On occasional Saturday mornings, Kasmin shares essays and interviews from the gallery archives. The below essay on Bosco Sodi (b. 1970) by Juan Manuel Bonet appeared in the artist's comprehensive monograph, published by Rizzoli Electa. Sodi's second solo exhibition at Kasmin, Vers l'Espagne, went on view at 509 West 27th Street in Winter 2020. Learn more in the accompanying online viewing room

I often recall the days at the beginning of the now long ago year of 1980 when Robert Motherwell visited Madrid. Motherwell was without doubt the most Francophile of the New York School of painters, a painter always in dialogue with poetry who, from 1967 on, achieved a high degree of essentialism in his Open series, among which I, personally, feel a special predilection for the blues. On several occasions he said that if, in his eyes, the most important name in his discipline during the first half of the twentieth century had been Matisse, the second would have been Joan Miró, the most surrealist of the Surrealist painters, whose work he had the opportunity to know first hand in his youth, thanks to his solo exhibitions at the Pierre Matisse Gallery (founded by Henri Matisse’s son, the New York art dealer who had represented the Catalan since the mid-thirties), and, above all, thanks to his 1940 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

After an initiation period in Paris that somehow paralyzed him, Bosco Sodi, a Mexican painter born in 1970, spent part of his youth in Barcelona, the city where Miró was born. Sodi lives in New York now, and his work is demonstrative of a truly colossal, international activity. Always under the sign of art and culture, and without relinquishing any of his roots, he embarked last year on the adventure of painting a series of ten white paintings directly inspired by a Miró work in concrete. With the title, Vers l’Espagne (Toward Spain), which seems to refer to his own journey as an apprentice painter in those years when he made the Paris-Barcelona journey (which was contrary to the Barcelona-Paris journey made by Picasso and by Miró himself.)

The work in concrete chosen by Bosco Sodi as a point of departure for the series Vers l’Espagne is actually three: three acrylics on canvas, each 105 ½” (268 cm) high and 139” (353 cm) wide, painted by Miró in his studio in Palma de Mallorca, between May 20 and May 22, 1968, and all three with the same title in French: Peinture sur fond blanc pour la cellule d’un solitaire (White Background for the Cell of a Recluse). Three silent, white paintings, all three featuring just a simple trembling line. Three almost minimalist paintings, although obviously of a sensitive, unsystematic minimalism. Three paintings that were seen first that year in a retrospective at the Maeght Foundation in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, and in the one that later took place in Barcelona at the Antic Hospital de la Santa Creu. At the Miró Foundation they are arranged one painting per wall in a kind of small chapel reminiscent of Mark Rothko (I think of Houston, Texas, and I also think of the enveloping music of Morton Feldman for Houston), a space designed for that purpose by Josep Lluís Sert, the architect of the building, who also designed the aforementioned studio of his great friend and accomplice in Palma de Mallorca. On the corresponding cartouche, the foundation appropriately reproduces a well-known passage from Miró himself: “Conquering freedom is conquering simplicity. At the limit, then, one line, one color, can make the painting.” Miró said those words precisely that same year, 1968, into the microphone of the journalist Pierre Bourcier, who was interviewing him for Les Nouvelles Littéraires.

The first phase of the Vers l’Espagne project consisted of Bosco Sodi’s trip to Barcelona to see the Miró chapel again for himself. He had the authorization of those responsible at the foundation to remain alone in the room for two hours; some photographs show him in the room, going up to the paintings, becoming imbued with and pervaded by the spirit of their author, meditating on Mironian freedom.

