On occasional Saturday mornings, Kasmin shares essays and interviews from both archival and newly-printed publications that expand critically on the work and practice of gallery artists. The below essay is reproduced in celebration of Los Angeles-based Theodora Allen's first institutional exhibition, Saturnine, which opened at Kunsthal Aarhus in Denmark in Spring 2021. The accompanying publication, written by curator Stephanie Cristello, straddles criticism and prose and constitutes the artist's first monograph. This extract from the book explores the artist’s emblematic use of symbols as well as the cultural history of Saturn and Melancholy from ancient myth right through to the present day.

On March 11, 2019, the largest migration in history of Vanessa cardui, a species of butterfly colloquially known as the Painted Lady, took flight across Southern California. At the height of the spring migration, the saturation of butterflies in the air turned blue skies into a type of glinting expanse— from La Cienega Boulevard to across the Interstate 105—suspended like the particles of a snow globe. (2) The familiar sight of migration, a constant cascading movement, had fallen out of recent memory; years previous, the breeding of Painted Ladies was in steep decline and numbers were reaching historic lows due to drought, which had led to less desert flora. Yet, on February 14, 2019, winter rains in the Coachella Valley measured more than the collective annual rainfall years prior. An estimated one billion butterflies migrated from the deserts of Northern Mexico across Southern California before settling to breeding grounds in Oregon. A particularly fierce El Niño was credited for assisting the phenomenon.

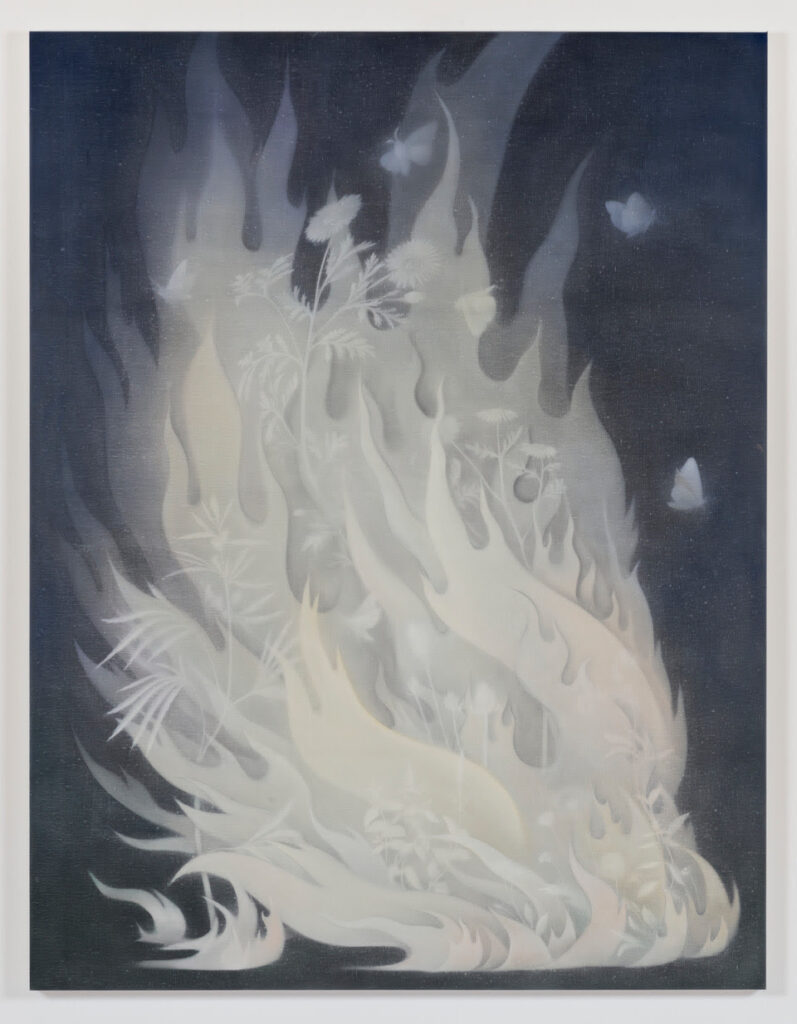

Climatologists speculated that the heavy spring growth would make for dry fuel later in the season. In October of the same year, the warning proved true. A landscape once consumed by butterflies became engulfed in flames and the same hills of golden poppies were devoured in the inferno. (3) Progressively worsening wildfire seasons and an increase of acreage burned over longer periods of time is an impact of climate change weathered by all Californians. As with the Painted Lady migration, greater abundance leads to greater loss.

