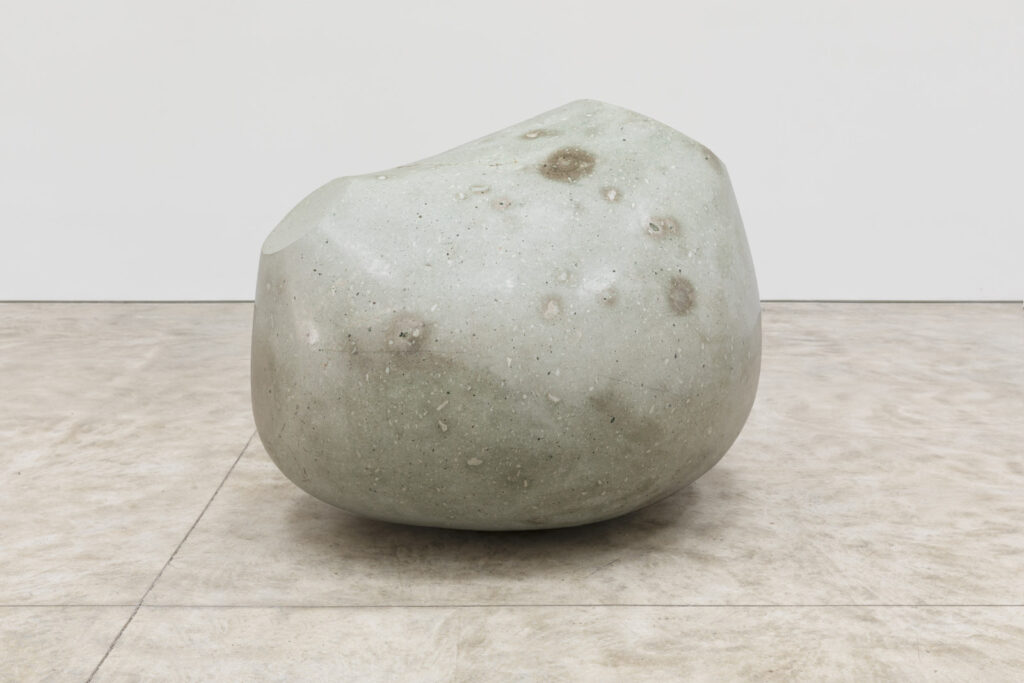

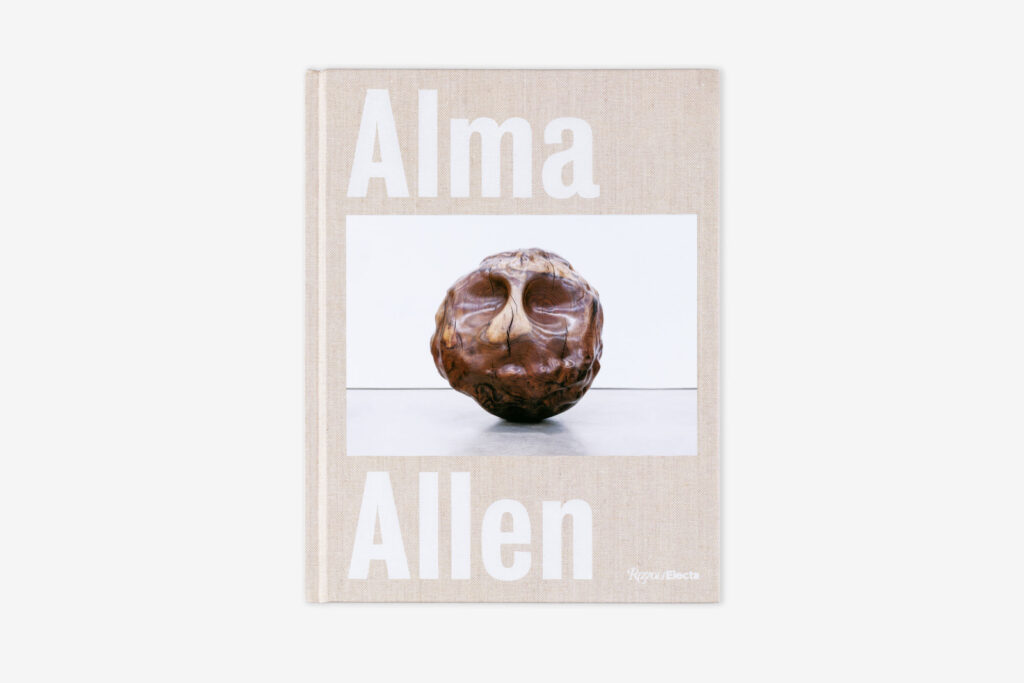

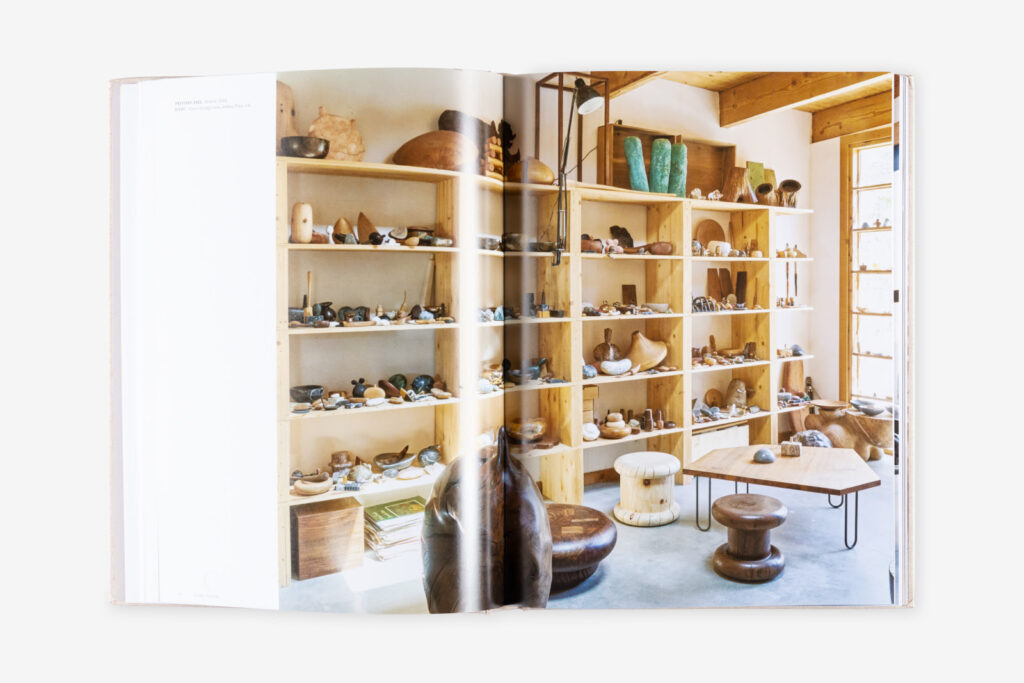

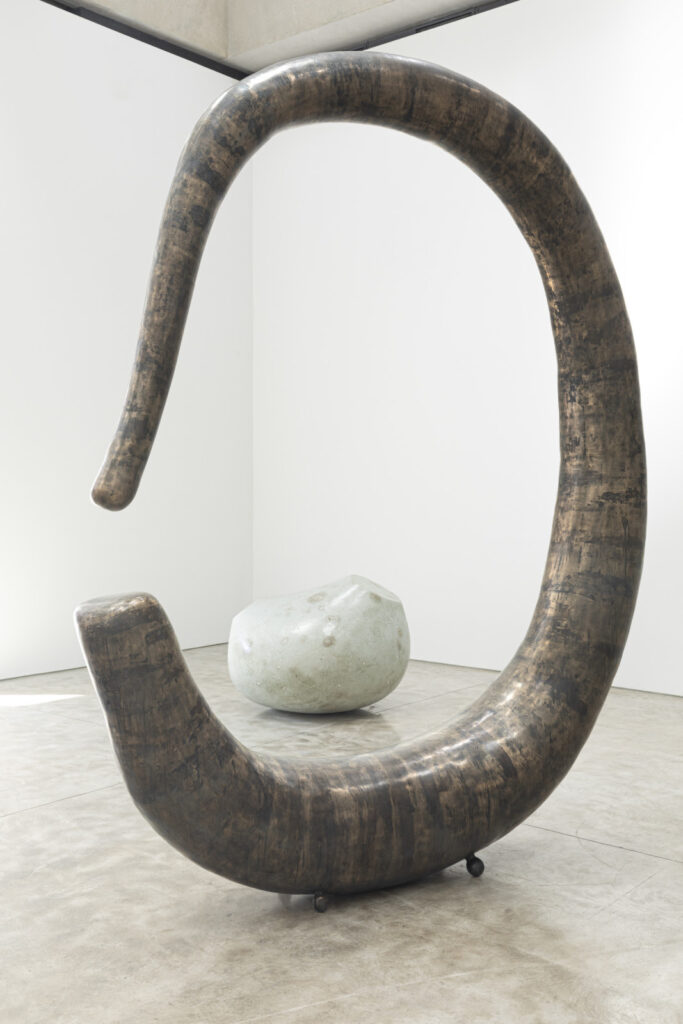

On occasional Saturday mornings, Kasmin shares essays and interviews from the gallery archives. Alma Allen's first solo exhibition at Kasmin went on view at 509 West 27th Street between January 23–March 4, 2020. Allen's first major monograph, published by Rizzoli Electa, featured newly commissioned photography of Allen's studios in Joshua Tree, California, and Tepoztlán, Mexico—two spaces designed and built by the artist. Texts by Glenn Adamson and Douglas Fogle illuminate Allen's work, which is painstakingly made in foraged wood, sculpted marble, and cast bronze.

Su Wu: I just found an early note from you, about this Carl Jung quote we both love, and I don’t really want to talk about Jung but I bring it up because it seems as good place as any to start this conversation, to acknowledge a certain futility, the likelihood that we’ll try really hard to say the wrong things. This is the quote: “Loneliness does not come from being alone but from being unable to communicate the things that seem important.” But, one of the things that strikes me about you is that you’re an optimist. So there’s hope for this conversation yet! And I wondered if you think being an optimist is also what makes you so restless?

Alma Allen: I’m definitely optimistic but I think it makes me more reckless than restless.

In a situation where you don’t have resources, you have to be reckless.

