On occasional Saturday mornings, Kasmin shares essays and interviews that expand critically on the work and practice of the gallery artists. The following conversation between Ali Banisadr and The New York Times best selling fiction writer Ottessa Moshfegh was originally published on Grand Journal.

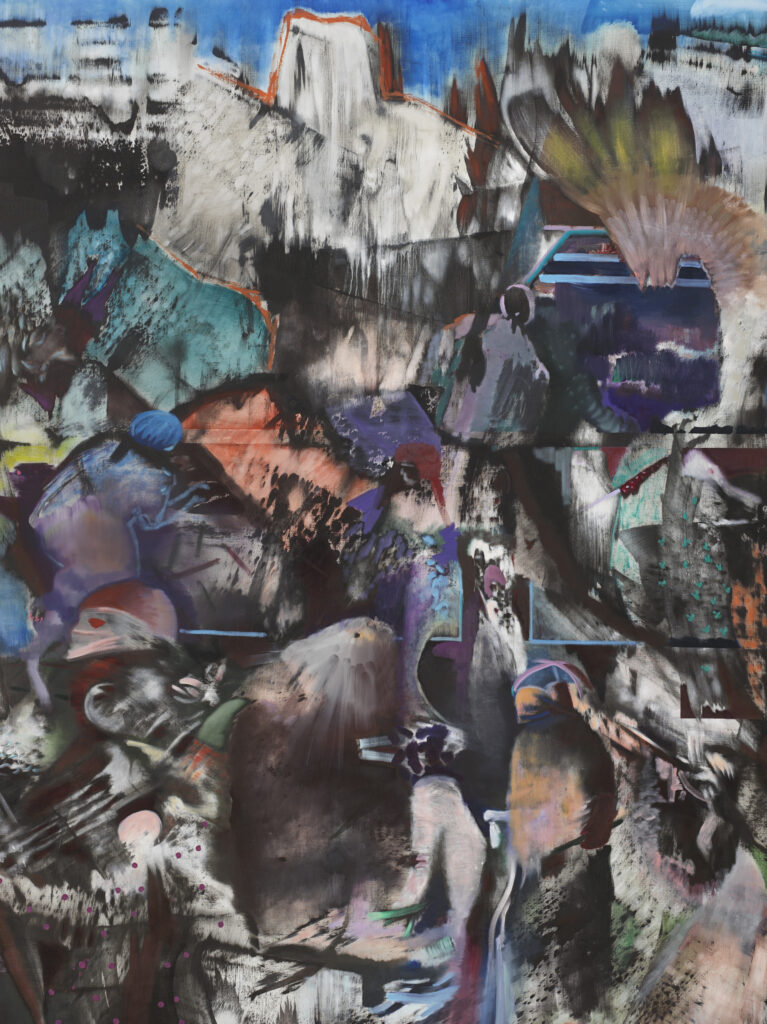

“If I had to pray to anyone, I’d choose Whoopi Goldberg’s character from Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” wrote Ottessa Moshfegh in a “letter” to Donald Trump in 2018. “She makes me laugh. She has a sense of humor.” It’s a good thing that Moshfegh, too, has a sense of humor. Her wit elevates the otherwise bleak landscapes of her novels, in which repulsion—of people, of the body, of life—is a connecting thread. In her brilliant 2018 novel, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, the protagonist seeks to escape those feelings in a miasma of prescription meds that cause her to sleep in her New York apartment for a year. In last year’s Lapvona, set in medieval Europe in the aftermath of a plague, we get to see what Hieronymus Bosch might have written had he been a novelist. Hint: there is cannibalism. Complex tides of revulsion and compassion also ripple through the work of artist Ali Banisadr. His large, tumultuous canvases teem with life, but are stippled with terror and conflict, an echo of his childhood in Iran during the Islamic revolution and subsequent war with Iraq. No wonder Bosch, Dante, and Goya are the three historical figures he’d like to meet for dinner. Well then, pull up a fifth chair: Moshfegh is bringing the appetizer.

– Aaron Hicklin

GRAND: Ottessa, I’m very happy you are zooming for this conversation from your bedroom. The unnamed narrator of My Year of Rest and Relaxation spends a year in bed. Your room looks like the room of someone who doesn’t want any distractions when they’re sitting in bed writing.

