On occasional Saturday mornings, Kasmin shares essays and interviews that expand critically on the work and practice of gallery artists. The below essay on Elliott Hundley (b. 1975) by writer, curator, and educator Anuradha Vikram was commissioned on the occasion of Hundley's first solo exhibition with Kasmin, on view from September 9—October 23, 2021. Explore the works in our online viewing room.

When I meet with Elliott Hundley in May to discuss Jean Genet’s The Balcony, on which his current suite of paintings at Kasmin is based, there are certain basic questions about the play that we find ourselves unable to answer with confidence. Questions like, “What’s this play about?” and “Where does it take place?” On its surface, The Balcony is about gender, sex, and power, and it takes place in a private sex club. We meet Irma, the proprietress, and a series of men with varying levels of social power who visit to indulge their fantasies of greater and more absolute power. These fantasies are staged by Irma and the younger women who staff her establishment. Outside the club, we are told, there is a revolution underway. The Bishop (a client whose fantasy is to absolve the working girls of the sins of his own creation) runs afoul of Irma when he overstays his hour, having parked his car in a conspicuous place that might draw the rebellion’s attention to this pleasure-house for the elites.

The name of the club is “The Grand Balcony,” called a “brothel” by Genet and in my 1966 translation by Bernard Frechtman, but closer to a contemporary BDSM dungeon than a bordello in terms of the power-oriented aspect of the fantasies put on display. Irma’s rules prohibit intercourse: a boundary that one young woman, Chantal, has crossed, resulting in her exile to the war outside. One woman complains of mistreatment by the clients, to which Irma responds that she must accept the real pain because it makes her role-playing as a victim more convincing. The charge of the fantasy exchanges is sharpened by the real gender and class dynamics that reinforce the dominant-submissive games these men pay to play.

