On occasional Saturday mornings, Kasmin shares essays and interviews that expand critically on the work and practice of the gallery artists. Today’s offering marks the closing of the exhibition Alma Allen: Nunca Solo at Museo Anahuacalli in Mexico City. The below conversation between Alma Allen and the institution’s curator Karla Niño de Rivera will be published in the forthcoming exhibition catalogue from Kasmin Books.

The following conversation took place in a volcanic cave, hidden along a path in the garden of Museo Anahuacalli on November 8, 2022.

Karla Niño de Rivera: I knew who you were by sight before I knew that you were an artist—I remember your figure crossing the esplanade to visit the collection again and again. With your studio now in Tepotzlán, this exhibition was a natural step. I had seen it coming.

Alma Allen: Yes, ever since my first visit to Mexico City when I came here to Anahuacalli.

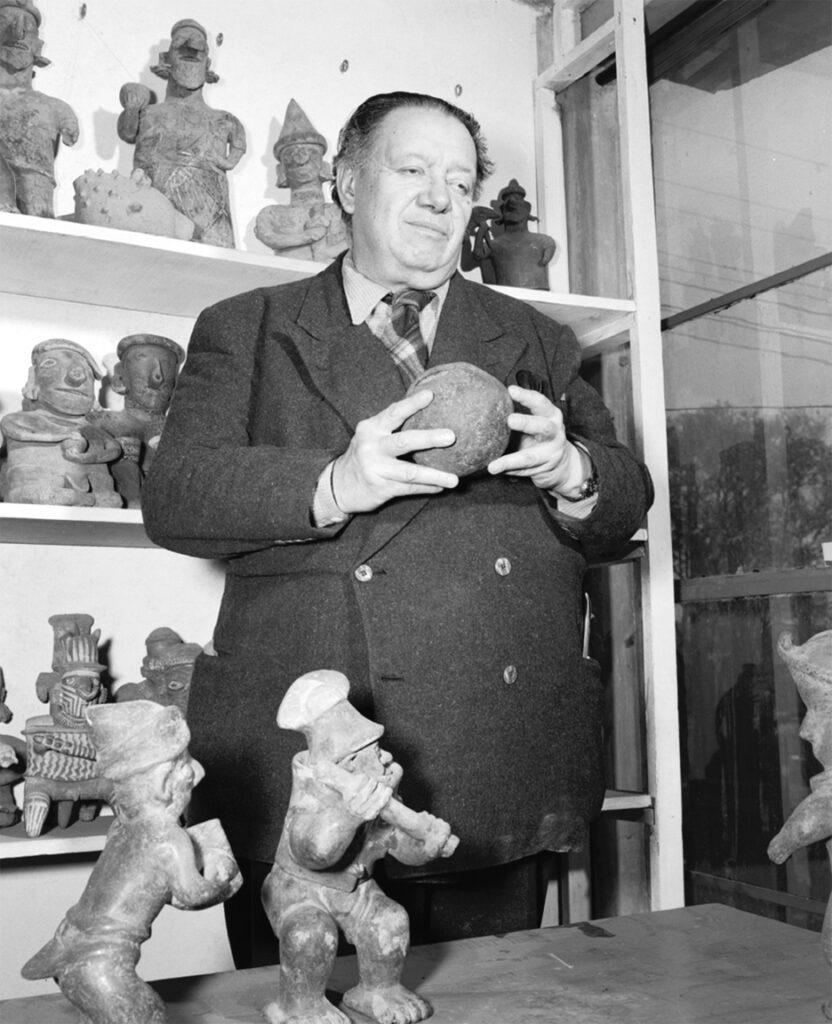

KN: Later, once we met and began talking, I realized how alike we were in our approach and understanding of the occult, freemasonry, and the Colima objects within the museum’s pre-Columbian collection. Your disposition reflects what constitutes the experience of the museum—not only in the political, social, economic, and geographic context of the structure, but also the inherent qualities that Diego Rivera possessed, which initially motivated him to build this temple and collection. I have noticed your interest in how history is portrayed throughout the space, precisely because it is confusing—everything in the collection is mixed, and nothing is chronological.