OTTESSA MOSHFEGH: That’s interesting you say that because to me it is so distracting. You’re also not seeing what’s on this side of the room.

GRAND: You’ve got those two icons on either side of the bed.

OM: These are my Chinese couple.

GRAND: And there’s a head on your bedside.

OM: That’s for my hats.

GRAND: How many hats do you have?

OM: A lot. I’m a bit of a collector of things.

ALI BANISADR: I have so many hats, too. In school they used to call me the guy with the hat.

GRAND: Perhaps you can start by telling me how your day is going so far?

OM: I haven’t worked creatively today. I’m always surprised by how much time I need to do the really tedious tasks like emails and making lists and booking things and feeding the dogs— that is still kind of the bullshit that I forget about, which is actually what life is, apart from escaping into an imaginative space and doing the psycho thing and creating stuff. What about you, Ali?

AB: I love making lists. My day usually starts sitting at the dining table having breakfast with my two young girls, who are five and seven. After we’ve eaten, we draw and talk. And then I get myself excited and start making notes and lists before taking them to school. I come back and then start off where that spark began early in the morning talking about whatever. It’s not that creativity happens right away. There’s a lot of sitting and looking. Somebody once wanted to record me, like, “Oh, can we record you making your paintings?” And I said, “It’s going to be the most boring thing, I’m just going to be sitting on my chair looking at a painting for three hours and then maybe get up and do something and then go read and then come back again.” I don’t have a set schedule to know when it’s going to happen. I just know I have to show up. That’s the most important thing. And whatever happens in the studio revolves around the painting. It’s sitting there staring at me, I’m staring back at it. And then maybe I’ll sit down and a part of a painting will just say something to me, and I’ll perhaps begin there. That’s pretty much every day.

OM: If you’re sketching before you paint is that like note making or outlining what you want to do?

AB: I think it’s more like trying to grab all these abstract thoughts and putting them in one place. I may go from a white canvas to an explosion of fragments—which can happen in a day—but then it becomes a matter of looking into the fragments and trying to see which parts speak to me. It’s like clouds where you see something and try to grasp it before it changes to something else. So this notetaking— everything that I’m reading, thinking, current events, art that I’ve seen, conversations I’ve had—is a way to ground all these abstract thoughts that are trying to escape in a million different ways. But that doesn’t mean that all these things are necessarily going to end up in the painting. Do you write in fragments like this?

OM: I’m not sure if this is similar, but each novel feels like a kind of experiment with a process. And each project is a development from the last one. I always feel I’m learning something: OK, don’t do this next time. And maybe I’ll set myself a limitation so that I can’t do something and I’m forced to do something else. If I was going to explore a tone or a scene, I might write around it in different ways before going into the document. This is happening more now, in the project that I’m currently in, than it used to, because I’m dealing with a handful of characters and I keep finding myself writing things about them because I’m still figuring out who they are and what parts of their stories need to be included. And then realizing that it’s in a completely wrong place and moving it, and then having to redesign that old space to accommodate that fragment. And that’s kind of how the storytelling rhythm is established, by accommodating these pieces of people while I am crafting a narrative that connects them, if that makes any sense.

AB: I have this sort of synesthesia thing where, when I start a painting, it’s just sounds, and that’s how I’m able to even know how to control the rhythm and where what should go where. In your recent book, Lapvona, I could feel this musical thing underneath that just carries you. I named one of my paintings after a quote by Kafka where he said that books should be the ax to the frozen sea within us, like they should just stab us and wound us to wake us up. And I feel that’s what Lapvona does. How do you think about sound? Is it just something you feel, like the rhythm?

OM: I grew up with music, in a family where both of my parents were musicians and also teachers. So there was a lot of other people’s music in my life. And I really think that the beginning of my development as a writer was as a pianist, and this idea that if you’re learning something new, you can’t play it right away. You have to practice it in pieces in order to understand it. It’s not, “Can I get my fingers to do all these things at the same time?,” but “How do I understand this melody?” And then, “How do I understand that melody in contrast to this harmony and then the bigger structure of the whole thing?” I used to plan books narratively because I felt like a novel was so long and it needed so much integrity that I saw the process of writing a novel much like filling a container with a very specific shape. And it was my job to show up and fill it. And because there was this preordained shape, that everything that would fill it, that wouldn’t leak out or transform somehow, was correct. And I’ve kind of shifted away from that—not that I feel like my work is becoming much more improvised, but I am forcing myself to not assume a shape, and letting the writing itself dictate where the book wants to go, which is a much more insecure process for me, and actually way more exciting.

