In celebration of the exhibition Bernar Venet: Gravity, The Kasmin Review publishes the first English translation of BERNAR VENET, THE HYPOTHESIS OF GRAVITY. Written by Maurice Fréchuret and translated by John O’Toole, the essay was first published in 2021 and unveils the radical conceptual and theoretical origins of the artist’s practice through his painting, sculpture and performances from the 1960s onwards.

Photo: Jean-Pierre Quarez

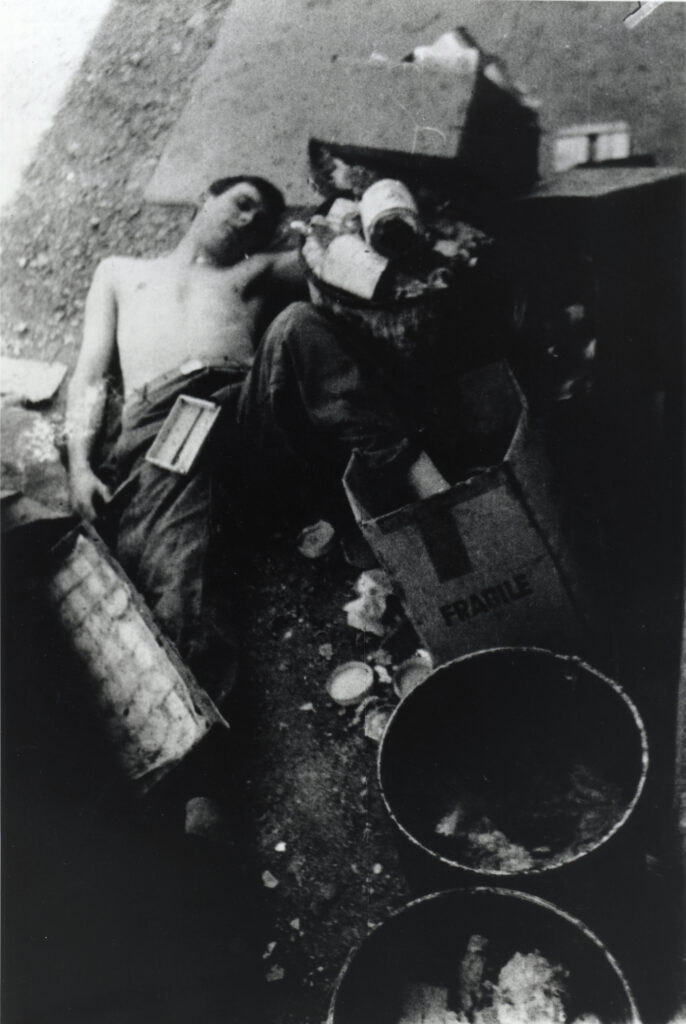

Lying on his back directly on the floor, bare-chested, one arm extended, the other stretched along his side, the left leg bent and resting on a support, the right prolonging the line of the arm, the head leaning on the shoulder, eyes shut. The man is laid out as closely as possible to a heap of objects in which can be seen open trash cans, crates, pieces of paper, cardboard lids, cans, and other rubbish that is harder to identify. The black-and-white photographs that have come down to us, shot from various angles, show a body dressed only in military fatigues on which is scattered the rubbish that had spilled over from the bins. One of the shots, taken vertically, provides a glimpse of a window with small panes and a crumbling, quite dirty wall. The ground is also in an awful state, made up of soiled slabs of cement and bare patches covered in broken bits of rock and gravel. The place is easily identifiable as the trash can area of a community that is not terribly fussy about standards of hygiene. The presence of the body is, however, the subject of much speculation. An individual who accidentally slipped, the fall of a man under the influence, a person who has just suffered a serious cardiovascular incident? Although there may well be a stronger argument for retaining the terms “fall” and “accident” afterwards in our study, they cannot adequately cover the present scene. The reality is more surprising. What can be seen in the photos is an artistic gesture carried out by Bernar Venet in the spring of 1961 quite close to the mess hall of the barracks in Tarascon where he was doing his military service. Documented thanks to the photographs shot by his army pal Jean-Pierre Quarez, this performance, as the artist himself has always insisted it was, stands as a primordial, even foundational moment in his journey.

Photo: Jean-Pierre Quarez

Its power lies in the fact that it resists the initial interpretations the pose, context, and site ought to inspire. At a moment of history that was so very fraught, which witnessed the referendum on Algerian self-determination approved by a quite solid majority of the people, the founding of the far-right French organization opposing an independent Algeria (the OAS), the putsch by French generals who were hostile to the new policy pursued by General de Gaulle, and the deadly breaking-up by the police of a protest march in Paris mounted by the nationalist Algerian movement the National Liberation Front (FLN), Venet’s gesture could easily be perceived as an antimilitarist reaction that the prospect of leaving for the Algerian interior rendered even sharper and harder hitting. Nothing of the sort. The artist has always maintained the opposite. “It wasn’t a symbolic gesture, even in those troubled times when the war was raging in Algeria – Algeria, where I was going to be sent several months later,” as he made clear in an interview with Catherine Millet.[11]

One might read the pose struck by the artist in such a neglected and rundown space as his way of publicly laying claim to the cynical themes of a Diogenes decrying social conventions and especially, in those early days of the jingly ballyhooing of the consumer era, the spectacular world of objects.[2] Such a hypothesis isn’t worth considering either, and Performance in Garbage affords not a whit really of proselytizing for the simple life removed from every consumer temptation.

If, however, the positioning of the body and limbs immediately excludes any kinship with the gisant, the recumbent statue, the funerary figure all stiffly straight and stringent, the fact that the head is resting on one shoulder – to the right or left according to the photograph – could add weight to the argument that this is a Christlike figure. Yet here, too, the association is risky and appears to be quite inapplicable in light of what the artist was to produce later on.

Actually, if none of these readings seems to win broad support, Venet’s action can only be situated in a history of forms and the developments associated with it. At the start of a period that promised to be especially innovative, art in its practice and definition was deeply questioned and fundamentally challenged. Some forty years after the Dadaist revolution, the question of art was forcefully raised once again, opening up a new field that would prove especially fertile. The 1960s and ’70s would indeed rethink the function of art entirely. For certain artists, it was the direction towards the flow of life that predominated; for others, it was a matter of questioning the very fundamentals of art. Movements like Fluxus, groups like Ecart and Untel, and individuals like André Cadere and Ian Wilson embodied the former option, raising the highly pertinent question of art in its relationship to existence while attempting to reduce as much as possible what had long and inexorably separated the two. On the other hand, movements like Minimalism in the United States, Supports/Surfaces in France, and Art and Language in England were to pose the question of art in its very essence and redefine its foundations in order to establish it as an activity in its own right. But, before all else – the essential indispensable exercise – there had to be a clearing away, an erasing of everything, and the establishment of a kind of zero degree from which it would be possible to rebuild. Negation at work but also negation with an eye to producing a work of art. That is, I think, the meaning of Performance in Garbage. Stretching out in rubbish and covering his body with some of it, Venet committed an indescribable gesture that not only broke with the usual art practices but also undermined the very image of the artist.[3] Reduced to the level of one object among many, he heightened Kurt Schwitters’ gesture of collecting scraps of paper, cloth, cardboard, and wood in order to recharacterize them as artworks. He went beyond Arman’s gesture, whose Trash Cans became works of art, too, all in the name of calling into question aesthetic principles and reevaluating artistic criteria. The action Venet staged in the spring of 1961 was part of a search for the ultimate and the unsurpassable that a few others during the same period, or earlier in the century, had also undertaken.[4] The limits of art that a Rodchenko wanted to attain through the purity of the three primary colors, or that Yves Klein passionately sought in the color blue and fire, Venet placed them in mud and filth, in scandalously disqualified materials.[5] Through a proximity that was not at all insignificant, the artist knew he was putting himself in danger while scuffing up the very positive image that adhered to the status of the artist. Still, the experiment had to be tried, as he himself made clear: “to see just how far it was possible to push back the limits of the artist’s behavior.” Here then was the declared objective that Bernar Venet proposed reaching through this memorable exercise.[6]