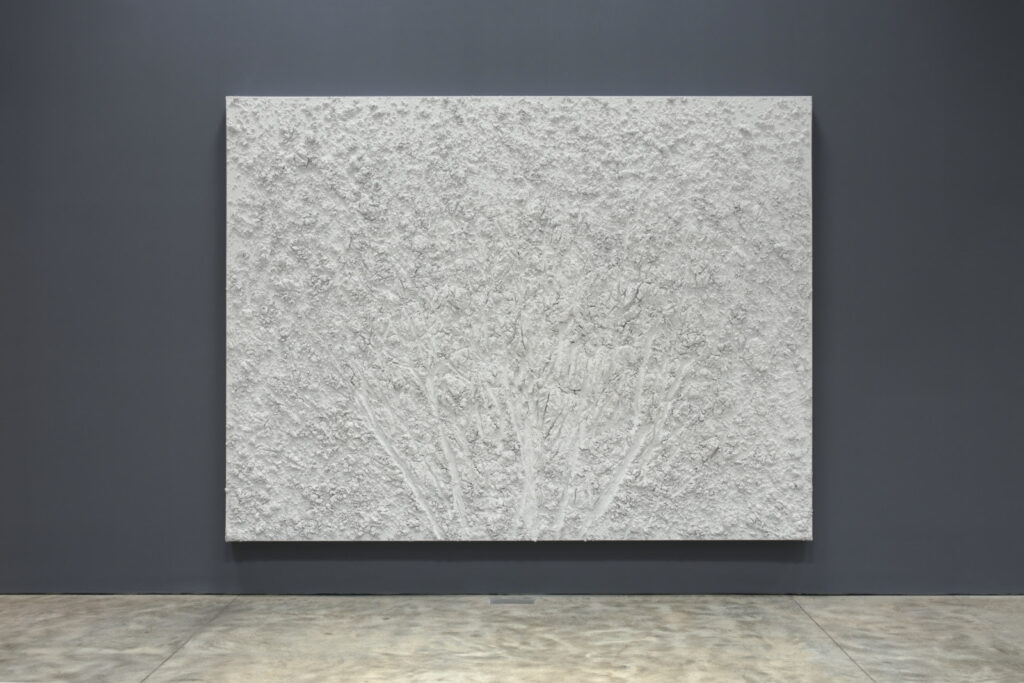

Paintings that consequently are also landscapes, in a way, abstract landscapes, visions of nature, allegories of the tree swaying in the wind, of the vigorous branches and of the delicate lace of the leaves, swaying now in the flow of the paint, white like the snow.