AB: For me that’s the most exciting part about painting, letting the work dictate where it wants to go, because it ends up telling me things I didn’t know before I started.

GRAND: One commonality in your work is the role of the grotesque in what you create. Is that something you actively think about?

“… when I start a painting, it’s just sounds, and that’s how I’m able to even know how to control the rhythm and where what should go where.”

–Ali Banisadr

OM: The grotesque isn’t necessarily the way that I think of what I am doing. What is interesting to me is other people. And when I’m writing another person, I have to get really close and there’s something repulsive about a person in general, something about the separation between people, and the disharmony, that feels like a gross and violent thing. And it feels important for me when I’m writing about a character to embody them with that in mind, so that I can capture the real effect that they have as a being, and also understand their need to impose on the world by existing. And I don’t even think repulsion is bad, but I find it useful, personally, not simply as an artist in a formal way, but as a person. Disgust has been an enormous theme in my life. I’m 41 and I’m finally, maybe, not a teenager anymore. But I’ve been a teenager my whole life and being disgusted was a big part of my response to the world. And it saved me from hiding from it because it was a way of reacting. Honestly, at this point, I’m not even disgusted, I’m just hiding. It’s not that great. I kind of miss that sort of revolt, just being revolted by things and all that energy that you get from that feeling. I actually miss it. Maybe that’s why I have so much of it in Lapvona.

GRAND: Was there a moment in your childhood when that sense of repulsion became a salient part of how you viewed the world.

OM: I always felt disgusted by myself. Not as much anymore, but definitely in adolescence. And I think it has a lot to do with mortality and death. I kind of resist the psycho-analysis because it makes me feel like I’m just this trite, compulsive person who can’t let things go. But I do think a lot about the difference between a body that’s alive and a body that’s dead. And the processes that are happening internally and also what happens to the person’s mind. That’s always been a big deal for me. And maybe the most important thing that I have been obsessed with is: What does it mean to be alive and what does it mean to be dead? What is it comprised of? Knowing that your body can be alive and constantly renewing itself, and then it can be infested with maggots. That is fascinating to me as part of the life cycle. That we can feel vanity about the living body is also fascinating to me, and the way that we become so attached to an idea of ourselves that feels crucial because the ego is part of how we stay who we are. And that in the end it doesn’t really matter. It’s so funny.

AB: Sometimes I feel like I view society in the way an alien that landed on earth might see us, where I’m just looking at people and it’s such a grotesque, pointless thing that’s happening in front of me. And I think that’s how I could relate to an artist like Bosch or Bruegel because I feel they were social critics in their time, observing human behavior. Goya too. Thinking about human folly and what we’re capable of doing to each other.

GRAND: I wonder how your Iranian background, and particularly the revolution of 1979 has shaped your creative consciousness?

OM: I was born a couple years after my parents moved to the Northeast US. I’ve never been to Iran. My father has been back once in 42, 43 years. I think it was a really depressing experience.

AB: It was for my mom, too. When she went back, she was just like, “I don’t recognize this place.” She was crying every day.

OM: I’m so grateful that I didn’t have to experience it firsthand, unlike both of my parents and my sister. That exodus was, I’m sure, incredibly traumatizing. But what I do have is just this big question mark about where my family comes from—that side of my family, that piece of me—and also this sense of being at home and displaced at the same time, feeling like I belong here on one level and also that I’m just a visitor on another, all of the things that would be helpful to make someone feel uncomfortable, which is exactly the position I think I’ve needed to be, in order to be a writer—to be uncomfortable. The impetus for making anything for me is that I’m uncomfortable. If I was happy and comfortable I’d be working to make other people happy and comfortable. Maybe I’d be a nurse or a masseuse.

GRAND: How about you Ali? You were in Iran during the war, so that’s a different experience to Ottessa.

