around these odd adults who were professionals, and so very demanding of themselves as artists. And of course, beautifully eccentric and neurotic. As a kid I found this new world or realm of the theater to be wildly fascinating. After doing that for about a year, I didn’t want to go back to school. It was the beginning of alienation because it just felt like school was incredibly limited and oppressive. What appealed to me instead was the intensity and demanding nature of being both on and behind the stage, especially in regards to rehearsal. I was completely in awe of how the actors were rehearsing all the time, in the dressing room or during travel, always repeating their lines as they went about a daily routine. It was a gesture that was somehow woven into their beings. And even at the age of 11 or 12, I wanted to have access to that intensity, that commitment, despite that fact that I had no idea what it was or even what to name it. I’m not sure this is clear even now, and definitely not to my 10-year-old self.

M: I’d say that’s a very good answer. It makes me wonder what is the greatest compliment you’ve ever received?

L: For that, I would say it’s those moments when someone who’s been living with the work reaches out and expresses at some level that they’ve developed a relationship with the painting over a number of years. Ironically this happened last week—somebody reached out and said, “You know, the strangest, most exciting thing is that every time we sit with your painting, it looks completely different. It raises a different conversation or a different regard.” I think that’s the most important thing to know that the work potentially has its own half-life and will thus continue to appear and reveal itself.

M: That’s beautiful. When I hear that, I wish I were still a painter.

This conversation between Maria Petschnig and Liam Everett took place in June 2021.

Maria Petschnig is a Brooklyn-based filmmaker and video artist. By dealing with fantasy, voyeurism, privacy and memory, Maria Petschnig captivates and manipulates the viewer with seemingly familiar images.

Petschnig’s work has been screened and exhibited extensively both nationally and internationally. She is a recipient of the Foundation for Contemporary Arts NYC grant, the Rema Hort Mann Foundation Grant, New York; as well as a National Grant (video & media art) by the Austrian Federal Ministry for the Arts and Culture, amongst others.

In 2015, Black Dog Publishing, London printed a monograph on Petschnig’s videos titled NINETEEN VIDEOS (2002 – 2015). “Uncomfortably Comfortable” (2021) is her first documentary feature, distributed by Sixpackfilm. It will premiere at Duisburger Filmwoche, Germany in November.