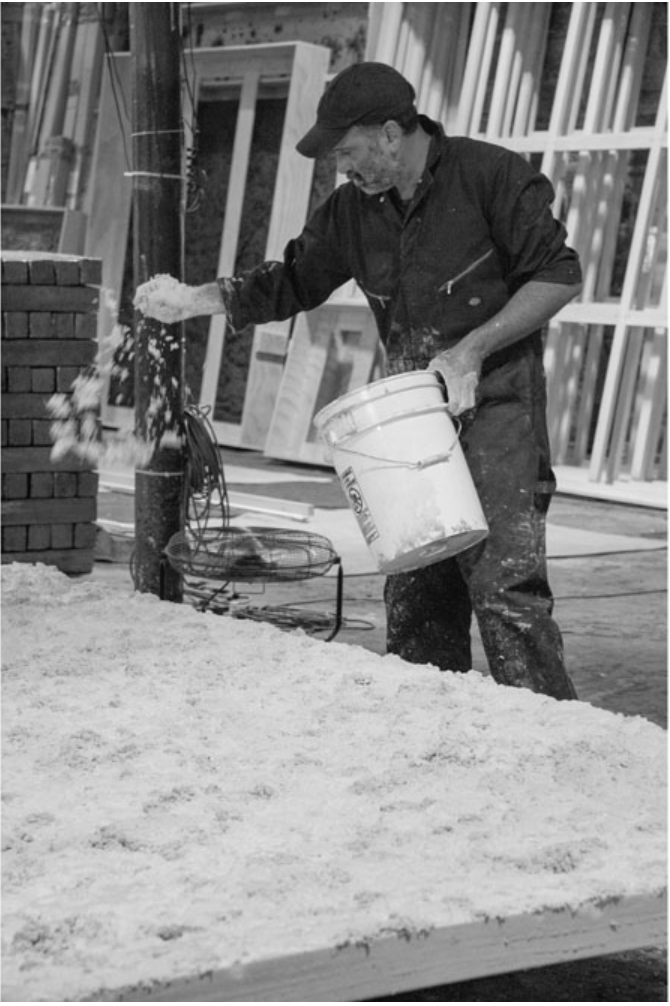

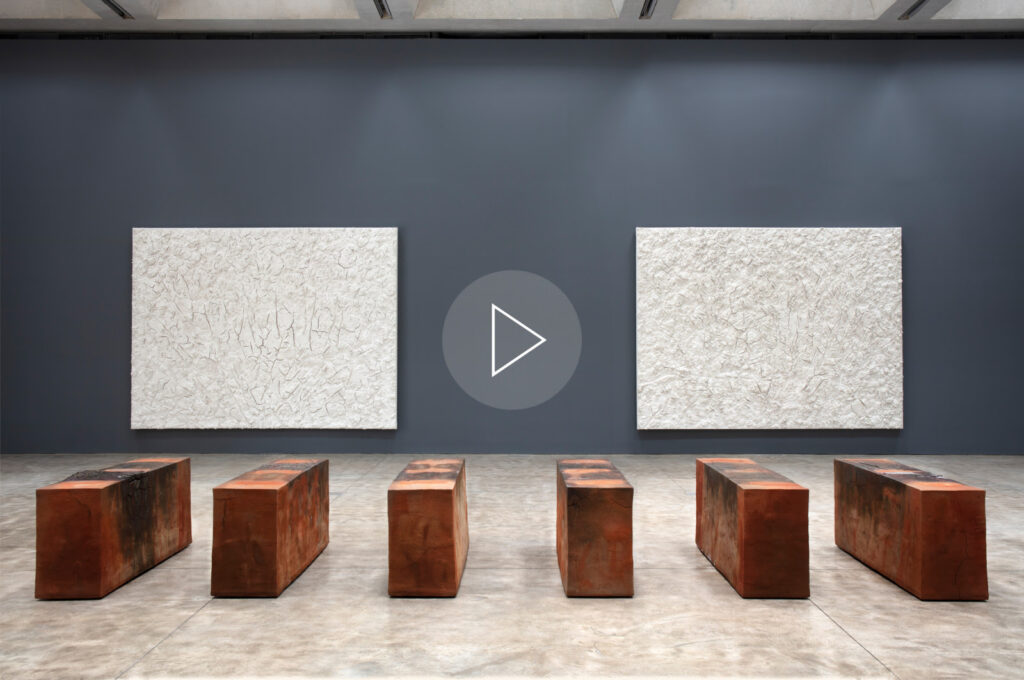

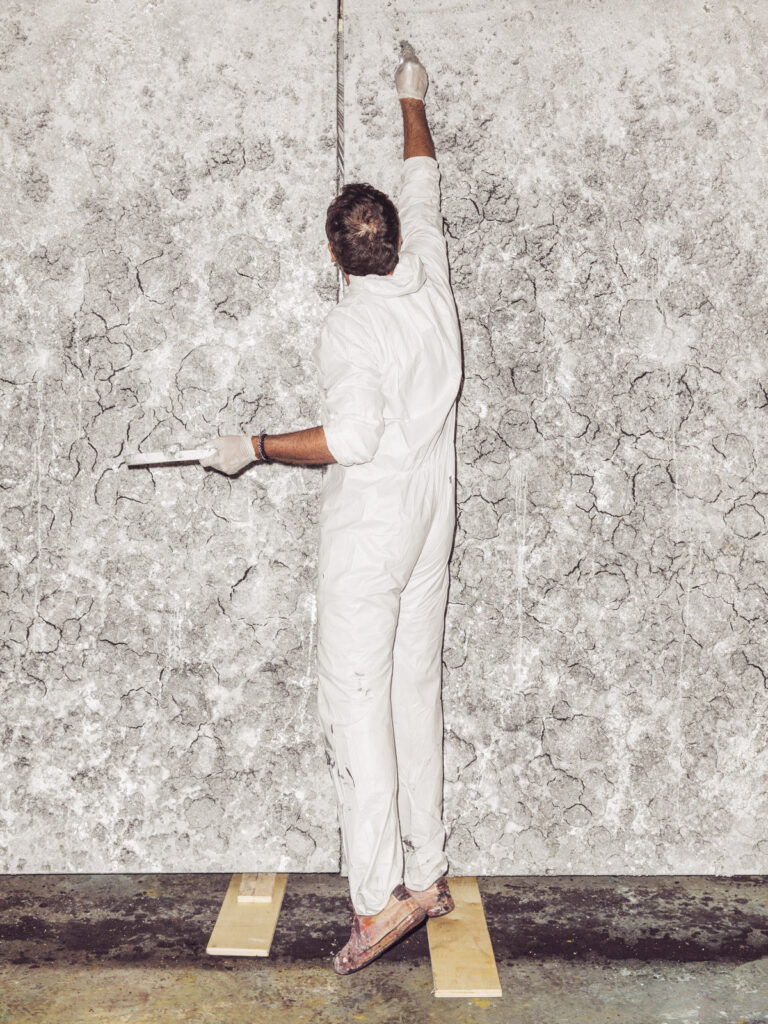

Back in New York in his Brooklyn studio, Sodi began to work industriously on ten white paintings, all with the exact same format as those of Miró, which had been the pretext for the project. Paintings, in all other aspects, without any specific reference to that pretext. Nothing like d’après Miró, no pastiche, much less any irony or pop vulgarization. No simple line as their distinctive feature. The Mexican’s paintings were the result of an action, that of collecting dry tree branches in the snow, and then scrubbing them onto the surface of the painting; there is a video in which he is seen training for that action, let’s call it a dance, which would have his studio as its stage. Paintings that consequently are also landscapes, in a way, abstract landscapes, visions of nature, allegories of the tree swaying in the wind, of the vigorous branches and of the delicate lace of the leaves, swaying now in the flow of the paint, white like the snow. Materic paintings, involving the coexistence of a plan and chance, and even accidents (that trace of a tree and then the ones with cracked crazing that are “trademarks” that sometimes look like those of an arid, dry, thirsty land); control and disorder; matter and lightness; minimalism and automatism in the style of Jackson Pollock. In this last respect, there is the importance of Surrealist painting in general for the generation of the inventor of “dripping,” which is also the generation of Motherwell (it was the time of the Artists in Exile, 1942, precisely in the Pierre Matisse Gallery: André Breton and other Surrealists had chosen the North American option), as well as that of Miró in a very special way.