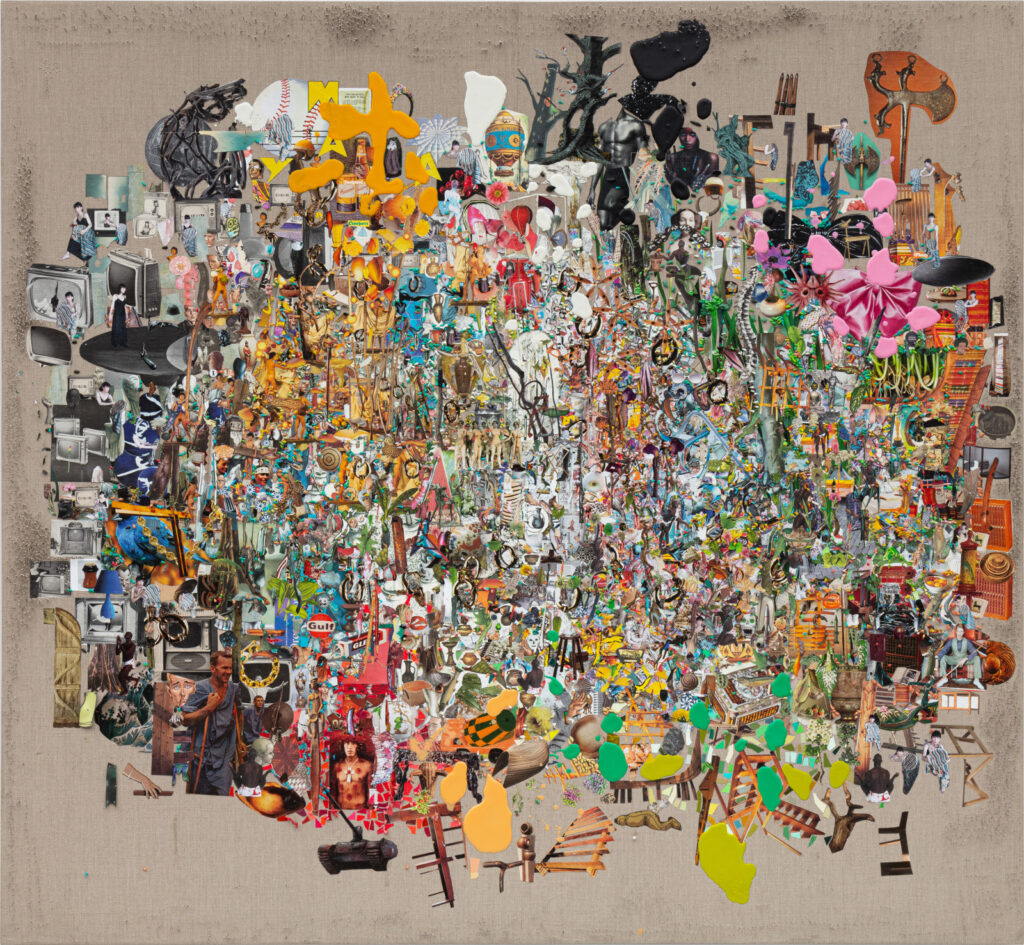

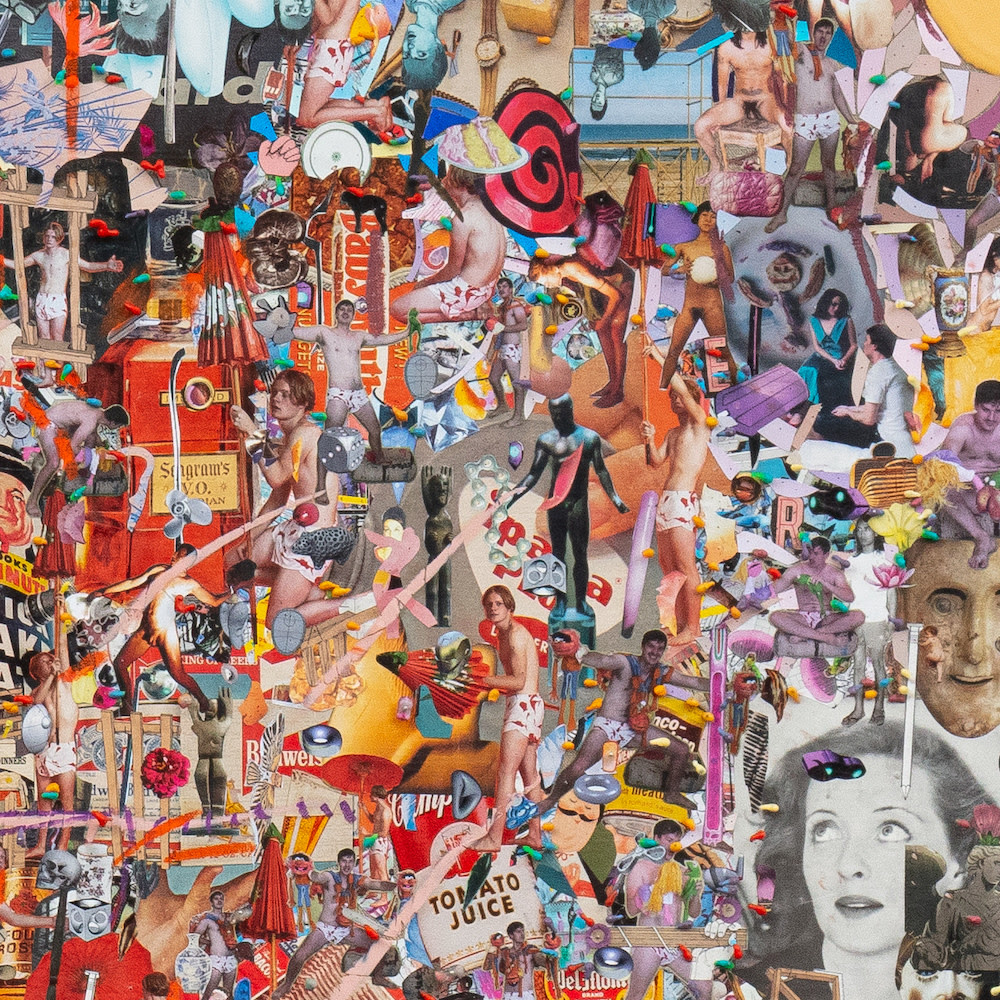

In Elliott Hundley’s paintings and drawings, there is a concurrent breakdown in narrative to the one that readers of The Balcony experience. Attempting to read these images in a linear fashion will only lead to frustration. Hundley’s assemblages of materials, collaged photographs, and paint are densely packed with information according to a personal logic that need not translate to the observer. Instead, the works generate an endless series of shifting impressions prompted by surprising invocations, references, and juxtapositions that build an atmosphere of complexity bordering on chaos. This sensibility is closely aligned with Genet’s, as the artist visually abstracts the narrative elements of The Balcony so that the breakdown of rational sense feels absolute.

“Hundley’s assemblages of materials, collaged photographs, and paint are densely packed with information according to a personal logic that need not translate to the observer.”

Elliott sends me an email in July: “I know what the one ‘real’ thing is.” We are co-conspirators attempting to unravel mysteries from the not-so-distant past. The mystery of Genet’s underlying message to the reader compounds the mystery of how a sixty-year-old play can speak so chillingly about our present moment. Reality is a fungible concept in The Balcony. The Bishop, The Judge, and The General are all archetypal fantasies of male power that The Grand Balcony’s clients seek to fulfill. Authenticity is desired in every detail of the fantasy, from mud on The General’s boots to verification of The Thief’s crimes as witnessed by The Executioner. Importantly, each of these roles are supervisory, such that the cruel consequences of these leaders’ arbitrary decisions are carried out by others. The only man in Irma’s employ is The Executioner, whose job is to administer the floggings that The Judge can prescribe but cannot inflict himself. He must strike the woman firmly enough that The Judge is convinced of her punishment, yet lightly enough that the woman is healed and agrees to perform the role again the following week. The clients desire to watch those in their charge suffer for reasons that they deem to be righteous based on systems of authority that they aspire to design and control.