AB: I was three or four when the revolution happened but of course, as a kid you don’t know any better. Basically, all your childhood life is growing up in, first the revolution, and then the war, which was eight years of bombing. We moved to America when I was 12, to San Diego of all places. My idea of America was New York and then we get to San Diego and it’s all malls, it was just so weird to me. I didn’t understand suburb life, and I didn’t speak the language too well, and I didn’t really think about what happened in Iran. I buried it because everything was horrible, not only the revolution and the war, but people, too. Everybody was in a bad mood except for your grandmothers who cooked for you and loved you. I didn’t really think about it until way later, when I was in art school when I visited the D-Day sites in France, and it triggered memories of ruins and war scenes. And then I decided to make these charcoal drawings based on memory, on sounds, because as a child much of the experience was the sound of war—the explosions or vibrations. And drawing was a way of trying to understand these things that our little minds couldn’t even comprehend. It’s never that I’m trying to paint a certain time or place. It could be anywhere, it could be anytime. It’s a mixture of different figures from different times, sort of like coming together in the paintings really. But it definitely must have some kind of an impact.

OM: That’s so interesting. I wanted to ask a question, but I hadn’t really figured out what it was. And it was something to do with sound and movement in your paintings. I kept wondering, in your paintings: “How long is that? Is it a second? And is this all happening at once? Or is this a year?” Somehow it has this feeling of an incredible expanse of time and space, and then a snapshot at the same time. What you’re saying about sound, and how it echoes in memory, makes so much sense for me, thinking about the rhythm and the use of time and movement in your work. Does that resonate at all?

“And drawing was a way of trying to understand these things that our little minds couldn’t even comprehend. It’s never that I’m trying to paint a certain time or place. It could be anywhere, it could be anytime.”

–Ali Banisadr

AB: It’s like things are in the middle of transformation, and you’re trying to catch it, this metamorphosis. It’s like an explosion of stuff, but it’s just slowed. And sometimes I feel like it has to do with the way I make them, where there’s this fast sort of explosive energy underneath everything, but I’m also developing moments within this infinite bang. And then there’s sounds, also, from each character, which I can even taste in my mouth. I’m super sensitive to it when I’m making it, as if it’s part of me or I’m in it. I was going to ask you about this also. These characters that I create, I can see traces of them from imagination, but also from all the visual things that I feed myself. I look at one figure and I’m like, “Oh, this is partly a Mesopotamian God, and partly from that color I saw on that Titian painting, and partly it reminds me of this person, but it’s all those things in one, as I’m making them. As a writer, do the characters end up being a combination in that way, say somebody in your personal life, but maybe you’re also thinking about a story by Borges, or something you saw. Like Villiam in Lapvona, I know that guy. It’s an archetype of the type of corrupt king who doesn’t give a shit and he’s just consuming all, eating all the time.

OM: What was weird was I had a lot of different things in my mind and for Villiam there was this sense of a contradiction between someone who was emaciated and starving and who could never eat enough was really interesting to me, and the idea of this person being the most powerful and how he would be encouraged in this unfortunate way to believe in all of his delusions. I was like, “Oh, that’s a new character for me.” And I was like going through a bunch of stuff and I found this print that I did in high school, and I was like, “That’s Villiam.”

AB: That’s what I’m saying! These things exist within you, right? My characters show up in other paintings too. It’s like, who is this? It keeps changing of course. And it has different meanings depending on the painting. This is an authority figure. This one is like a funny jester. It’s just interesting that we carry these multitudes of characters within ourselves and they show up. It was in your painting from so long ago and then it shows up here, in your book.

GRAND: Where was that painting? Was it something you just held onto?

OM: I think I found it when I was visiting my mom back at home. I was actually really like into printmaking in high school. I went to this really cool school, with less than a hundred kids. And they had a dance studio and a photography studio and a printmaking studio.

GRAND: Ottessa, do you read while you write?

OM: No. And I very rarely read fiction these days, for the same reason that I can barely listen to music and it’s that I am so hypersensitive and also an absolute control freak about what I choose to consume. I’m obsessed with stasis and I get very uncomfortable and upset when I’m emotionally moved, which happens almost immediately upon looking at something, listening to something or reading something, and then I’m like, “How will I ever be the same?” I mean, this is like half a paragraph in, you know.

AB: You mean your mind goes to a million places of what is possible with the thing you just consumed?