In various interviews, Sodi has spoken about his way of conceiving a painting. From his eminently intuitive work, without thinking, with only a very elemental plan, a pretext, a format, a color . . . He always emphasizes that color, the idea of a color, is usually first for him. In this series he has chosen white. He remembered childhood experiments in recreational science on more than one occasion with his father, a chemical engineer. He doesn’t hesitate in extolling a certain infantilism, a certain relapse into childhood, enjoying oneself like a child. Apart from that, Miró, who was so often accused of painting like a child, did not dislike the typical mockery: “my child made that.” Among his great works of the thirties are his panels of 1933, extremely energetic and invigorating, for the nursery of the children of art dealer Pierre Loeb, and in 1938, another work of similar inspiration and grandeur for the children of Pierre Matisse: recidivism in painting intended to be enjoyed by children. And on the subject of trees, Miró in one of his most reproduced statements of 1958, made to the French critic Yvon Tallandier, said that beautiful thing that goes “I work like a gardener,” which in French was translated as Je travaille comme un jardinier (Paris, XXème Siècle, 1963); and in Spanish, as Yo trabajo como un hortelano, “I work like a truck farmer.” (Barcelona, Gustavo Gili, 1964). That Spanish translation seems very pertinent to me, since the word farmer is more rural than the French gardener. More Mironian, in short.

In the end, after painting the ten, beautiful, white paintings, Sodi painted another two in anthracite black. Many artists have been tempted by the monochrome, and it is certain that he is one of them. These artists have especially cultivated the two colors that do not seem to be colors: black and white.