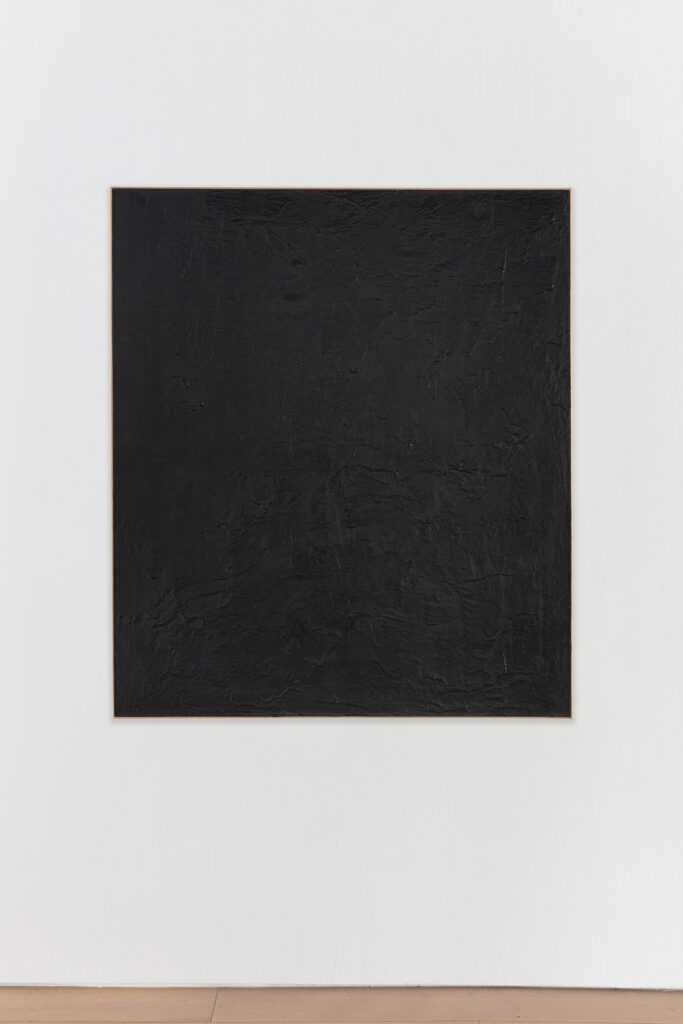

Tar on canvas

149 x 130 cm

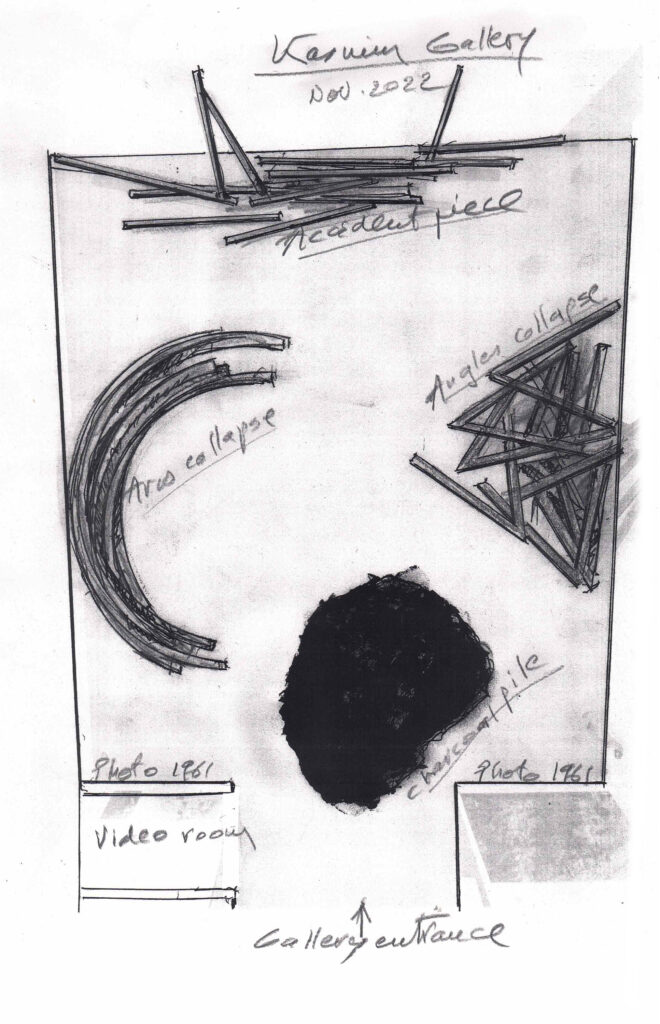

Bernar Venet: Gravity, Kasmin, New York,

November 4–December 23, 2022

Photo: Diego Flores

Through its radicalness, the gesture he invented seems indeed to break with an evolutionary and progressive history of art, and appears to mark a kind of point of no return. In fact, the burden of negativity borne by his act is so strong and absolute that it seems it can find but one outcome, one way out, its conversion to something positive and upright. Once the zero degree has been reached, the tabula rasa achieved, it is actually possible to set off again and find a new impetus. Flat-out on the ground and simply flat, Venet’s performance lies at the juncture of two attitudes, two trends, two ways of thinking and practicing art. It even looks ahead, in its way, to the resolution of the two poles on which that fertile decade was to construct its entire aesthetic. The trash cans of history are overflowing with the reactionary precepts artists have rejected, overflowing as well with outmoded programs and functions dating from another age. Fluxus and the BMPT group played an energetic part in wiping the slate clean and stated unambiguously their refusal to pursue the project. Their manifestos announce loud and clear their desire to go beyond the limits and free themselves from every norm. For that, everything had to be rethought, spread out and examined from all sides. This was literally what Venet did by sprawling on the ground. As incongruous as it was, his presence in that filthy run-down space marks a decisive moment, the moment of a possible renewal or, to extend the Christic metaphor, of an eventual redemption. We are, however, a far cry from the position of a Beuys plunging into the polluted waters of the Zuiderzee to ecological and therapeutic ends; a far cry, too, from the preservational happenings spectacularly staged by the Japanese artists working together under the collective name Hi-Red Center (Haireddo Sentā), scrubbing the pavement and sidewalks of the Ginza district in the center of Tokyo during the 1964 Olympic Games.[7] It’s not a makeover of the environment that Venet’s action was aiming for, but rather a renewal – devoid of prophesy and pomposity – of art practices that had been weakened by being mercilessly called into question over and over again. In Performance in Garbage, what was identified with vulgar, irretrievable decay would eventually prove, despite every indication to the contrary, to be an exceptional moment in which everything could be replayed, the formless could assume form again, and collapse and submission to gravity became a positive force, teeming with interesting possibilities and sources of new arrangements.