In September of 2020, in the midst of a global pandemic, images of orange skies flooded our vision. Unable to travel, landscapes beneath a pale and sullied auburn passed through our phones, as if the poppy’s pigment was mixed with the greyish white of the smoke itself. The atmosphere did not smolder as it appeared to, cold ash blanketed everything, and the smell of burning pine drifted across the continent.

In these three instances of orange—the wings of the Painted Lady, the hills of California Poppy, and the aftermath of the wildfire skies—each turn to black. During migration, the silhouette of the Painted Ladies’ mottled marigold wings could belong to almost any genus; a shadow play, floating through the sky like an inked animation. Across the rolling mountainsides, the paper-like petals of the state flower transmuted into puffs of smoke. While the fires raged and the sun set in an apocalyptic glow, the moon would shine a pallid apricot against the muted blackness.

Oh, but California, California.

(4)

Jekyll and Hyde plants that can be used for good or for ill. Killer or curer, sinner or saint.

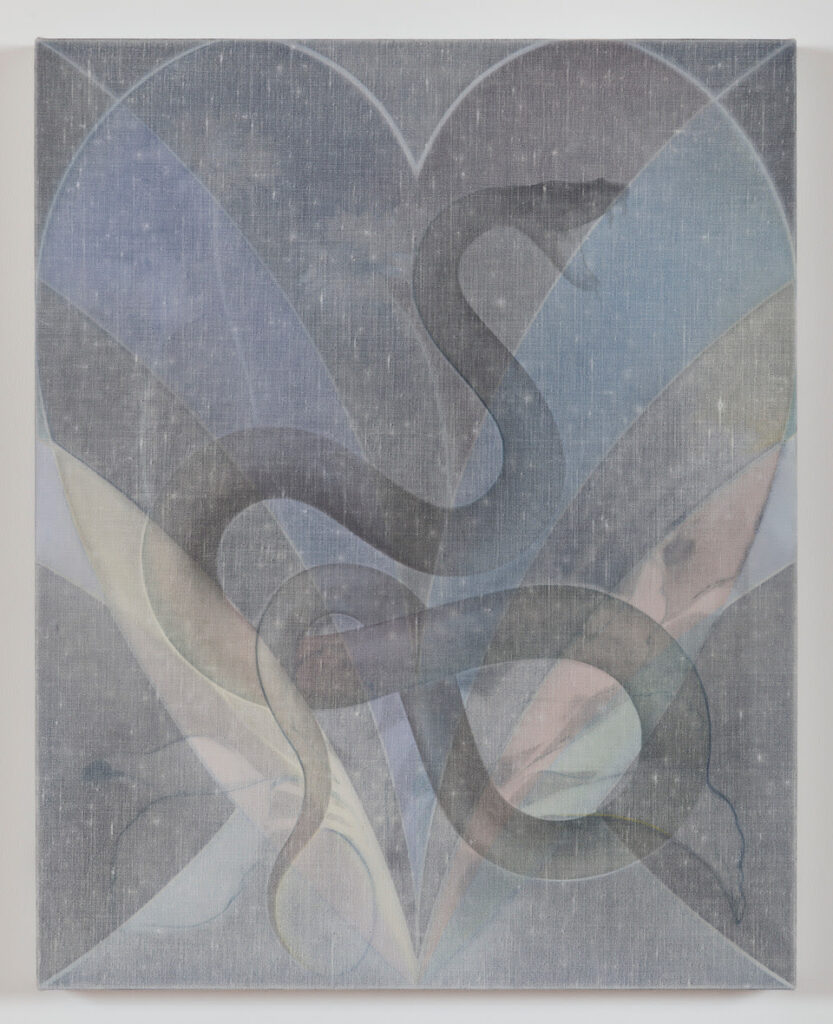

In Theodora Allen’s work, cycles of loss and regeneration point toward the artist’s interests in the making and unmaking of nature. Weaving together disparate images and events, Allen often uses color as an aesthetic cue to reveal histories, associations, and relations between a given subject and its aesthetic use as a motif. These depictions within the artist’s repertoire have ties to language whose associations reveal the depth of metaphor. For example, the terminology used by wildland firefighters to track the spread of a blaze adopts the anatomy of a serpent: the “head” of the fire moves fastest, while the “tail” is the spread at its slowest, often the point of origin. The flame of this tail, furthest away from oxygen, glows a delicate blue. As with Allen’s paintings, it is often with blue pigment that the artist depicts her most distilled, elemental, timeless images: emblems that do not burn but glimmer. Fugitive to immobility, her works picture a series of dialectic oppositions: light where we imagine the cloak of darkness, distance when we expect the singularity of closeness, protection where we envision danger. Through a sequence of material and conceptual inversions, Allen’s work resists contradiction in favor of co-existence.