Sodi’s visit to Barcelona this year to immerse himself in Miró’s three paintings was actually a return home. When we met at the beginning of the century he was living in Barcelona, where, in 2001, he had his first solo exhibition, and where he kept an open studio. There he found gallery owners, collectors, and critics who were so attentive to his work that when, in 2008, he decided to go to Berlin, there was no lack of press coverage describing it as a flight. The flight was relative: in 2011, he would have an untitled solo show with Carles Taché who, for a time, was the art dealer of both Antoni Tàpies and Sean Scully, and the following year, he would return to the same gallery with another exhibition titled Sahara, which was made up of white monochromes notable for their extreme essentialism, which somehow prefigured the spirit of the paintings inspired by Miró. Barcelona has always welcomed creators from the New World; at the beginning of the past century, the Uruguayans Rafael Barradas and Joaquín Torres-García lived there as well as the Mexican David Alfaro Siqueiros. In the literary world of the sixties, two Nobel winners chose it as their residence: the Colombian Gabriel García Márquez and the Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa. When Sodi arrived, the two most powerful presences in the Barcelona art scene were evidently Miró and Tàpies. Miró had already passed away, but he was still on everyone’s mind, thanks, among other things, to his beautiful foundation, where we were able to see so many great shows of his work as well as the work of other artists, among which I remember one that, in 2000, was dedicated to Rothko, another of Sodi’s guiding lights. As for Tàpies, our painter visited him once in his studio in the Grácia neighborhood. The studio (one of the great works of the architect Josep Antoni Coderch), the artist, and his discourse had a great impact on the young man. He remembers concretely that the older man, while looking at photos of Sodi’s works, advised him to read Eugen Herrigel’s book on Zen archery, first published in Surrealists in Mexico City). A separate and unclassifiable geometer, Mathias Goeritz, arrived somewhat later. It is necessary to mention also Neo-figurative painters such as Cuevas himself and Francisco Toledo, whom Sodi greatly admired, among other reasons, as being a promotor of cultural and social projects in the city of Oaxaca. Later on, an abstract generation would emerge for whom Tàpies would be a guiding light, and the case of Vicente Rojo stands out: he was born in Barcelona, but became a part of the Mexican scene a few years after the end of the Spanish Civil War, but he always maintained strong ties with Spain, in general, and his hometown in particular.

Revisiting Mathias Goeritz’s gold monochromes, his “emotional architecture,” and his collaboration with Luis Barragán, this most solitary and important architect of modern Mexico, has been studied (by Arden Decker, in the catalog of AG, the 2015 solo exhibition of the painter at the Hilario Galguera gallery, Mexico City) as the precursor of some of the aspects of the work of Sodi. I fully agree and not only about the golds on which I will comment immediately. If we analyze any relevant painting by the Mexicanized German, for example, his gold metallic relief Mensaje (1967), we understand that there is a common sense of monochrome, a common orography, a common non-compositional desire. A non-compositional desire that was also, decades earlier, that of the Polish Unist Władysław Strzemiński, who greatly advanced the monochrome and whose work also interests Sodi.

As has Goeritz, and, more recently, Sean Scully, another very painterly painter with a studio in Barcelona (and, incidentally, very vitally and aesthetically linked to Mexico: the last of his exhibitions that I had the opportunity to see focused precisely on that link; I found it a few months ago in Guadalajara, Mexico, at the Hospicio Cabañas), in recent years, Sodi has felt the need to express his creative exploration in the three-dimensional field. I am interested in his installations with gold volcanic rocks, fired in a ceramic kiln, that can be approached as Zen rock gardens, although others rise up like murals (see, for example the 2016 Lienzo I [Canvas I,] in which the lienzo only exists in its title), but I find them still more fascinating because of their simplicity, because of the economy of the means that sustains them; I am also interested in Muros of fired clay bricks (see, for example, the one that, with symbolic and political intention, was set up in Washington Square Park in New York in 2017), and, in general, his work with terra cotta, in which he admirably reconciles minimalism: Donald Judd and Sol LeWitt on one side (with those who, in 2018, came together in the very interesting collective A Tradition of Revolution at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas), and archaism and ancestral craftsmanship on the other, which takes us directly to that Indo-American world, which, from Joaquín Torres-García onward, has seduced so many New World artists. In more concrete terms, we are thinking of Álvaro Siza’s Clay Pavilion at Casa Wabi, and of the admirable work that is done there with children and adults of indigenous communities, so that traditions in the domain of clay are not lost. With his bricks and his cubes, made in his studio there, then dried in the sun and fired in a traditional kiln using coconuts, among other combustible materials, and with the walls and columns he makes with them, he reaffirms the importance for their creator of the dialogue with nature and with the landscape. We go almost without transition from the minimal, a minimal lived poetically, unsystematically, to Arte Povera and to Land Art, and there is nothing strange in the sense that among his reference artists, Sodi always mentions Richard Serra, Walter De Maria, or Jannis Kounellis, for whom he organized an exhibition at Casa Wabi in 2017. If the very title of the Caryatides, some of which were seen so titled in that same year in his solo exhibition at Kasmin, leads us to the homeland of the third of those Povera artists, it is important to mention Bosco Sodi’s three-dimensional work in fired clay: the army of sixty-four monumental, impressive Atlantes located outside the foundation.