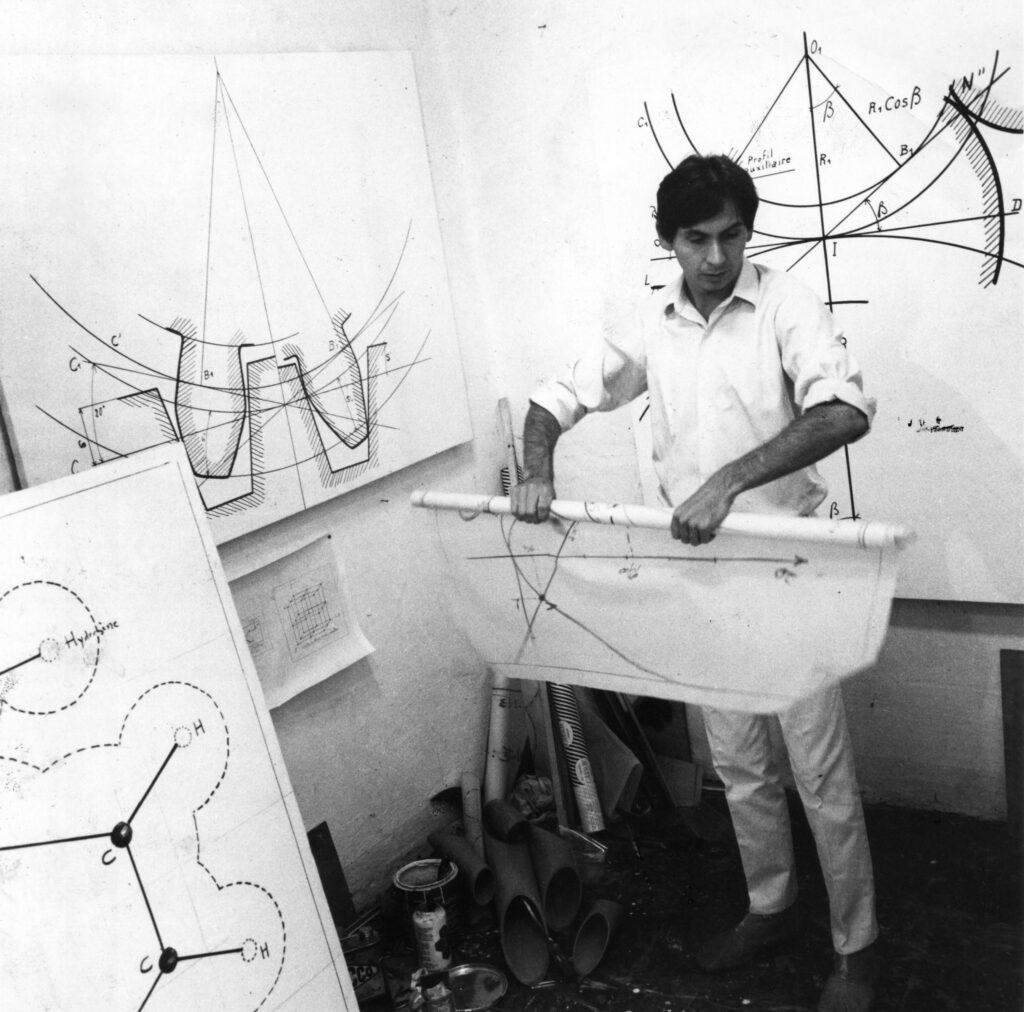

Avenue Albert 1er, Nice, France, 1963

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Sometime before Venet did his performance, the countryside near his military base in Carpiagne had been the scene of a phenomenon that had caught the artist’s eye. A large tar spill had oozed down the wall of a ravine, leaving a very obvious blackish slick over thirty feet high and nine to twelve feet wide. The artist’s interest in this spectacle was due especially to the very materialness of the asphalt, its color, density, and shine. But it was also the result of its physical characteristics, its viscosity, malleability, softness, ability to spread and to be stretched by the force of gravity. Fascinated by that spill and as if to show his keen interest in it, the artist had himself photographed striking a pose in which he is pointedly gazing at the black slick.[8] Strictly speaking, the shot doesn’t enjoy the status of an act of reappropriation, which was so commonly practiced by the New Realists and Ben (Ben Vautier; the French artist goes by his first name alone), but it is the concrete sign of his support for a gesture whose importance he already feels in his bones. Like the Performance in Garbage though, the tar spread over the hillside was indeed the outcome of a deliberate gesture, an act, a bit of physical labor voluntarily carried out. In both cases, action verbs have to be employed to characterize the process, i.e., spread, toss, pour out, throw, hurl… That is, all verbs expressing will and determination, which end up achieving contrary states through an odd inversion. Like tar, the body accepts being subjected to a law, that of gravity, which has become intangible to it. It accepts being dominated by a force that reduces it to the state of an inert thing, strewn on the ground, like the objects surrounding it. The verbs themselves seem to have lost their arrogance and sunk into passivity. To topple, fall, slip, these are synonyms of fragility, even weakness. The history of art is full of figures who are falling or collapsing. Alberto Giacometti, Germaine Richier, and Tal Coat dealt with the theme of the fall and falling in order to express the difficulties associated with existence itself or with practicing the profession of artist, which came down to the same thing for those three. Before them, reviving the legendary figure of Icarus, Caravaggio offers us a masterful version of it in his Conversion of Saint Paul. Rodin created another, also exemplary, for the Gates of Hell and thus confirmed the image of a curse that attaches to it.

Venet – paradoxically – attributes a deliberately positive value to it. Here lies his achievement. The artist’s choice, wholly and consciously embraced, plays a part in the significant transformation of this pose by lending it a radically new meaning. Body, tar, coal, and later steel bars were to materialize in succession the fall, not simply to represent it but, more precisely, to integrate it as an element that is intrinsic in the work of art, source and result at one and the same time. It was not to symbolize some lived malaise or express some existential difficulty, but rather to point up the beneficial power of gravity, the energy it contains, which we are free to take advantage of. Venet inverts the usual symbolism of the catamorphic schema. He breaks with the image of regression linked with it just as he breaks with the image of gloom that is also associated with it. While the French verb sombrer (to sink) reveals two etymological lines of descent, i.e., chuter, to fall, and assombrir, to darken, fill with gloom; the fall, that is the submission to gravity, in Venet’s work, was to prove, as Arnauld Pierre observes, “particularly operative when the need to spawn a literal and anti-subjective art was to grow even more pressing.”[9] It was no longer synonymous with failure or catastrophic ordeal. It did not bear the fatal hallmark of vertiginous death, as with Icarus or Phaethon, but rather was full of possibilities and open to a promising future.[10]

The artist installing Pile of Coal for his exhibition Travaux 1961-1979, Institut de Villeurbanne, France, March 14–May 31, 1997

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Bernar Venet: Retrospective 2019–1959, Musée d’Art Contemporain (MAC), Lyon, France,

September 21, 2018–January 6, 2019

Photo: Blaise Adilon. Courtesy MAC Lyon

The artist’s fallen body and the asphalt spread over the steep side of the hill indicate the same direction, the ground, the earth, a lower place. The ground is not at all some eventual and final convergence; it becomes the new scene where novel art experiments are born. Bernar Venet was to choose it for his own artistic discovery and for the long term, making it a space where painting and sculpture obey unusual rules. The tarred paper and cardboard works he did in the same year, 1961, attest to that. Having got for himself a supply of asphalt from the Highways Department, the artist heaped it on sheets of paper laid out on the ground and, standing above it, spread it with his feet over a large part of the surface.[11] The example of Kazuo Shiraga may have popped up in his memory. The image of the Japanese artist moving around in clay spread over the ground, kneading the material with his feet, legs, torso, his whole body, remains a point of reference that Venet readily acknowledges: “The first works of that period are either pours, or gestural paintings a bit like the Japanese artist… In a performance from 1955, Struggle with Clay, Shiraga struggled nearly naked with a pile of clay until the trace of his movements in the clay became the real artwork.”[12] Obviously, Venet’s initial attempts deserve to be compared with what Shiraga had done several years before him. The half-nakedness, the soft material used by both, the bodily poses, the acceptance of randomness are features common to the two approaches. But what links them even more is that ground where they move about, that old preposition rez in French that is mostly forgotten and no longer in use except in combination with several nouns (rez-de-chaussée, for ground floor in French, and rez-de-jardin, for garden level). Yet rez expresses immediate proximity with things, their osmotic relationship. It is no accident if both artists advanced in this way, working as they were at the time with a thick and dense material at the very limits of viscosity. Adherence was all the stronger, and the initial project more adequately followed up. Using the ground as a support was, in this instance, to be on the (same) level with the work of art, without the distance imposed by the piece hanging on the wall or resting on the easel. Being directly over the surface one is working is to be but one with the piece, especially when the feet get to work and replace brushes. Others before Venet had experimented with this “getting things straight,” “clearing things up,” by spreading things out on the ground at your feet. There was Pollock, of course, who certainly did not shrink from unrolling his canvas on the floor of his studio in Springs, New York, in order to cover it, in a fierce dance, with the colorful tracery that dripping and pouring practices made possible. The American artist explained this choice, speaking of his need for a hard surface on which to pose the canvas, free and unframed, and from whose sides he could more easily reach it, singing the praises then of a process that allowed him to be “literally in the painting.” It remains a historic example, remarkably captured by Hans Namuth in a series of photographs and eventually a film whose international popularity did much to earn Pollock’s work its recognition, but before him other artists had used the ground as the direct support for their experiments.

Coal

Sculpture without a specific shape

Bernar Venet: Gravity, Kasmin, New York,

November 4–December 23, 2022

Photo: Diego Flores

Despite his limited sources of information, in the early 1960s Venet looked into what the century had produced and what other artists had proposed. He didn’t disregard the work of those who came before his own attempts. They were for him formidable examples of openings, not necessarily to follow faithfully but rather to reappropriate in order to better extend them. This is how he came to recognize the importance of Marcel Duchamp’s contribution, more specifically that of his 3 Standard Stoppages (1913), clearly grasping the effect of Earth’s attraction on those wool threads, which is what constitutes the work of art. Thanks to Duchamp’s piece he understood the measure of chance that had since come into play in making art and to which he now laid claim, convinced his approach was the right one and aware of the consequences of his work. There are other examples he wasn’t necessarily familiar with at the time but they would also eventually reinforce his take on art. The example of Jean Arp, who tore up a sheet of paper and let gravity scatter the pieces over the ground, as Duchamp had done with his wool threads. And that of André Masson especially. The works that to me ought to be the most closely associated with Venet’s here are the Surrealist artist’s sand paintings. In the fall of 1926 while staying in Sanary, Masson began a new series of paintings which he wanted to do with the same spontaneity of his earlier automatic drawings and their random line traced out on the sheet of paper. Naturally the techniques varied considerably and Masson only achieved his aims by inventing a new one. This involved spreading glue on the fly, as it were, over the canvas lying on the floor, covering it with more or less finely grained sand, righting the canvas so that the areas of sand left unglued fell to the floor, and finally, as the case may be, reconfiguring the whole by painting human and/or animal figures suggested by the shapes that had appeared. The initial phases of Masson process are precisely the same employed by Venet in his Tar paintings, except for this one point, that it was neither glue nor oil paint but the well-known material gracing so many roads and highways under foot and wheel: “I’d pour the tar directly on the canvas laid out on the floor and, with a squeegee, spread it evenly over the whole surface. I’d then lift the canvas up to position it vertically and cause runs, which formed because of irregularities in the layer of tar. I’d turn the painting several times and set it on each of its sides until the tar began to harden.”[13]

The paintings by each of these artists share only the gesture that produced them. They are fundamentally different due to the spirit haunting each output. The clearly embraced spontaneity of the Surrealist artist is no longer the experimental vein explored by Venet, who was beginning to distance himself from it around this time, when the expressive gesture characterized a large part of artmaking and had become the most common way of producing works of art. True, among Venet’s earliest works, Production of Five Drawings in India Ink in Three Seconds (1961) can seem like the artist’s adhering to the principles of automatic writing, whose dazzling speed and immediacy were meant to capture the strong emotions affecting the author. The process Venet followed contradicted, it seems, the hypothesis in question. Indeed, the five sheets of paper laid out on the floor initially formed a continuous strip over which, in the short lapse of time he had set for himself, the artist poured the ink directly from the bottle he was holding at arm’s length. However, the five sheets only remained side by side for the time it took to produce the work of art, such that the initial gesture was arranged in a sequence and lost its demonstrative value of spontaneity. The irregular line slashing all the sheets together and the splashes resulting from the drip technique were nothing more than traces of the gesture, a recollection of an act and not a work of art in its own right. Only ever displayed on the floor along with the inkpot that was needed to produce the piece, the five sheets of paper didn’t actually form a polyptych meant to hang on the wall.[14] They were the outcome of an action the artist likes to reproduce at certain events and which he has always documented with photos shot during the performance.