AA: I love that about it. There are no dates. It is totally obscure. I feel that many people go into a museum expecting to immediately read about what a given thing is, to have it explained, and it is best to never do that until you look. Here, at Anahuacalli, you cannot do this, and instead begin to relate things to one another, which allows you to see. Of course, even going by official dates, the span of the collection is vast. My work is closer in chronological time to the most recent pieces at Anahuacalli than those same works are to many of the older works in the collection.

I have never really felt that what I make exists only in the world of contemporary art, or even in distinction between what is contemporary or ancient, sentient and non-human, alive or not. The way that Anahuacalli operates does not fit into those definitions, and instead portrays time as something continuous. In the end, I do not know if things from then or now are totally different. That is not the art historical viewpoint, or the default archeological explanation, that anything beyond our understanding was made for ritual purposes. Maybe the work was made because the person couldn’t help it—isn’t that enough of an observance of ritual, or even of faith? The desperate, ongoing urge to create, without expectation that anyone will ever speak back—to communicate with an unseen viewer.

KN: Your pieces have now also become artifacts in this “temple,” which is pre-activated in a way, since it was designed to appear much older than it is, and hold objects from different places and times within its structure.

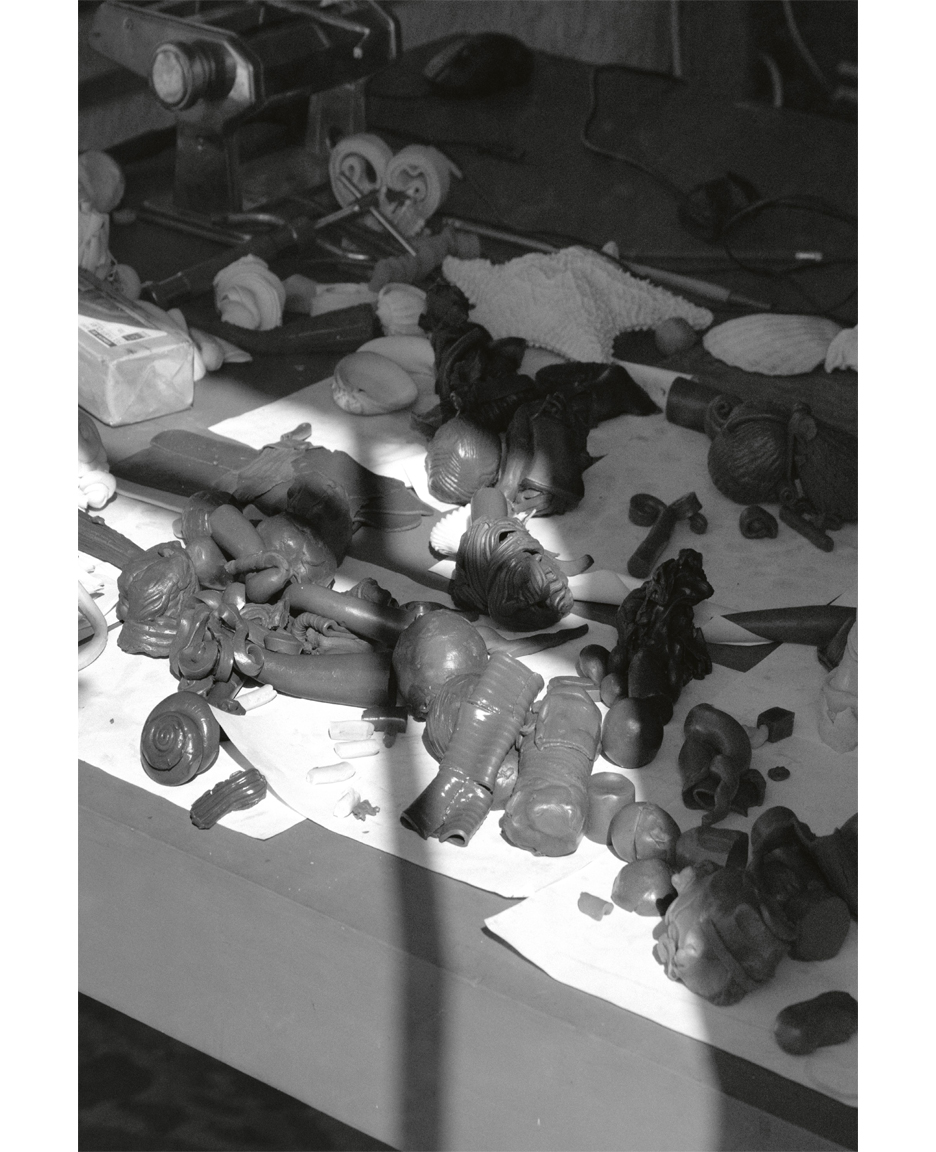

AA: Right—they interact with one another. In this sense we see a shared characteristic; that they are animated, they are alive. While the pieces I made are of bronze, they remain active. I did not approach the work in a formal way, but instead tried to make pieces that are in some way related to the collection in spirit—that attempted to speak to the same entities, or forces.

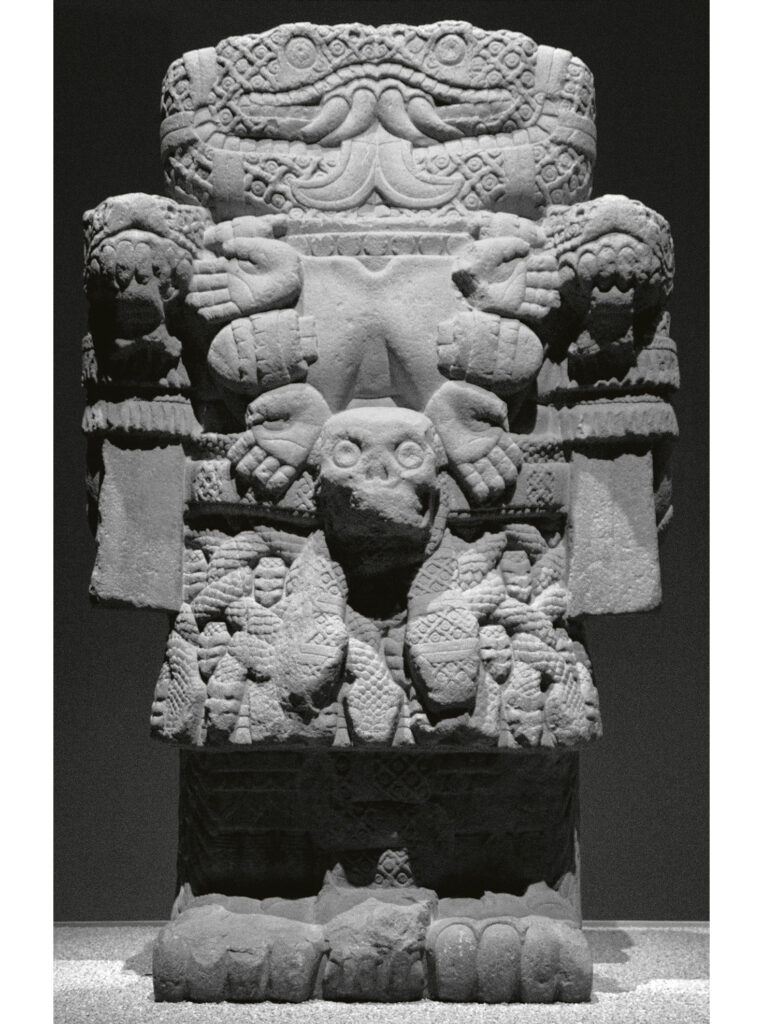

KN: For Rivera, what belonged to the soul of the object versus what belonged to its form had much more license in pre-Columbian Colima and Mesoamerican cultures—for example, the hybridization of the figure, of vessels composed with the body of a woman and snakes instead of feet, or the arms of a crustacean. Between the animal and human form, this kind of double is also reflected in the objects’ use as both functional and ritualistic. We now know from archeologists, researchers, and anthropologists that these Colima pieces were not only used in daily life, but also as portals to access other worlds, activated through psychotropic drugs in rituals throughout regions of Nayarit and Michoacán. I think this ingenuity you share with Rivera, who despite his privileges and public identity as an artist often reduced his title to that of a collector of these small figures, is portrayed in the twenty-six new sculptures you made for this exhibition, positioned both in and around the museum.