Hundley’s drawings and paintings are largely titled after characters in the play and their social roles: Bishop, General, Judge, Madam, Queen, Rebel, Sinner, Thief. Bishop is marked by cardinal reds, which visually recall that character’s costume, an oversized ecclesiastical cope. We find myriad details, most distinguishable at the edges: a cigarette pack, a high-heeled shoe, a Miller High Life label, all in shades of crimson. Who is the judge, and who is to be judged? “THINK,” implores a small sign that appears to hang at the base of the painting. Judge includes numerous references to classical aesthetics, eugenic measurements, remnants of the human body like dental molds, colonial ceramics, Olympian athletes. The palette here is pale yellows and pinks, which give the work a fleshy, lipid pallor. Madam is rife with textiles and masks, referencing the construction of fantasy that is Irma’s profession. Queen is ringed with images of mid-century televisions and books, which speaks to the role of publication and broadcast in creating and perpetuating our myths of power. Thief includes mirrors—Irma’s preferred mode of set dressing—and images of African artifacts alongside a series of photographs of a Black man (a friend of the artist) that speak to the complex and psychologically damaging nature of cultural appropriation and how it can appear even in our personal relationships, regardless of intention. What makes these works effective is that the messages contained within are intuitive, never explicit, and each viewer will interpret them according to their own perception, identity, and personal frames of reference.

Where does the play take place? Genet is associated with the existentialism of his friend and advocate, Jean-Paul Sartre, whose play Huis Clos (No Exit) occupies a similar kind of liminal space. In Huis Clos we receive the timeless adage “L’enfer, c’est les autres” (“Hell is other people”) as Sartre gradually reveals to us and to his characters that they have reached the afterlife and eternal punishment of their own petty making. The Balcony could also take place in Hell, not the Limbo level of Sartre but the second level, Lust, in Dante’s parlance. As the story unfurls, we find ourselves still lower, traveling through Gluttony, Greed, Anger, Heresy, Violence, Fraud, and Treachery. Importantly, even the few scenes that take place “outside” The Grand Balcony, where we meet Chantal and her rebel lover, Roger, represent aspects of this hierarchy, as well as elements of fantasy. Chantal comes to understand that her role is the same outside as it was inside, only now as the symbolic repository of the rebellion’s power rather than that of just one man. Roger, meanwhile, is undone by his desire to maintain a populist fantasy, albeit a leftist one, that serves his longing for power and control at Chantal’s expense.

Genet’s 1962 note “How to Perform The Balcony,” which Elliott shared with me, makes clear that the play is concerned with who holds power and who wields it, irrespective of political association, and that he means to show how patriarchy and male domination can be packaged in a way that transcends gender. Genet’s note suggests that Carmen, Irma’s bookkeeper and the former Virgin of Guadalupe, might in fact be directing the action, as she assists her employer in making her own fantasy transformation from severe businesswoman to romantic leading lady in Scene Five. In this scene, Irma explains that each client brings their own fantasy, fully formed, with specific details that confirm that dream’s veracity. Her role is only to facilitate these dreams, in every permutation: the Studio of the Hangings, the Studio of Perfumed Foundations, the Urinal Studio, the Studio of the Beggars. Like Irma, Elliott Hundley has placed an authentic detail in the exhibition at Kasmin. At the center of the gallery hangs a large sculptural Chandelier adorned with neon, which makes reference to Genet’s opening stage direction: “On the ceiling, a chandelier, which will remain the same in each scene” (Genet 7). By placing this tangible physical object in the space, Elliott has given us viewers our one “real” thing to make the fantasy ring with emotional truth. The ubiquitous presence of the chandelier reminds us that there is no true separation of the realms.

“So what’s the play about? It’s about how there’s no outside to the culture of domination, no safe place where we can play at being revolutionaries, no way out but through.”

“The Chief of Police” is a spectre throughout the play. Irma fears two intrusions, that of the rebellion and that of the police, though she has bought off the latter financially as well as sexually. She is anxious about the police being called, as she tells The Bishop, but when The Chief of Police finally arrives, she addresses him as a longtime lover. The Chief of Police, for his part, has two concerns: maintaining order within his ranks in the face of rebellion, and ensuring that his leadership is sufficiently celebrated so that his role will finally become one of the recurrent fantasies for which Irma maintains permanent salons. Irma initially scoffs at this desire, explaining, “My dear, your function isn’t noble enough to offer dreamers an image that would console them” (Genet 47). The Chief has enough of an investment in Irma’s business that he has supplied her with Arthur, The Executioner, who functions as a bodyguard for the studios. When the rebellion breaks the frame of The Grand Balcony, first with an excursion to the front line with Chantal and Roger, then with the entry of The Envoy into Irma’s studios and their destruction, Arthur is the first casualty: reduced to a corpse and a stage prop by Scene Seven. This is where a series of transformations and equivocations begins.