Hey blue,

There is a song for you.

(5)

Blue: the color of frost, of the sea, of a flame at its hottest temperature. Of the sky, of bruises, of clouded apparitions, of blindness. Of all perceptual hues, blue is arguably the only color in the spectrum that embodies such divergent interpretations. Blue articulates an index of intimacy and detachment, heat and iciness, the personal and the universal. It is the enduring presence of blue in Allen’s work that lures us. Her specific preoccupation with blue is not merely aesthetic, it is also culturally and emotionally versed. It is a signifier of the self. In his 1810 book Theory of Colours, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe writes, “we love to contemplate blue, not because it advances to us, but because it draws us after it.” (6) In her 2006 book A Field Guide to Getting Lost, Rebecca Solnit writes, “The term blue comes from an Old English word for melancholy or for sadness, blue moods, blue devils, the blues, first tracked to 1555 in my etymological dictionary.” (7) As William H. Gass writes in his 1976 book On Being Blue, blue is “most suitable as the color of interior life.” (8) Across centuries, blue draws us in.

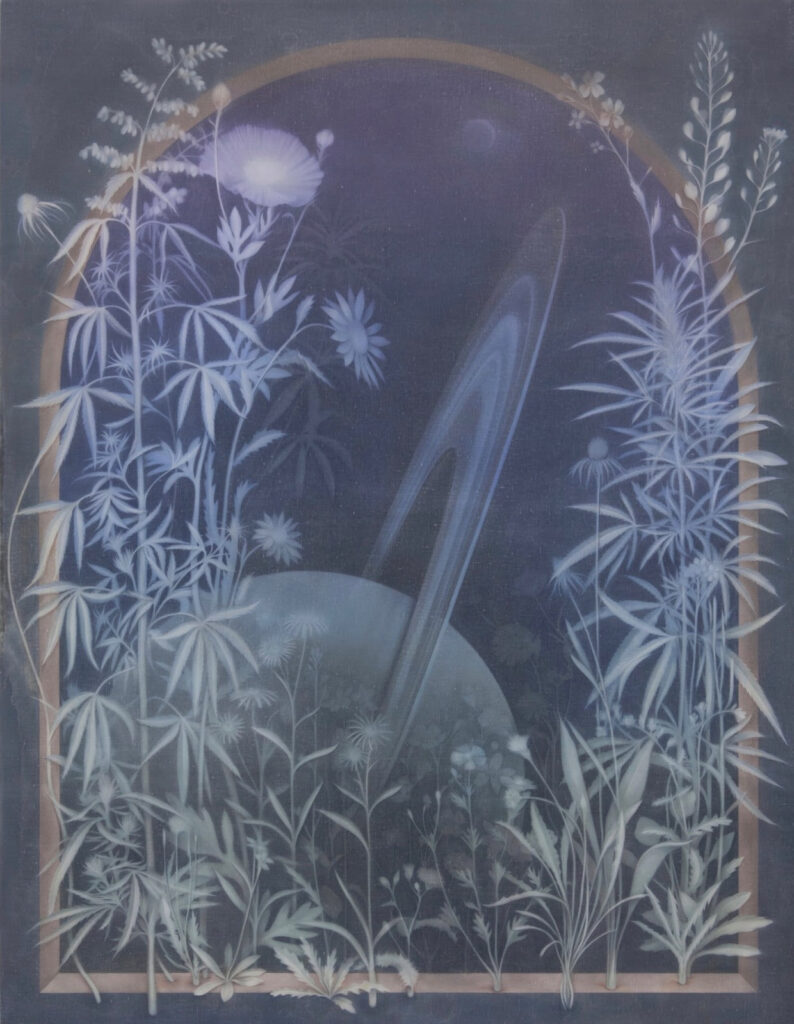

One exhibition in particular pulls us into the blue. In Allen’s 2018 show, Weald, at Kasmin in New York, the space was divided into two series: the first, showing a number of intimate-scaled paintings that each centrally portray hallucinogenic plants, entitled Shields; the second, a smaller group of large-scale works entitled Monuments. Of the immediately recognizable species of flora featured in the seven works that comprise Shields, we see the morning glory and the opium poppy. The pale coniferous paper-like roundel of the petaled vine and the deep flush of the black-centered field flower are both reduced to the same light-emanating, inverted blue. Reminiscent of processed cyan, the paintings hover between the almost believable soft silvery rendering of moonlight and the redacted shadow of a negative image produced by early photography. Their manner of representation is either too detailed or too abridged to nest comfortably in either category. Further, housed within brushed bronze frames, the canvases are removed from the exclusive language of painting. They hold the potential of being imported into the realm of décor and photography alike. Encased within the motif of the shield, the representations of plants adopt the language of familial crests. The double frame seeps into the exhibition title, Weald, which presents an anagram of interchangeable archaic words. On the one hand ‘dwale’ from Old Norse, which translates to a deep sleep or trance, while ‘weald’ hails from the Middle English term for forest. As the exhibition text positions, “one is landscape and the other is mindscape.” The blue forest, the blue mind. The words feed into one another.

Underneath the skin,

an empty space to fill in.

(10)