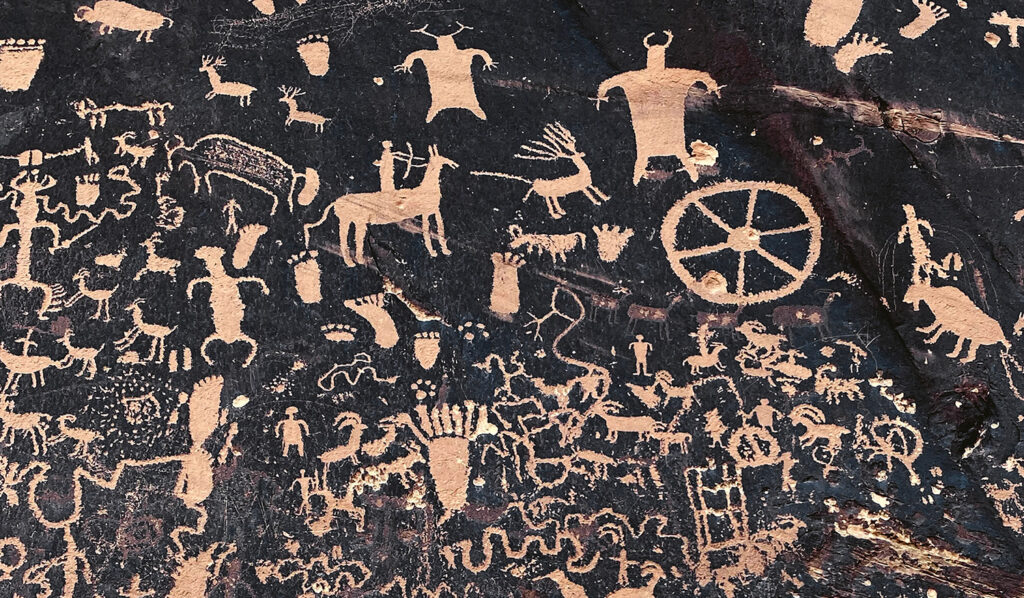

AA: I know one thing that my work shares is escape. I started making work when I was very young as a method of communication—I grew up in an extremely religious context and did not understand there was a world outside of that system of belief at the time. The only books in the house were religious texts. I had never gone into cities or had television. But as a child, I would go into caves and see petroglyphs [throughout Utah]. It was the only artwork I knew. I was convinced, at maybe seven or eight years old, that the people who drew these petroglyphs were still around. So, I would make objects for them, little carvings with my pocketknife, and leave them for the people that were making the markings. It was a desire to communicate, and I still feel what I am doing is meant to communicate in a pre-language kind of way—to catch a feeling or moment of transition.

When I make a piece, even now, I think it is going to help me communicate with the people who made the petroglyphs, with the people who made the Colima works, or with some other consciousness, within myself, or in the spirit of the world.

KN: Do you think that the objects you make contain some religious value?

AA: For me, sure, in a way. A lot of my work functions like little totems, like a totem for an experience, and then I put it away. I make a lot of variations; I go into a trance. I don’t make drawings or plans, and even if I have a plan in my mind, I almost never follow it. Each sculpture typically puts an end to this space, meaning the present, in order to make an experience of a physical thing, which becomes a part of its own timeline.

When I was young, I was homeless, I was in a lot of trouble. I had to put my work on the street to appeal to people to help me, basically. Yet if I hadn’t been so desperate, I would not have realized that there are other people out there who will not only see you, but also recognize the attempt—the real attempt—to make a spiritual object, something to imbue with power. I feel that impulse is what connects us to something that is, say, one thousand or five thousand years old.