Photo: Philippe Bompuis

The technique of working on the floor was to prove a great success and numerous artists were soon using it. As we’ve just seen with Venet and his early work, the technique lent itself remarkably well to experiments in recording gestures. Klein’s dynamic anthropometries (1960), those that led to the imprinting of bodies in movement, were done on a support laid out on the floor. The same goes for Nam June Paik’s famous performance Zen for Head, which the artist did in 1962 during the Fluxus Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik in Wiesbaden. During the performance, the South Korean artist dragged himself backwards over a roll of white paper spread out on the floor, using his own head dipped in a mixture of ink and tomato juice as a large brush.[15] It was also on the floor that Shigeco Kubota drew a line with a brush she had clamped between her thighs (Vagina Painting, 1965).[16] As varied as these experiments and the motivations of the artists who carried them out were, one point connects them all, namely the decision to use the floor and horizontality. As founding elements in new practices, they introduced a novel relationship to the work of art by bestowing greater range on the body and gesture. Production of Five Drawings in India Ink in Three Seconds and the tar works are perhaps, as Thierry Kuntzel suggests, an attempt to break free of gestural painting, a way to reorient art in directions in which the artist’s expressiveness was to be less effective.[17] Still, the title given to this piece clearly indicates the importance of the gesture and the primacy of making and doing. Not Five Drawings… but the Réalisation de cinq dessins, the Production of Five Drawings… To have done with gesture, to get over it, sure, but if so, then in excess, brilliance, and off-handed elegance. The artwork in question was to be the inverted introit, the reversed introduction to a new period, one in which the concept and developments of pure abstraction were to dominate. Venet once asserted to Eddy Devolder that a new method should bring about the ruin of the earlier method. In agreement with Devolder, Venet seems, in this act, to have put an end to the gesture as artistic expression and therefore pointed his work in new directions.[18] Towards rationality and monosemy, the objective language of mathematics, cold diagrams and neutral parabolas subjected to a denotational reading only. The drawing of a tube cut to form a bevel edge which he sent to Claude Viallat for the 1966 show ImpactI mounted at the Museum of Modern Art in Céret was of a piece with the new direction the artist intended to give his work, a direction we might characterize as conceptual if the term didn’t refer solely to the work of American artists.[19] The parabolic development of this or that equation (y=x²/4 or y = 2x2 + 3x – 2…) which he faithfully transcribed on the canvas is similarly a challenge thrown down before the interpretative temptation, which gesture and act could still summon. Other works like The Straight Line Represents the Function y = 2x + 1 from 1966, which is held in the collection of the Museum of Grenoble, or Gears with Circle Involutes, also dating from 1966, are part of the same demonstration.[20] Venet’s approach embracing radical objectivity achieves an industrial-like drawing here; the style should be likened, as the artist himself admits, to the experiments done by the pioneers of Constructivist art, in particular Alexander Rodchenko and El Lissitzky, whose work also integrated principles of scientific rationality.[21] Moreover, the artist would later pay homage to Rodchenko in 1977. Venet proposed two immense lines – a straight line and a curve – to be drawn on a wall of PS1 in New York. The piece was to remain merely a proposal until rather recently, when it was done for the show mounted at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Nice in 2018-2019.[22] The direct and unadorned use of scientific data would deeply influence Venet’s work for over ten years. Mathematical diagrams but also diagrams of water vapor (triatomic), phenol, or acetylene (C2H2), borrowed from science books and reproduced as such, likewise figure in this cold austere iconography that holds viewers at arm’s length and forbids any fictional development. Similarly, the plotting of astrophysical phenomena (Magnetic Storms) and electromagnetic radiation, and maps of spheroidal galaxies (Distribution of Variable Stars in Ursa Minor Dwarf System) were copied out exactly as shown in illustrations by the artist, who has always been careful to shatter any attempt at an imaginary approach, any fantastical reading. Venet also turned to tables from the securities market on the American stock market. The flows of capital through Wall Street were the subject of a precise report; the artist was happy to simply enlarge it. Pushing his demonstration further, however, and borrowing a language that everyone could grasp, Venet duplicated weather graphics directly from newspapers (Weather Reports, 1967-1969). The photographic enlargements of these plates are dated the same day they were published and, like the originals, feature maps of Western Europe with their areas of rain and snow, the isobars connecting the same mean air pressure measured in millibars and other technical observations. To clearly show that what we are seeing is simply graphics taken from French and American newspapers, the artist has left bits of the articles that ran to the left and right of the printed box. As summaries of scientific observations and measurements, these artworks speak of the heavens and the earth but in an idiom that turns its back on all literary or metaphorical interpretations. Even the stars, a subject that is especially favorable to poetic developments, are subjected to an extreme reification and become a series of points distributed throughout a space that is strictly ordered. The photographic enlargement of such representations remains perfectly faithful to the original layout and displays the same objective neutrality. The heart, the very image of human feelings, is no more than an organ whose beats are recorded (Cardiac Auscultation). The LP that Venet cut in 1969 recorded the heartbeats, the normal rhythms of the heart but also the changes that may appear, the murmurs and other pericardial friction. [23] It is the sound equivalent of charts and diagrams, quantifiable readings and mechanical schemata. With this the artist pursues his long quest for a reality that he would like to be resistant to any personal or subjective hold on it.

Laminated steel

Site-specific dimensions

Galerie Karsten Greve, Paris, 1996

Photo: Courtesy Galerie Karsten Greve

Although governed by the postulate of objective demonstration and mathematical rigor, Venet’s work would not relinquish the elements produced by the inflection of the body and the dynamic connected with it. The physical gesture then, associated with the force of gravity, was to remain a foundational element in many of the artist’s later pieces and would lend perspective to the objectifying scope of his undertaking. The law of gravity would continue to be that “hand” which Thomas McEvilley speaks of, becoming a central element in many of the artist’s experiments.

Pile of Coal is the most symptomatic example in this regard. Thought up and produced in 1963, this major piece in Venet’s body of work admits the double principle of the gestural and gravity. As with the tar spill of Carpiagne that so captured his attention, the artist was stopped in his tracks by a heap of gravel and tar that came from roadwork near Nice’s Promenade des Anglais. The elementary form of this volume of mixed materials drew his eye just as, at roughly the same time, another pile made up of gravel was being observed by Ben.[24] While the form-heap interested both artists in Nice, their approaches were fundamentally different. Ben’s approach comes in the wake of the Duchampian readymade. The pile was already formed. The artist, tapping into his own status, sets the artistic value of the object, thus lending it a new identity independently of what it truly represents. Venet’s approach is more constructive in that he himself created the pile.[25] There lies an interesting paradox that deserves our attention. Ben, the artist of multiple and varied gestures, bodily poses and physical acts, recorded and meticulously documented as decisive life moments, views a pile found on the road and, in a purely conceptual step, seizes it and raises its status to a work of art.[26] On the other hand, Venet, whose work would soon obey the strict rules of conceptual art, was sufficiently touched by the view of a heap of gravel that he undertook to erect one himself. Erect? The term is incorrect because what interests Venet isn’t the pre-established construction of a form, the fashioning of a volume, but rather the free progression of matter in space. What the artist wants to highlight isn’t some artistic feat or the virtuosity of the sculptural gesture, but the ability of the material – coal – to find a form as soon as it is subjected to the force of gravity alone. One might object that Venet was physically involved in producing the piece – certain photos attest to that, showing the artist spreading the material, shovel in hand – but the physical investment was only circumstantial and soon enough it was quickly delegated to the technical staff of museums and other exhibition venues. What predominates in Pile of Coal then is more the idea of the pile, the pile that takes shape, the pile that constructs itself, than its formal specificities or the gesture – however real and powerful – that engendered them.[27] In this particular case, there is no clear demarcation between the real and the conceptual. The idea and the project do not eliminate the gesture that constitutes the work of art but does put in perspective the artistic scope of that gesture while re-evaluating the properties of the material and its “support,” the law of gravity. It is worth noting here that the figure of the pile as archetype of the most elementary and immediate construction interested many artists of that generation. As we have seen, Ben’s piece of art is roughly contemporary with Venet’s, which would be followed by many other experiments I’ve already had the chance to study, over twenty-five years ago now, in a book that indeed boasts a chapter called “Entasser” (Piling Up).[28]