Research into the various plant species selected for Allen’s Shields reveals glimpses into the histories of their psychotropic effects. Each entheogenic use of botanical carries, to varying degrees, the weight of disproportionally poisoning women throughout the ages in the name of sin or beauty. While the effects of opium are more widely known, the inclusion of the morning glory would come as a surprise to those unfamiliar with the history of its use. Known as Heavenly Blue, the ingestion of morning glory seeds induces a dream-like state closely related to LSD. The Aztecs used the seeds for divination rituals. (11) Henbane, whose wide use for decoction dates back to 1265, produced hallucinations and sensations of flight, which eventually lead to the witch-hunt.

In the case of Belladonna, also known as “deadly nightshade,” Italians in the Renaissance frequently administered the poison as eye drops to dilate women’s pupils in order to achieve a more seductive appearance. Many of them went blind. The exotic pinwheel bloom of Devil’s Snare, led to deliriant states and a complete inability to differentiate reality from fantasy and to feel as though they were flying: hysteria. (12) During the Spanish Inquisition, women experimented with the plant were said to have “danced with the devil”—forced to confession, they were burned at the stake. (13) Plants of love, hate, and dreams. Aphrodisiacs, poisons, and deliriums. As Allen describes, “Jekyll and Hyde plants that can be used for good or for ill. Killer or curer, sinner or saint.” (14) And yet, each of these plants are depicted as shields, not as images represented within crests. What, then, are they protecting?

So I hurt you too, then we both get so blue.

(15)

The origins of melancholia, that feeling we call “blueness,” is often described in similar terms of dependency with a language of addiction.

The moth flies closer to the flame. As Maggie Nelson writes in her treatise on blue for her 2009 book Bluets, “For Plato, color was as dangerous a narcotic as poetry. He wanted both out of the republic.” (16) As a form of pharmakon, he concluded that experiences of color were a type of drug. The origins of melancholia, that feeling we call “blueness,” is often described in similar terms of dependency with a language of addiction. It is something one has—a predisposition, a disease—that develops reliance. Published in 1964, Saturn and Melancholy by Raymond Klibanksy, Erwin Panofsky, and Fritz Sax1 traces the lineage of sadness in protopsychology from antiquity to the twentieth century. Before it was a temperament, melancholy was an illness. As a cause of black bile, a notion that came from empirical medicine, melancholy was said to be a malady of the spleen caused by the influence of Saturn. (17) Adopting more contradictions and complexities as centuries passed, the illness gradually transformed into a flexible doctrine, synonymous with not only sadness or inaction but also of talent, of genius (melancholia generosa). With this possibility for a positive outcome, which could lead to artistic inspiration, patients wished to fall into their melancholic tendencies, even if it meant madness. It became the disease of artists. Developing a resistance to a remedy was sought after in the name of creativity. For the melancholic, protection meant the freedom of being exposed to obsession. The antidote was the poison, a therapy of curing same with same. What hurts us draws us nearer.

*