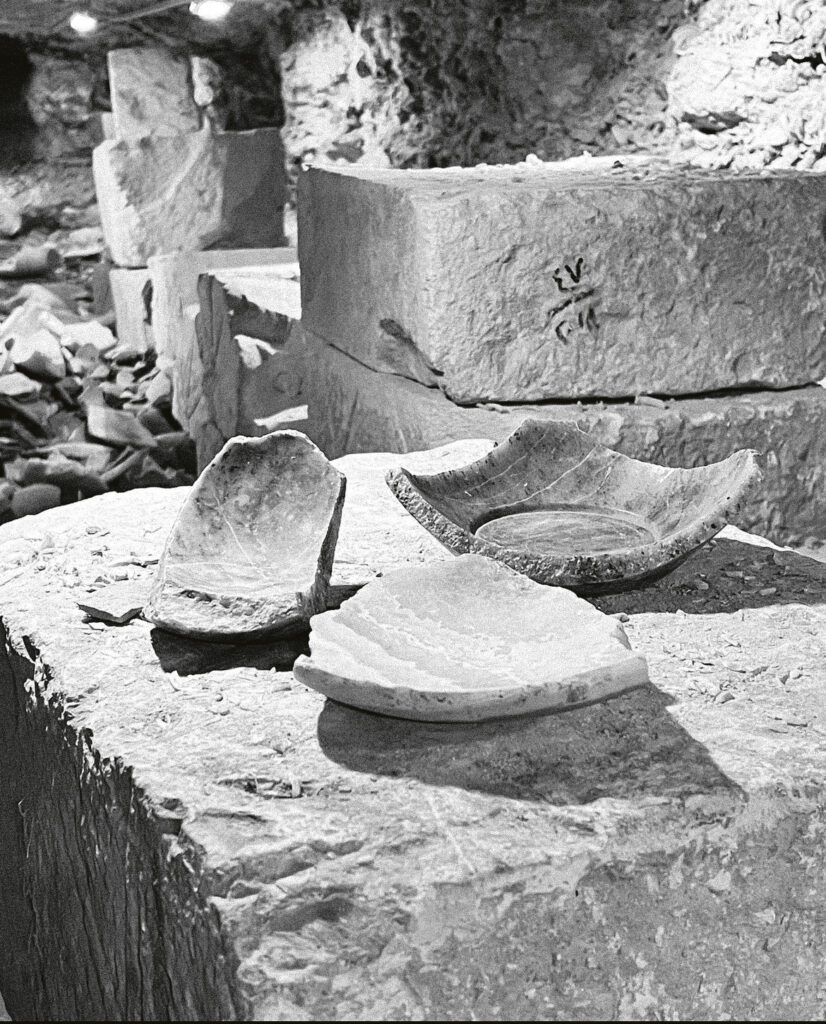

In Egypt, I went into a working archaeological site beneath the Pyramid of Djoser, considered by some to be the oldest pyramid, where they are excavating stone vessels that are at least five and a half thousand years old, they don’t really know. I was able to hold them, to feel how the people had worked them—both the sense of possibility and the love they had for this thing they were making, the movements. For sculptors, it is almost as if there is a separate religion and tribe of people. You see past, future, and present all at the same time.

KN: I think your works exist between realism and fantasy. I would not say in a surrealist manner necessarily, like Juan O’Gorman, but I think of José Maria Velasco, a Mexican painter who was well known for his landscapes of places that did not actually exist. In his depictions of volcanoes in particular, he knew so much of physics that he could make you believe they were done from life. The construction of Anahuacalli similarly extracts all these types of artistic and cultural experiences, which are now in the center of contemporary art discourse, that can be decoded from different perspectives from anthropology, archeology, design, and architecture. Although it looks like a pyramid, it is not a pyramid. While non-machine technology was used, different technologies which were developed in the 1940s and ’50s were used to raise the building, completed in just 1963.

AA: Right, and I am not so interested in technologies. I just use what is available in my lifetime for fabrication, but I still do it in the way people have done it forever, which is by hand.

KN: Perhaps one example is the use of artifacts to solve problems, or the analysis of artifacts to build an understanding. These are also forms of technology.

AA: Exactly. In Egypt, it was interesting because so many of the Ancient objects there are very formal—one specific form fashioned repeatedly. But then, there are little moments that are not, which is what makes them so incredible to me. In those instances, you glimpse the hand of the artist, and more than just the physical movements of the hand, but also their complications. And kind of excessively so in Colima pieces. They are very active and effusive.

KN: You are obsessed with the pieces from Colima in this collection.