Photo: Courtesy the artist

I pointed out, for instance, the similarity in the gestures of Janis Kounellis and Bernar Venet, but emphasized above all what distinguished them fundamentally. The piled-up coal of the former essentially counts thanks to the energy force of the material and the imaginary charge it conveys. It is above all the fossilization of the vegetal, the result of a slow decay under pressure, nature and the transformation of nature at one and the same time. In Venet’s artwork, the tons of anthracite accumulated on a relatively limited space delivers no symbolic message, no reference to an unknown time causing matter to settle, to sediment, no allusion to the bowels of a concentrated earth brought to light by great terrestrial upheavals. Displayed inside and less frequently outside, Pile of Coal is primarily, not to say exclusively an aggregate of matter, the only property of which the artist chooses to highlight is that of accepting being spread out or around, that is, responding to the entreaties of a force that draws it downward and through which it takes shape, assumes a form. Venet’s work is indifferent to what in other art pieces immediately finds expression. I’m thinking of Hill of Sand (1962) by Michio Yoshihara, a founding member of Gutai who materially transcribed the objective set out by the Japanese art association in a manifesto: “Gutai Art does not alter matter. Gutai Art imparts life to matter. Gutai Art does not distort matter. / In Gutai Art, the human spirit and matter shake hands with each other while keeping their distance.”[29] But I’m also thinking of Giuseppe Penone’s Patate (1977), that heap of potatoes that reveals here and there parts of the artist’s face which were copied in bronze from a cast made of it. As before, the vital themes are abundantly present in this piece. An original example of self-portraiture, Penone’s work offers up a narrative, that of his very own person, story, being even. The piece gives us an accounting and an account. Which is not at all the case in Venet’s mound of coal. His work offers no account, no story, unless it is its own physical playing out which no connotation or mythical or emotional resonance sidetracks from its own trajectory. The monosemic position it adopts forbids any notification other than the one that informs us about the gesture that gives rise to the piece, records its progress, and registers its final state.[30] The limits the artist sets himself as a “maker” of artworks by leaving it up to the piece to self-form, build itself, or (if the word doesn’t run too much against reality), to raise itself, do not alter his creative abilities in the least. He simply chooses, not to direct the material or master it, but rather to delegate his expertise to it and bring it round to fully accepting its propensity to form a pile. As the zero degree of sculpture, Venet’s pile of coal turns away from all forms of allegory and metaphorical implementation. Even childhood memories, so persistent when the art involves plays of construction or grinding down of the material, give way to the work produced by the artist, who is completely mobilized by his demonstration. The nuggets of coal that he allows to take over the field refer to their naked materiality, which is foreign to any and all narrative or biographical amplification. They contain nothing of what constitutes Joseph Beuys’s piles of fat, nothing of the therapeutic value of that material gathered on the seat of a chair or heaped up in the corners of the venue, nothing of its redemptive power. Venet’s piece is more aptly compared with works by American artists like Robert Morris, Barry Le Va, and Richard Serra. The same determination to leave gravity the possibility of forming or deforming materials lies at the roots of their experiments. Morris’s best-known works are those made of felt offcuts which the artist hung on the wall to allow the form to construct itself. But along with those, the American artist generated others fashioned from the same pliable and relatively easy to handle material, which he heaped up on the floor or pushed against the wall, producing felt piles. Untitled (Tangle) from 1969-1970 and Untitled (Pink Felt) from 1970 are fine examples of this way of working (or not working) that radically changed our view of sculpture. A few years after Venet’s Pile of Coal, Barry Le Va’s spectacular accumulations of earth admit the same principles of this laissez-faire. Strewn over the floor, pieces of felt are scattered here and there, forming small mounds in no clear and precise order. A few glass plates, when not broken, organize this fractured and fragmented landscape, referencing in the strict rectangle of their surface the chaotic image of the installation. Continuous and Related Activities; Discontinued by the Act of Dropping (1967) is the title of the piece described above and it is part of the collection of the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York. The title-statement is indeed a fine summary of the act that was carried out and the gesture that accompanied it, a gesture whose discontinuity jeopardizes the expected organization of the sculptural whole.

Coal

Sculpture without a specific shape

Bernar Venet: Gravity, Kasmin, New York,

November 4–December 23, 2022

Photo: Diego Flores

Process artists according to the terminology generally adopted, Barry Le Va, Robert Morris, and Richard Serra were the figures in America who were best able to renew the practice of sculpture. Yet the work of European artists also helped considerably to effect these changes. The Briton Barry Flanagan, the Italian Michelangelo Pistoletto, the German Reiner Ruthenbeck, the Frenchmen Claude Viallat and Bernard Pagès, each in their own way brought new elements that likewise contributed in no small part to modifying and enriching the vocabulary of sculpture.[31] It is important to note that all of them, at some point, turned to the form of the pile, as if it constituted a decisive step in the development of these artists. Decisive and even primordial, if we take the oldest sense of the word and the original grounding which it refers to. By choosing this figure as early as 1963, Bernar Venet anticipated many later works and played a significant part as well in renewing the practice.[32]

100 tonnes, 2006

Laminated steel

Site-specific dimensions

Le Muy, France

Photo: Serge Demailly

As we have just seen then, there are two parameters characterizing the first part of Venet’s body of work, the material being used subjected to the law of gravity, and the initial form of the resulting pile. A third in the logical wake of the first two would soon specify a large part of his output, i.e., the collapse. To be more precise in my analysis, and in order to better define the artist’s growing production, I have to turn to this verb, but in a transitive sense. Not in the sense of a thing that collapses, but rather the idea of collapsing something, making it come crashing down. Use of the verb in a transitive sense is indeed rather rare. Yet it appears to be the one most apt to correctly convey Bernar Venet’s approach. To collapse is an action verb and it’s for that very reason that we need to use it. It fully reproduces the force of the gesture and well reflects the energy produced. The artist was to use the word as a noun and title some of his works Collapse. The term is adequate and formsa good gauge even if it tells us only indirectly about the supposed action and gesture. Between 2009 and 2012, Venet did about twenty works with that title. But other pieces dating from well before this herald the series in question because they are the outcome of the same experimentation. This is the case of the 1996 Accident. This piece involved some thirty straight flat-rolled steel bars – his Lines – that varied in height but had the same cross-section; they were posed vertically against the wall and separated from each other by a few dozen inches at most. The whole group formed a kind of metal curtain that stretched along the wall for some thirty feet. A single gesture would compromise the installation. Steady and decisive, the shove the artist gave the first of the bars located on the left of course caused all the others in the row to come crashing down and, in doing so, deconstructed the group. The film Thierry Spitzer shot of the collapse clearly shows the domino effect produced by this mere pressure on the one bar. Once the process is begun, the metal beams fall one after the other, making a deafening sound and forming in the end a huge tangle that can easily be identified with the pile.[33] Unpredictability was at work and only a few traces on the wall where the bars were leaning and which they scratched when they began to fall offer hints as to their movements. The first demonstration dates from 1996. It took place in Le Muy, where the artist’s studio is located.[34] For the creation of this piece, it’s easy to see that the usual parameters were activated, i.e., taking into consideration and using gravity, chance and indeterminacy; emphasizing the process alone; and aiming for the formal self-determination of the material. To these I could add the other considerations that are also dear to Venet, including refusing all symbolic and allegorical connotation; rejecting any historical reading that might expose the piece to the dangers of a possible illustration of a symptomology; and forthrightly laying claim to total objectivity that has its source in mathematical data. The accidental (random) combinations of bars on the floor can indeed be compared with the combinations chaos theory that had been identified and studied two decades earlier.[35] Even if the work of Henri Poincaré had opened up some very important fields of study, it was only in the 1970s that chaos theory began to be more fully laid out.[36] Venet likes to repeat that order and disorder, the chaotic and the unpredictable are elements that can create new directions for his sculpture and enrich it. He has made the connection himself between the science of mathematics and his work.[37] Already in the 1960s and 1970s, the artist had announced his interest in mathematics and made canvas paintings of equations, curves, and diagrams for their objective intransitive value alone. Equations were displayed in their original form, sometimes without even the formal translation they were given by the Constructivist artists, who were fascinated by the beauty in the curve, the ellipse, and the arc. Alexander Rodchenko, the Stenberg brothers, Nikolai Ladovsky, and Konstantin Medunetsky were, within INKhUK, or the Institute of Artistic Culture, the upholders of this art informed by mathematics and physics.

Site-specific dimensions

Corten steel

Le Muy, France

Photo: Jerome Cavaliere

Performed on July 17, 2021

Site-specific dimensions

Corten steel

Le Muy, France

Photos: Jerome Cavaliere

The works they created displayed all these right-angled, oblique and curved shapes, the impeccable definitions of which spring indeed from scientific data whose criteria of rationality and objectivity they claimed as their own in the name of revolutionary progress. The option Venet decided on is something else altogether. For him, borrowing from mathematics, its models and working drawings corresponds solely to the quest for an autonomy of art. The art historian Filiberto Menna was one of the first to reveal the monosemic direction of Venet’s body of work and point out that the artist’s use of the coded language of mathematics contrasted with “any stratification of meaning” and turned completely away from polysemy and connotation to attain the level of denotation only.[38] The Equation Paintings of the early 2000s, like those of the 1960s, provide no indication other than what they show. One of the remarkable examples from this initial period is the 1966 painting titled Graphic Representation of the Function y = –x²/4, which is held in the collection of the Musée National d’Art Moderne of Paris. The graphic projection of the function in question forms a parabola rising on both sides of a vertical axis that symmetrically divides the entire depiction. All is visible and readable on the picture. Thus, the equation of the parabola is written out beneath the graph. The grid pattern of the background looks like it’s the result of the painting technique of squaring but is more probably the grid on the sheets of graph paper used for drawing these kinds of graphs. The work is in fact an enlargement of a page from a mathematics manual that the artist faithfully transferred to a canvas. Venet has often repeated data of this kind and has occasionally even integrated an original element in the work of art. This is the case of a piece from 1970 that is held in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in Saint-Étienne titled Graph Theory and made up of two photo reproductions mounted on chipboard panels. The book from which the two copied pages come – the title page and table of contents – is posed on a pedestal beside them. That is, the work and the representation of a blown-up detail, the real object and its image. The dual relationship that we are shown here retains the memory of works in the past which managed to mix the truth and its image. Picasso’s Still Life with Chair Caning (1912), most of the Spanish expatriate’s Cubist collages, those of Georges Braque, Gino Severini, and Juan Gris, and Marcel Duchamp’s assisted readymades form a breeding ground for works by artists who were determined to insist on the primacy of the idea and prize concept over making. In paintings like Graph Theory, The Logic of Decision and Action, The Mathematical Sciences, and others of this period, Venet’s experiments echo the works of many other conceptual artists. The work of Joseph Kosuth, for instance, whose installations likewise articulate the real object and its photographic and textual occurrences, but also many examples by the group Art and Language, John Baldessari, and Stanley Brouwn.[39] These artworks lie, as the artist himself puts it, outside the purely formal field, so the matter of priority involves the artistic project itself.[40] Venet was to push this commitment to conceptualization quite far. Witness the piece he proposed for the 1969 show mounted by Jan van der Marck at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Art by Telephone, a show that is now considered historic. Like the thirty-five other invited artists, Bernar Venet gave instructions over the telephone to people he delegated to realize his work of art. In his case, it was to reproduce enlarged versions of four pages from a book on astrophysics.