OM: And also my heart. I’m having feelings that I didn’t put there, you know? I have an intense rigidity around that because I feel like if I give myself to that experience, I’ll lose control and won’t be able to go and have the same sort of agency that I need in order to do my own work. It’d kind of an issue because it keeps me from enjoying things. But weirdly, it’s less of an issue with film. So I watch a lot of film and love film, and I’ve been working in film for four or five years, and most of the writing that I’m doing now is for the cinema. I co-wrote an adaptation with my husband, Luke Gobel, also a writer, an adaptation of my first novel, Eileen. It was an incredible experience and I feel so lucky that it turned out so well.

GRAND: Ottessa, you’ve said that you have no personal religion but understand God as the intelligence of the universe. Can you both expand on that?

OM: My spirituality is, unfortunately, limited to my creative practice, but I find it very hard to have faith outside my work sometimes. I don’t really take any credit for what ends up being in my books beyond my willingness to show up and write them. I could see the divine in almost anything, even stupidity, but I really do have faith that there’s something bigger than me that’s sort of conducting the electricity, and sending ideas and impulses into me, like I’m some kind of translator or transmitter.

AB: I also see it as energy. It’s like the story of Simorgh, this mythological Persian creature, in the poem by the 13th century Sufi poet Attar, about these 30 birds on a journey to look for Simorgh, this sort of legendary bird, maybe God, that has all the answers. And when they get to this place where they’re supposed to meet Simorgh, someone tells them, “All 30 of you, together, are Simorgh.” They’re basically looking for themselves, and we are all part of this sort energy. We’re all fragments of it.

GRAND: What have you read this year that has stood out for you?

OM: I read Leonard Cohen’s early fiction. He was obviously an incredible poet and writer but his impact on me was as a musician. And so to read the fiction that he was writing in his early twenties was fascinating because it’s similar to what we’ve been saying—you can see the seeds of things planted so long ago, and then you can also see where he started in his immaturity, and in the immaturity of his fascinations, and how some of those continued and became more, I don’t know… interesting. It’s not a masterpiece, but there’s so much young talent and beauty in it. And then also all the stuff that is really kind of weird, a lot of his feelings about sex and romance.

AB: For me, two books stand out. One was a book for a show that I saw in Venice at the Peggy Guggenheim collection. It was called Surrealism and Magic, and it was about how the surrealists were interested by alchemical engravings and renaissance magic and all the occult stuff like astrology and tarot. And the other book is Frances Yates’s book on Giordano Bruno and the hermetic tradition. She also wrote a book about memory palace, which was a way for Romans and Greeks to memorize things. They would imagine, say, a house or a room and then anything that they would come across, they would put it on a bed or in a bookshelf. And that’s how these polymaths were able to use this memory palace—all the stuff in their memory would exist in this place because they could visualize it. And Giordano Bruno was like a philosopher mystic, so this book talks about, basically, three guys who were sort of responsible for the Renaissance, really. And then of course, they burned him at stake because he was going against the church by saying that to get to the truth, you need to combine everything together—Greek philosophy, Kabbalah, Zoroastrianism, Hermetic teaching—all these different things. So yeah, cancel culture.

Ali Banisadr (b. Tehran, Iran, 1976) lives and works in New York City. The artist has recently been the subject of solo museum exhibitions at the Museo Stefano Bardini & Palazzo Vecchio, Florence; the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum, Hartford, CT; the Benaki Museum, Athens; Gemäldegalerie, Academy of Fine Arts, Vienna, and Het Noordbrabants Museum, Den Bosch, Netherlands. In 2013, his work was included in “Love Me/Love Me Not, Contemporary Art from Azerbaijan and its Neighbors,” The 55th International Art Exhibition, Venice Biennale, and “Expanded Painting,” Prague Biennale 6.

Banisadr’s work is included in significant public collections worldwide, including the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY; the British Museum, London; Centre Pompidou, Paris; Het Noordbrabants Museum, Den Bosch, Netherlands; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; Museum der Moderne, Salzburg; the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, CT.

Ottessa Moshfegh is a fiction writer from New England. Her first novel Eileen won the PEN/Hemingway Award for debut fiction and was shortlisted for the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Man Booker Prize. Her next three novels, My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Death in Her Hands, and Lapvona were on the New York Times Best Sellers list. She now resides in Southern California.