AA: The ones that Rivera collected have immense energy, which does not exist in so many other cultures during that period. The art in Anahuacalli is often much more fluid, especially the pieces from what is now Western Mexico: Jalisco, Nayarit, Colima. The Olmec work is amazing too, especially after seeing the stiffness of Egypt—

KN: We do also have a stiffness in Aztec—

AA: But that is not so interesting to me, the grand formal classical art. The Olmec wrestler sculpture is dynamic; it is a masterpiece in posture, that they insist to call it a wrestler though he is not wrestling anyone, and not primitive in even the remotest way. To me, there is a misclassification of art objects based on where they were found, or in which time period, and not the skill or dynamism of the work. I think the Colima objects are some of the most remarkable things humans have made. They possess a total effortlessness, in the sense that the people who made them did not lack the skill to do whatever they wanted. They were completely in power and control when they were working. The humor, the lightness, the effort—I also try to get to that magic place where you are not so burdened by what you can and cannot do, but only limited by what you mean, which is what is so fascinating about seeing it all now. On a basic level, before ideology and religion are introduced, elements of these ancient objects are kind of similar. There is speaking. There are humans speaking.

KN: We have spoken about Juan O’Gorman’s influence on Anahuacalli following Rivera’s death and the concept of organic architecture. He was completing this museum almost therapeutically—perhaps in reaction to the catastrophes that were affecting society in the 1980s. He was somewhat crazed by the fragility of the world and universe, so he tried to create all these fantasies, while also acknowledging that it is a reality of our world. Are you trying to create, in some ways, similarly fantastic figures?

AA: We have a lot of similarities. I have always made animals, but they are totems in my work. I feel like I occupy O’Gorman’s vision of the world you just described more than regular public space because I spend most of my time working by myself, making objects, or spending time with my children. And I do not like to talk about the meanings behind my works, but I am working through experiences to isolate sensations within them, and let them go. I do not expect the work to solve a problem, as in self-helping my way through my artwork, but in the sculpture actually going away and having its own life. I still feel like I am trying to make a type of hieroglyph, a combination of things that pictorially portray a thought, understandable without language from associative characteristics.

One of the few things I find interesting is if I make a good shape, or if I do something that somebody else can find meaning in. My ideal experience is if someone sees something, not knowing either where it is from, when it was made, or who made it—having that connection totally severed.

KN: Essentially like Anahuacalli. How do you perceive time?

AA: Honestly, I am confused about time after being in Egypt. It is bizarre to hold something that is at least seven thousand years old, perhaps even twenty or a hundred thousand years old, that was made by a human being and is still perfect. We do not really know when they were made, since the site has not been fully studied yet. In an adjacent tunnel to the active archeological site I mentioned, there was a recently excavated calcite box, which is like a type of onyx. It looks like the same material as the windows here at Anahuacalli, but they hadn’t had any record of the mineral existing in Egypt until now.

KN: Tecali—the translucent stone?

AA: Yes, similar. The strange thing was that the looters never got to it, because they would have taken it. It was just this perfect multi-ton box—not for a person, not a sarcophagus—and there was no explanation of it. I did not take any photos at the guard’s request—they were letting me in at night into this place we were not supposed to be. So even now there is no record of it, but I have seen it on my hands and knees deep in this tunnel. There is nothing like it in any museum. I know it is there, and for the rest of my life I will never have an answer. Like, what the fuck was that box! Very weird.

With all my experience, all the technology I have, I would have had a hard time making that box. It was supposedly pre-Bronze Age, but this was not like the kind of thing you could make with a stone tool. I have looked at a lot of stones in my life—I do not have an answer, and I cannot go back. But that stone is there, among these new sculptures, like my work is here, out of time. Why is that?

KN: Because time is not linear, Alma. The answer.

AA: I have no idea what time is.

Kasmin Books is pleased to present Alma Allen: Nunca Solo, a catalogue accompanying the artist’s exhibition at Museo Anahuacalli, Diego Rivera’s iconic museum in Mexico City. With translations in both English and Spanish, this volume delves into Allen’s ongoing engagement with time, form, and hybridity through twenty-six newly commissioned sculptures installed among the volcanic architecture and grounds of the museum, available for pre-order here.