Performed on May 1, 2022

Site-specific dimensions

Bernar Venet, 1961–2021: 60 Years of Performance, Painting & Sculpture, Kunsthalle Berlin, Tempelhof Airport, Berlin, Germany, January 29–May 30, 2022

Photo: Jerome Cavaliere

What could be read as an aside in my reflection isn’t one. The connection between Pile of Coal, Performance in Garbage, Accident, and Graph Theory or Statistical Theory of Communication probably isn’t formally obvious. However, the same determination on the part of the artist makes it possible to see them as belonging to a coherent whole that their formal differences do not change. Venet’s constant rigorous program is applied as much in the nuggets of anthracite spread over the floor as in the cold mathematical constructions he transfers without change to canvases that hang on the wall. It is a true north in both the making of the tar-covered cardboard pieces of his first forays in art and the gigantic sculptures, with the metal bars forming them quite simply obeying the principle of deconstruction and chance. The series of works from 1990 and 1991 called Random Combination of Indeterminate Lines perfectly encapsulates this option. The twisted steel bars wind over the floor, giving the impression of an active building site.[41] Placed inside the exhibition space or outside on a stretch of lawn, the tangled beams form the image of a cataclysm whose very origin is unclear. Separated each from each, or on the contrary rolled up together, one on top of the other, the metal joists litter the floor, playing out their distorted shapes. They’ve been freed of the pedestal, which at one time conferred the status of sculpture on three-dimensional pieces. For Venet, the ground, the floor, the pavement – these have become the only possible pedestals, offering their surfaces to the indeterminate evolutions of the materials he uses. In this regard, the artist was straightaway part of a movement that rejected the effects of the ostentatious display of the pedestal or base, and imagined putting out works of art directly on the floor. The historical example of the sculptural group The Burghers of Calais (1895), but also two earlier instances, The Kiss (1889) and Danaid (1890), had already tackled the question of the pedestal in the terms Auguste Rodin intended to pose it.[42] With these and numerous others that were to follow, a new way of envisioning sculpture began to take shape. From then on it would only grow increasingly important. Constantin Brancusi’s famous pedestals, the model of which is referenced by the very forms seen in the work displayed there, the stool-pedestal of Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel (1912), Carl André’s squares made of pewter, copper, and cast aluminum, and Richard Serra’s powerful Corten-steel sculptures are, among many other such examples, milestones marking out this rejection of the pedestal and its definitive end in the process of making sculpture. Venet’s Collapses and the works in the same vein are fully part of this questioning of the practice of sculpture and the principle of deconstruction connected with it. Such is the case with the 2009 Five Leaning Straight Lines, also made of Corten steel. One of the piece’s extremities rests on a parallelepiped made of the same metal, which seems to serve as a pedestal in this case, although it is in reality just a sort of resting place. There is a kind of irony in this display, a way of undermining ordinary codes. Indeed, the pedestal here is nothing more than a simple mass, unsuitable for fulfilling its usual function of elevating the forms it is entrusted with, fittingly receiving them on its upper surface all the better to glorify them. Viewers themselves don’t take in the sculpture, as they commonly do, from top to bottom. The eye views it the other way around and in passing takes advantage of this new arrangement being offered on the sly, since normally we might experience a certain feeling of inferiority when in contact with the raised-up work of art. The 1988 piece 245.5° Arc x 2 had already introduced the principle of the pedestal as a simple passive support. It served as the base for two curved lines which, resting on the ground, largely enclosed it. What’s at stake here is interesting since in this case, as in the one just before, the two installations lead to the pedestal’s being absorbed by the very element it is meant to display. This is in fact another way of effecting the desublimation of the work of art that Venet wanted and was indeed seeking out, a desublimation that is such a forceful presence throughout his body of work.

Rolled steel

290 x 300 cm

Bernar Venet: Indeterminate Hypothesis, Kasmin,

New York, September 12–October 12, 2019

Photo: Christopher Stach

Along these lines we find Random Installation of Points, which features imposing masses of more or less cylindrically shaped torch-cut steel. These sculptures are installed in the park of the Venet Foundation in Le Muy. Their title (Point) is cut into their upper surface. The point for Venet is an “element of space,” a “mark of form that is more or less determined,” or even “an abstract moment.”[43] Its proliferation on the wall marks a decisive step in that it allows the wall to be a surface and inscribe homogeneous forms there. But it was to truly become concrete when it entered three-dimensional space. The volumetric Points, of increasingly greater size, aren’t the end of a cycle, the way a series of the same name was in the work of Francis Picabia. No, they represent a new direction for the artist’s experimentation, teeming with possibilities for new works.

Nearly the totality then of the sculptures done by Bernar Venet do not have pedestals and are displayed directly on the floor or ground, for they are indeed naturally, irredeemably welded to the ground, as it were. When they thrust up and into the heavens, as recent constructions do (Disorder: 9 Uneven Angles, 2015, or Arm at Rest),[44] the works are anchored in and rise from that ground. Such that we imagine the pedestal as being buried in the ground, disappearing entirely, the better to make room for the emerging forms. But most of the time, the sculptures have their seat, their base directly on the ground, while their weight, very often significant, ensures their balance. In this sense then, the twelve arc-shaped beams seen in the Venet show at the Palace of Versailles are now tossed on the ground in an elegant disorder. Lying atop one another, they form a complicated tracery that undoes the simple, obvious perception of geometric line, be it curved as it is here.

Corten steel

Site-specific dimensions

Bernar Venet: Drawing with Steel, Busan Museum of Modern Art, Busan, South Korea,

September 20–November 18, 2007

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Busan Museum of

Modern Art

The indeterminate lines constitute an important step in the artist’s work in that they concentrate in themselves all of the parameters he has always pursued, viz., chance, material tension, mass, and of course the attraction of the earth, which they take advantage of most. The very first of these, Position of an Indeterminate Line, dating from 1979, was not yet freed from the wall. Done from a hand-drawn design that was then enlarged on a piece of plywood and cut out, the piece meanders over the wall, unreeling its complex twists and turns from one end to the other. Soon enough the lines would desert the wall to occupy space.[45] All of them would play out their dynamic form in whatever particular space that was home to them, infusing it each time with their beautiful energy. One inevitably thinks of the works of certain artists who also produced drawing-sculptures, Pablo Picasso and his Monument for Guillaume Apollinaire or his drawings done in a darkened space using a flashlight; Calder, sculpting portraits of his friends from wire (Miró, Léger, and so on); Norbert Kricke and his finespun metal structures; Fred Sandback and his Minimalist constructions fashioned from wool yarn. Like these examples, Venet’s indeterminate lines take over the space, transforming it by inscribing a kind of paradoxical gesture in it. The decision to transpose in metal – a hard material that is hard to work – a mere line, flexible, liable to fluctuate, and coming from a design quickly sketched out on paper, is indeed a true paradox of sorts. The fluid, briskly drawn image that the hand consigns to the sheet of paper thus takes shape and becomes a dense coherent object. This calling into question is one of the highlights of Venet’s body of work. The line couched on the paper doesn’t lose its flexibility for all its being transposed to wood and later metal. It has simply learned to dominate its turbulent developments and proliferating coils and whorls. And even when the latter became excessive, profuse, and riotous, as in the recent GRIBs, they are subjected to the stern discipline of the technology that midwifes their existence in the particular space. Ending as bars that are curved and twisted by the play of various tractions exercised on them, pulled and wrapped around themselves, lines the artist draws on paper in gestural exercises that are repeated over and over become true material objects that belong to the surrounding space in which they are inscribed, now and forever.