Understanding the plot of The Balcony is not necessary to appreciate Elliott Hundley’s visual responses to its ideas. These paintings recall Irma’s declaration, “I wasn’t born of the marriage of the moon and a crocodile, I’ve lived among the people…” (Genet 65). Irma states this as she is being courted to assume the symbolic role of Queen, whom the Envoy cagily reports is deceased, but whose image must be resurrected for the social order to be maintained. As Irma becomes The Queen, the confusion of symbolic and real power in The Balcony is absolute. The absence of the leadership class is resolved by employing the fantasists to take up their roles for real. Are they dead, or are they retired? The Envoy obfuscates the question of whether the original Queen has died or withdrawn from her responsibilities: “The Queen is embroidering, and she is not embroidering” (Genet 85). The Chief of Police admits, “As long as I’ve not been impersonated, because after that I’ll just sit back and take it easy” (Genet 82). Is the desire for authenticity also the desire to inflict and ultimately to experience death, the one “real” thing? Irma tells Carmen of the “ultimate adornment” (Genet 37), the Mausoleum Studio, that will make her own fantasy house of illusions complete.

The Chief of Police asks the Bishop, “In losing everything they’ll come and lose themselves in me?” (Genet 86). In the finale, Scene Nine, Roger—who’s lost Chantal and been expelled from the rebellion—arrives at The Grand Balcony looking to inaugurate the role of Chief of Police inside Irma’s studios. Irma refuses, resulting in Roger’s violent self-castration. Photographers, dressed in the trendy fashions of the day, bear witness to these events of exclusion and self-harm. The Chief of Police accepts the grotesque turn of events as fulfillment of his immortality: “I’ve won the right to go and sit and wait for two thousand years” (Genet 94). Stripped of her protection, Irma drops the performance and shuts down the studio. She sends the Judge, the General, and the Bishop away to take up their roles outside or possibly get murdered. The social order has been overturned, and the economic cost of maintaining the fantasy has become too great, but The Grand Balcony is not gone, merely closed for renovation. There will always be a place for men to exercise their fantasies of power, Irma assures us, no matter who’s in charge.

So what’s the play about? It’s about how there’s no outside to the culture of domination, no safe place where we can play at being revolutionaries, no way out but through. This message is especially poignant for artists, whose livelihood is dependent on their deep personal insights, dreams, and fears, commodified for a ravenous public to consume. What hostile systems must we navigate, and how do these systems shape our desires?

Elliott Hundley’s works in the Balcony series show us afresh how our fantasies contain essential truths about the nature of power that governs our lives. He uses people he knows personally as his models, both men and women, and in doing so he exerts his power to take and use their likenesses in any manner that he chooses. Is the act of making art a self-canonization—a bid for the artist’s immortality? Genet may have thought so, given his embrace of Sartre’s moniker “Saint Genet” and of the mythologized version of himself that this narrative represents. In Elliott Hundley’s Balcony, the artist could be the proprietor of the house of illusions (Irma), its accountant and keeper of receipts (Carmen), the strong arm of the existing order (Arthur/The Executioner), or the ineffectual functionary who perpetuates the status quo (The Chief of Police). If in fact he plays all of these roles, at different times, then the artworks become perennially collapsing monuments to the fungibility of the self. *

Learn more about the writer below.

Anuradha Vikram is a Los Angeles-based writer, curator and educator. She is the author of Decolonizing Culture, a collection of seventeen essays that address questions of race and gender parity in contemporary art spaces (Art Practical/Sming Sming Books, 2017). She has written for Los Angeles Review of Books, ARTnews, Leonardo, KCET Artbound, Artillery, Hyperallergic, Daily Serving, Art Practical, The Brooklyn Rail, and OPEN SPACE (the SFMOMA blog), and the Paper Monument collection As radical, as mother, as salad, as shelter: what should art institutions do now? Vikram is a faculty member in the UCLA Department of Art and USC Roski School of Art and Design and serves as an Editorial Board member for X-TRA, an editor for MhZ Curationist, and an editor for X Topics, a subsidiary of X Artists’ Books. She has held curatorial positions at 18th Street Arts Center, UC Berkeley Department of Art Practice, Headlands Center for the Arts, Aicon Gallery, Richmond Art Center, and in the studio of artists Claes Oldenburg and Coosje van Bruggen.

All citations from Jean Genet, The Balcony, translated by Bernard Frechtman. New York: Grove Press, 1966.