He is a perpetual nomad, wherever he goes, whether it be Japan, China, India, Morocco, Croatia, or his own home country (“Mexico is color,” he told Barcelona critic Jaume Vidal Oliveras almost at the beginning of his career, adding that in Mexico “color is everywhere.”)

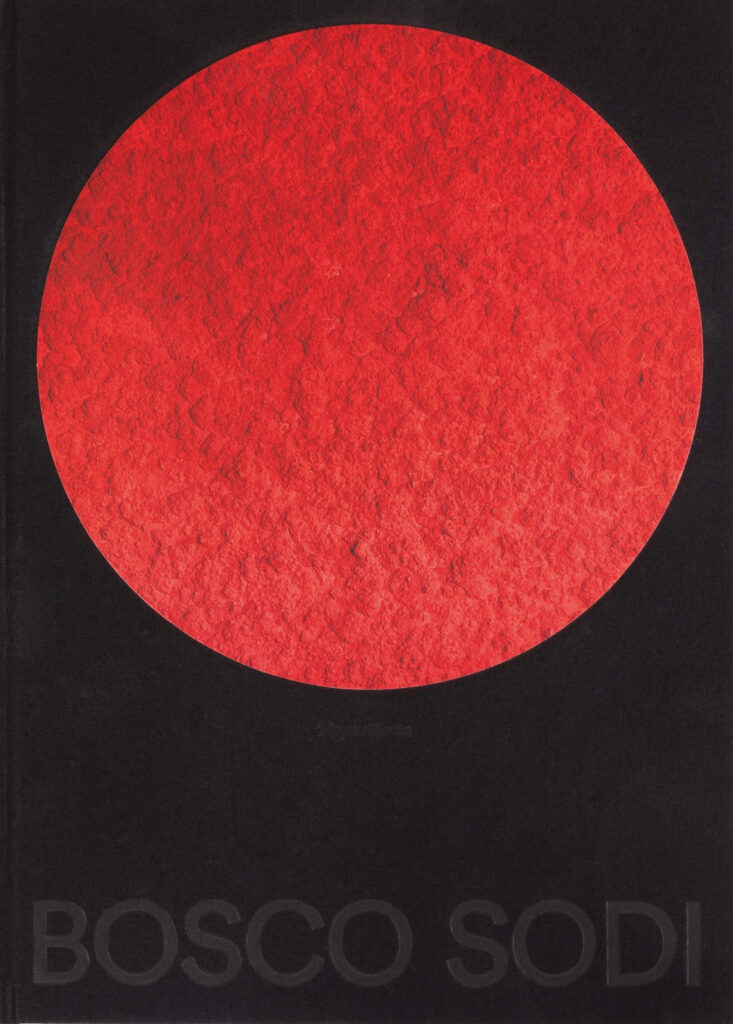

The white of Kazimir Malevich and of the caryatids, the black of Richard Serra and of Kounellis (and of Motherwell: his Elegies to the Spanish Republic) and of the stones of the Ryōan-ji, the gray of cement, the gold of Goeritz . . . The palette of the born colorist is not limited to those colors, and, according to Lilly Wei, Sodi is just that. He is a perpetual nomad, wherever he goes, whether it be Japan, China, India, Morocco, Croatia, or his own home country (“Mexico is color,” he told Barcelona critic Jaume Vidal Oliveras almost at the beginning of his career, adding that in Mexico “color is everywhere.”) He finds time to spend in places, sometimes very remote places, where he can acquire natural pigments, and, in this way, he surrenders to the warmth of the reds, the ones with which he made himself known to us (and that Ando liked so much: see his meaningful text about this) and to those who have always remained faithful (remember his red expansions of 2017, the first of which appeared in the previously mentioned solo exhibition at Kasmin, and the show he had with the title Voragine at the Galeria Luciana Brito in São Paulo), to the luminous oranges of Bonnard or the most Bonnardian Rothko, a few pinks that seem to come directly from the architecture of the very Mexican Luis Barragán (our painter, incidentally, has work in his foundation, established in the Swiss town of Birsfelden), to the earthy ochers of the bricks, to the jungle greens, Amazonian, and, of course, also to the blue, the blue of the sky and the deep-sea blue, the “color of dreams” of the most splendid Miró, the color of some of the works in Motherwell’s Open series, the Saturated Blue of Sam Francis (another painter fascinated by Motherwell and Japan, and whose work particularly pleases Sodi), and, without forgetting the Organic Blue of Yves Klein (Sodi’s title): another reader (I have already mentioned him) of Herringel, another Japanophile, for whom his stay in Spain was important (in the mid-fifties in his case).