Corten steel

240 x 1300 x 1600 cm

Le Muy, France

Photo: Maxime Bruyelle

Done in rolled steel, the curved bars of 84 Arcs / Disorder (2013) also obey the dual principle of gravity and chance. Divided up into twelve distinct groups, they rest directly on the ground. As reversed curves, lying on their backs, so to speak, they point their two ends towards the sky, becoming those “open lines” that Jean-Louis Schefer describes, each one of them “imposing its mass, (and) with its mass its folding axis and the merciless plumbline that imposes a series of gravity points.”[46] The arc naturally integrated Venet’s vocabulary, as if its place was obvious. The arc, moreover, has long figured in his work. It already surfaces, for example, in the diagrams from the 1960s, notably in the representations of parabolas and other mathematical functions.[47] It can be seen as such in the acrylic paintings in which the shape of the stretcher matches that of the drawing, faithful in that respect to the principle behind the Shaped Canvas.[48] It continued to develop by taking on a more complete independence when the artist cut the shape out of wood, covered it in graphite and hung it on the wall. It achieves even greater independence when – as a bent metal beam with different degrees of curvature – it rests on the ground or is simply leaning against the wall on one of its faces or its two ends. It finally sloughs off all vertical support when it becomes a full-fledged object, a machined material set on the ground and developing its sculptural potential alone, entirely on its own. Arcs is the name they would eventually go by, as was the case for the Straight Lines, Angles, Points, and Indeterminate Lines. The object is announced in its title, which defines it and offers the primary and essential piece of information. With the arcs, the number of degrees that constitute each of them is also stated, which makes it possible to differentiate arcs from each other and especially show the variety that exists in the output. Because Venet’s body of work is clearly and unmistakably varied. An indefatigable maker of aesthetic objects, the artist is permanently in search of new solutions and novel challenges that he applies himself to, while remaining faithful to the very principles he has set himself and the lines of development he has chosen. The piece he imagined producing for a show scheduled at the Dunkirk Museum in 2019 corresponds fully to his demands. Some 120 arcs, arranged on the floor in three parallel columns, were to be given a forceful push to make them all tip over in succession and fall on top of each other. As a monumental game of dominos – the piece as a whole would weigh no less than 200 tons – the fall of the arcs, neatly lined up before the lateral thrust, would pull them into a new chaos and bring out an improvised figure whose outlines chance alone could trace. As in the other Collapses, disorder followed order; indeterminacy, ordered composition; dispersal, reasoned construction. In this work to be, as in many others created long ago, Venet confirms his propensity for the off-limits and the monumental. Like Yves Klein, who, after Henri Matisse, brought to light the power of blue covering large surfaces,[49] and following the example of Arman, who likewise revealed the force of an object with many copies accumulating in a space, Venet turned to the gigantic by choice. And the example set by the Americans surely played some role in those choices. A contemporary of the practitioners of Land Art, the French artist also opted for spectacular sculptures, well aware of the visual and emotional impact they could hardly fail to have on visitors. The immense accumulations of metal arcs in the Versailles installation and those in Dunkirk, equally impressive, are the most radical examples of this determination. Yet however imposing they are, such sculptures undermine the codes they are usually seen as conveying. In Western culture, the arch, close relative of the arc, expresses the power of authority. Erected at city gates, the arch had a portentous, even pontificating presence, leading the way for parades and other demonstrations of force. It is the architectural figure of triumph and success. In the field of construction, the arch is also a centerpiece. It allows an edifice to rise and guarantees it an utter stability that can be relied on. Venet plays with such properties and the symbols linked with them. Surrendering his arcs to the force of gravity, committing them to an irreversible fall, leaving them scattered on the ground as they have fallen, the artist exhausts the sovereign image that arcs and arches possess and brings their warrior symbolism crashing down. Naturally it would be rash to see in his deconstructive gestures something other than the wish to transgress artistic principles. Shake up, overthrow, disorient, swap in and out, switch around… these have always been his choices. Bernar Venet has indeed always been determined to establish a new formal vocabulary through methods that are themselves new.

Corten steel

700 x 4100 x 1600 cm

Le Muy, France

Photo: Maxime Bruyelle

The Collapses display other geometrical figures than the arc. The angular figure, for instance, has also been given a similar treatment. Having appeared early in his work, the angle has been endlessly worked and reworked in a variety of forms. It was already present, like the arc, in the depictions of mathematical functions, like the 1966 piece titled The Straight Line Represents the Function y = 2x + 1. The oblique straight line that cuts the X- and Y-axis at their intersection indeed forms an angle the degrees of which can be easily calculated. Those degrees are plainly stated in a drawing featuring an isosceles triangle which also dates from 1966. The drawing includes both a collage using a page cut from the book out of which Venet copied the figure, and the following phrase: “trigonometric ratios of 45°, 30° and 60° angles.” In the following decade, the angle was to take on a more complete independence to become the only subject depicted. Salient, acute, obtuse, adjacent, additional, combined with another and, in that case, incorporating the bisector, the angle is traced in graphite or oil pastel on sheets of paper, painted on canvas in acrylic, cut out in wood and covered in pigment, and later, in the 1980s, done in metal, finally attaining the status of three-dimensional sculpture.[50] It was in the latter iteration that the form held pride of place in the garden of the Palazzo Cavalli-Franchetti in Venice during the 56th Biennale in 2015; it stood at Union Square in New York, and on the square before La Commanderie de Peyrassol in France; and, at its peak, its vertex, it bestrides the glass-clad Westech 360 Building 2 in Austin, Texas. A figurehead indicating with its point its future as a conquering figure, the angle would soon go through a similar arc, similar, that is, to the arc’s. In the series of Collapses, it is always present in pairs, threes, nines, even several dozens, but, accepting to bend to the law of gravity, it loses its panache (while keeping its haughtiness!). It still occasionally needs the wall to find its stability, as in Collapse: 3 Angles from 2012. The floor, however, became its stamping ground and the handy repository of its chance contortions. Piled atop one another in no particular order, the angular metal beams echo the Pile of Coal from the start of his career, even if the material making up the former clearly differentiates the two. The idea presiding over their common outcomes is laissez-faire, the minimal intervention of the artist, his summary gesture devoid of any particular attention by which coal and metal assumed a particular form. Isolated unstable crutches or tangles impossible to undo, the metal angles extend the storyline of order and disorder, and in their sudden inertia afford a glimpse of the ear-splitting din that accompanied their fall. Their physicality can be apraised directly without the mischievous innuendo that François Morellet, that other sculptor of angles, lets peek through in his installations.[51] And without the universal symbolism bound up with both theseries of works by Michelangelo Pistoletto called Divisione e moltiplicazione dello specchio, and the corner pieces that Joseph Beuys did with his legendary materials, fat and felt. Bernar Venet’s angles actually have more of a kinship with the angles that predominate in the work of Tony Smith (Tau from 1965, for instance, or Seed from 1968); or those of Frank Stella, so much a part of his series Parzeczew from the early 1970s; or again those that structure nearly all of Sol LeWitt’s sculptures. The angle is a figure that runs through the whole of art history. It is the first element that serves to define the fundamentals of perspective in the work of trecento and quattrocento artists by ordering the pavements, columns, and pediments of the represented space. Its presence would continue to grow over the centuries that followed before culminating in the twentieth century. The angle was no longer then the tool that brings order to an environment; it became the very subject of painting. The artists of all the Constructivist schools would select it as one of the primal figures that are essential to the organization of the new pictorial space they aspired to create. Piet Mondrian limited the angle’s opening to 90° and – because he saw in it the guarantee of a universal truth – strove to promote it everywhere, both indoors and out. When others like Theo van Doesburg, Bart van der Leck, or César Domela would venture to break the rule of the right angle, when certain other actors in Neo-plasticism were to transgress the dogma of orthogonality, a falling-out was all but inevitable since for Mondrian, the angle can only be a right angle and admits no other configuration. In the work of this practitioner of Neo-plasticism, it was an intangible formal rule whose basic premise lies in nature itself via, for example, the verticality of trees and the horizontality of the sea. For him, orthogonality is an absolute formal prescription because it is an indisputable precept of life which the human condition must respect at all costs. Straight, acute or obtuse, closed or open, the angle draws particular attention in the output of modern and contemporary artists. Malevich, El Lissitzky, and Moholy-Nagy chose it from the outset as one of the primordial figures of modernist grammar at the same time that the Italian Futurists were seeing in it the very symbol of speed and combativeness. Venet was attuned to what other artists had gotten out of this form, but was to introduce it into his work without any metaphorical resonance. For him it is a mere geometrical figure, as are the arc and the straight line; by no means would he venture to lend it some parabolic dimension, be it parable or parabola. The relationship of equivalency which the artist sees as existing between the three figures is moreover visible in one of his works. There is one collapse where angles,straight lines and arcs are indistinctly mixed, creating a hulking mound made up quite simply of straight and rounded segments. Curling around themselves or resting on top of one another in an obvious disorder that the artist makes no attempt to control or restrain, the forms look as if they’ve been thrown down on the ground, thus underscoring the impression of confusion and disorder. Their ends are not always visible but when they are pointing into space, they display scars and other signs of the violence done by metalworkers in the course of working the steel. These complex entanglements are worth observing from several points of view. There is indeed much to be had in looking at them from different angles. Then comes to light the subtle play of empty and full space, void and solid; and the play – just as delicate – of cracks and clinks of light in this titanic muddle of impossibly entwined steel. It is those breaches and gaps, by the way, that allow us to better perceive the formal qualities of the material employed, Corten steel. The variations of its powdery hues, the deft mastery of its roughness, the traces left by oxidation – such features appear only to those who take the trouble to look closely at these heaps of iron.