Since I just mentioned that meteorite that was “Yves the monochrome,” and I am not the first to do it on purpose, I must say that in some of his most enthusiastic works, Sodi seems to fall directly in the wake of the reliefs éponges (sponge reliefs) of the nouveau réaliste for the opera house in the German city of Gelsenkirchen. Paintings by the Mexican artist such as the aforementioned Organic Blue (2009), painted in Berlin, and which was seen the following year in the Museo Jumex of Mexico City, or the red Pangaea (2010), painted in New York, and presented that same year at the Bronx Museum, impress us with their enormous dimensions (in both cases 157 ½” by 472 ½” wide), and by their imposing presence, we could almost say heroic. Exempt paintings, no doubt, but they occupy the wall with the ambition of murals but, of course, of a type very different from those of the Mexican masters of the time of the Revolution. Paintings he created as if in a state of trance (I recommend that the reader watch the respective videos about the creative process associated with both works, that of the Catalan photographer Miguel Soler-Roig in the first case, and of Sebastián Hofmann in the second), and we certainly detect a performative side in his way of working the pigment without brushes, with his hands, in dripping plan, in battle of the canvas plan.

Sodi is a free painter like Miró, and intrigued by materials like Tàpies, like the Jean Dubuffet of Matériologies, like Anselm Kiefer, or like Miquel Barceló, the last three of whom he has also quoted on more than one occasion, although primarily the first two. He is a friend of always remembering the green paradise of childhood, and his own in particular, in an environment where chemistry and culture were mixed. He is voluntarily Elemental, as he titled his 2017 solo exhibition in a magical place, the Museo Diego Rivera Anahuacalli in Mexico City, a solo exhibition curated by Dakin Hart, senior curator of the aforementioned Noguchi Museum, and in which his pieces dialogued, both inside and outside, with the volcanic stone on which the building is constructed, the work of the singular painter and architect Juan O’Gorman (pp. 208–209). He is, in short, a creator who, like Miró and Tàpies and his other guiding lights, passionately lives in painting, his primary guide, and who assumes from that freedom and from his passion for the material, the plural memory of his trade, and of his own wandering, begun in his native New World, continued in the Old, and which today also encompasses the Far East. In the white series Vers l’Espagne, recently exhibited in the city where he resides, he gives us the fruit of his assimilation, both intuitive and intelligent, of the teachings of the most free, most Japanese, and most essential Miró.