Weathered steel

17.5 x 170 x 100 cm

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Variable dimensions

Rolled steel

Bernar Venet: Another Language for Painting,

He Art Museum, Guangdong Province, China,

October 1, 2021–March 3, 2022

Photo: Liu Xiangli

Steel

Line: 1700 cm. Cube: 150 x 280 x 140 cm

L’Hypothèse de la ligne droite, Fondation CAB, Brussels, Belgium, February 12–March 14, 2020

Photo: Laurent Bradajs

The collapse in question is the formal translation of the lexicon of words that Bernar Venet put together long ago. The words passing beneath readers’ eyes are indeed indicators of the artist’s method (or antimethod): Disorder / Instability / Rupture / Dissipation / Imbalance / Antagonism / Entropy / Disorganization / Disturbance / Unpredictable / Deviance / Uncertainty / Randomness / Disintegration / Transition / Unexpected / Turbulence / Chance / Collision / Irreversible. But more generally, Venet has been able to translate through words what he has done in his visual body of work. His bilingual anthology called Poetic?Poétique ? is full of texts that confirm his commitment as an artist and faithfully reproduce what he has undertaken elsewhere. “The Accident Pieces Are Related to” (the French title is different, “Hommage à l’accident”) is a series of terms that suggests disorder, randomness, and unpredictability – those essential words on which are grafted other nouns, i.e., dissipation, uncertainty, turbulence, and disturbance.[52] There are even words that can’t be read, saturated as they are by ink, blurred and darkened by succeeding layers of print that end up muddying their visual features and along with them the meanings they convey. “Saturation (1)” and “Saturation (2)” are thus gradually overwhelmed by the thickening black ink, like the pieces of cardboard covered in enamel paint, the tar pieces, or the pile of coal back in the 1960s.[53] These two series culminate in another poem titled “Blackboard” in which the artist associates different terms (photography, music, theater, sculpture, etc.) with the qualifier “black.”[54] The alphabetical indexes of “Scientific Vocabulary Poem (1), Alphabetical Index” and “Scientific Vocabulary Poem (2), Alphabetical Index” feature a long series of names of materials (including elastomers, polymers, and all kinds of resins) that are listed as entities complete unto themselves, drily enumerated, without any other attribute, just as the canvas surface of a number of Venet’s paintings presents functions and other diagrams objectively reproduced there.[55] Finally, his poem “This Is Why” excellently points up the parameters of destabilization and precariousness which are so crucial in his work. When the artist writes, in a line we might take as a kind of conclusion, “This is why form is organized in imbalance and instability,”[56] he lets the inevitable consequences show on his sculpture. From Performance in Garbage to the Collapses, naturally by way of the Pile of Coal, Bernar Venet entrusts to forces that elude him a significant role in the production of his art. With them the hypothesis of gravity is largely verified.

Performed on January 1, 1995

Le Muy, France

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Corten steel

171 x 865 x 360 cm

Le Muy, France

Photo: Courtesy the artist

Corten steel

Length: 751 cm. Cube: 120 x 250 x 300 cm

L’Hypothèse de l’arc, Galerie Von Bartha, Basel,

May 22–July 19, 2014

Photo: Courtesy the artist and Galerie Von Bartha

Corten steel

500 x 2200 x 1600 cm

Le Muy, France

Photo: Maxime Bruyelle

Corten steel

500 x 2200 x 1600 cm

Le Muy, France

Photo: Maxime Bruyelle

Performed on August 25, 2005

Le Muy, France

Photo: François Fernandez

Corten steel

223.5 x 812.8 x 289.6 cm

Bernar Venet: Gravity, Kasmin, New York,

November 4–December 23, 2022

Photo: Diego Flores

November 4–December 23, 2022

Photo: Diego Flores

New York, November 4–December 23, 2022

[1] Bernar Venet, “Dans et hors la logique, entretien avec Catherine Millet,” art press 220 (January 1997), 26.

[2] Thomas McEvilley, analyzing the photographs of the performance, brings up the figure of Diogenes, as well as the hobo and the drunk. See Thomas McEvilley, “Déplacer la gravité du moi,” Bernar Venet (Lyon: Artha, 2002), 15.

[3] The first instance of waste and rubbish in the field of art seems to have been the Ash Can School, the early-twentieth-century group of American artists that formed around the painter Robert Henri; their works depict scenes of daily life in working-class neighborhoods.

[4] This experimentation with the unsurpassable and the connection made with refuse was more recently touched on by the Guatemalan artist Regina José Galindo. In a performance called No perdemos nada con nacer (We Lose Nothing by Being Born, 2000), the naked artist was placed in a transparent plastic bag and tossed on a public garbage dump, where she was left for several hours. The political scope of the piece is obvious. As is always the case in her art, the work decries the violence that is endemic in the country, the foremost victims of which are generally women.

[5] Informed quite early on about what was being done here and there, Venet wasn’t unaware of the demonstrations done by Yves Klein and Arman. He has talked about this, moreover, on several occasions, and has stated for the record what the two artists brought to his own work. See Millet, “Logique,” 127.

[6] There is no doubt that in those crucial years this option was shared by several other artists. The Japanese movement known as Gutai, through its very name, refers to the object’s materiality and, along with that, the materiality of the body, as the Viennese Actionists attempted to do in a far more violent manner. In a different register, the work Piero Manzoni proposed with his Merda d’artista (Artist’s Shit) reached a limit that is likewise unsurpassable.

[7] Among the happenings and acts involving restoration and maintenance, I would mention Ben’s gesture in 1968 when he decided to sweep his street and clean the central hall of Nice’s train station. I would also recall here Joseph Beuys’s performance Ausfegen (Sweeping Up), which he did in West Berlin in 1972. During this civic act, the German artist, assisted by two of his students from the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf, swept Karl Marx Square in West Berlin.

[8] Aude Launay sensibly observes, “It seemed to him he was in the presence of a painting that exceeded the classic concept of the latter as the result of the actions of an artist. A painting that apparently had as its fundamental principle gravity and as a vector contingency. A painting and, above all, a situation that he immediately got down on film, the beginnings of a reflection on the nature of the work of art that prefigured the reflection of those who would soon be known as the Conceptualists, and whom he was to join for a time.” Aude Launay, “Bernar Venet,” 02 (2017), http://www.zerodeux.fr/news/bernar-venet/ (accessed October 5, 2022).

[9] Arnauld Pierre, “Bernar Venet – Le discours et la méthode,” Bernar Venet (Milan: Giampaolo Prearo Editore, 2000), 51.

[10] In his book, Thomas McEvilley shrewdly makes the connection between Yves Klein’s leap into the void and Bernar Venet’s fall. That fall which Klein “had always concealed and avoided bringing up,” Venet fully laid claim to it and “showed its true consequence, affirming the supremacy of matter and its laws over mind and its aspirations to flee.” McEvilley, Venet, 16.

[11] See McEvilley, Venet, 12.

[12] Bernar Venet, La Conversion du regard, Textes et entretiens, 1975-2010 (Geneva: MAMCO, 2010), 81. The title Venet gave to this piece in French (Lutte avec la terre glaise) is not quite right. The work is generally called Challenging Mud, and does indeed date from 1955.

[13] Venet, Conversion, 82.

[14] After his initial effort in the studio that he was allowed to set up in the attic of his barracks in Tarascon, Venet distributed the five drawings to his barracks mates.

[15] The Symphonie monotone-silence (Monotone Silence Symphony) composed by the artist Yves Klein accompanied the movements of the models’ nude bodies, while the text-based score of La Monte Young’s Composition 1960 #10 to Bob Morris, which reads, “Draw a straight line and follow it,” guided Paik’s gesture.

[16] The artist’s performance took place during the Perpetual Fluxfest that was held on July 4, 1965, at the Cinematheque in New York.

[17] See Thierry Kuntzel, “Bernar Venet: logique du neutre,” Conversion, 11.

[18] See “Conversation avec Eddy Devolder,” Conversion, 57.

[19] For a lack of financing, the proposed project (in this case, a drawing) alone was sent to Céret. Only later was the sectioned PVC pipe done. The simultaneous display of the tube and a drawing-design on tracing paper is considered a whole. Displayed in this way at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Nice, Tube No. 150/45/60/1000 from June 18, 1966, echoes works by Joseph Kosuth in which the object, the photograph of the object, and the dictionary entry describing it are shown in the same space. See in this regard the artist’s own critical observations. Venet, “Entretien,” Conversion, 121-123.

[20] The latter work, like the 1966 Correction of Cog Teeth, should be compared with Francis Picabia’s painting titled Le Fiancé in order to point up the differences. All of these pictures show trapezoidal gear teeth and slotting but clearly the Dadaist spirit and (dare I say?) ironic grinding of the gears that comes with it are totally absent from the conceptual artist’s works.

[21] Venet readily admits the importance of the Russian avant-garde artists’ contribution to his own output: “In the twentieth century after Rodchenko’s 1920 Construction of Distance, it was surely Vantongerloo, starting in 1930, who first thought of giving his sculptures titles like y = ax2 + bx + 18,” Venet, “Entretien,” Conversion, 136.