How I work is I often throw things into a jumble and cause as much chaos as I can and try to rearrange it while it’s happening. I can’t see things very clearly except for in the very quick and frenetic state of working. I mean, I’m not really that interested in what I can imagine easily. And what I can imagine is fleeting, things I see out of the corner of my eye, and I don’t think I can get there consciously, like a real cognitive plan won’t ever get me to the goal. I’m just not a planner, and I get really bored if I’m just working through something that I already see. I want to use the process of working.

It’s not that I have an identifiable gesture, it’s that there’s a regularity to the things I find attractive

Alma Allen

SW: You’ve mentioned that sometimes these visions of shapes come to you all at once, but that more often they come in the making, that your hands have their own knowledge and memory. And that to me seems sincerely confusing, I mean, I think that captures part of it . . .

AA: I was thinking about it this morning. I made a small piece these last few days on purpose just to think and see the process, to analyze it, because I’ve never really done that when I’m working. There’s a great deal that’s from the feel of something else, that gets transmitted. It’s a little harder in the large scale, but in the smaller scale and in the models for the larger pieces, I remember a curve, a shape better with my hands than with my mind. I don’t really trust my mind. I trust my fingers a lot more. You hold a lot of information and a lot of knowledge in your senses, your sight or your hearing.

SW: Right, the identifiable gestures, and the skill and also the impulse, maybe, but not the struggle. Your hand gets you part way there, but then there’s the stuff that gets left unsaid. I guess, in question form: how much of your work is intuitive and how much of it is deliberation?

AA: It’s not even that I have an identifiable gesture, it’s that there’s an irregularity to something that I find attractive, something from the natural world, something from a log or an elbow. The more times it gets changed through the hand, it becomes designed, it becomes regularized. I think that a curve can transmit so much information, so much, but not one, necessarily, that’s a continuous exact radius. Working with your fingers and your hands you know that better than your eyes. Your hands are way more adept. I start deliberately but I don’t finish that way.

SW: How have you gotten better?

AA: If anything you get better because you try not to be perfect. You get used to throwing things into unrest and grabbing at it, and then grabbing the worst of it–often the worst becomes the most important work, the ones that I’m the least comfortable with. The more I think about it, the more difficult it is for me.

SW: It brings up for me that question of whether things need us to explain them, or if we should just revel in their presence, rather than trying to replace them with words that fall short. I mean, how do you think of the physical in your work? Like both the physical world as opposed to the biological world, these material choices in stone and wood in contrast to flesh, but also the physical as in physical activity, creating from something inanimate.

AA: Natural material breaks, and it has cracks, and you have to change your direction all the time, and there are changes in the color of the material. Sometimes I work with clay where this never happens, it’s plastic. I mean it has its own elasticity and it has its own ways, but you can always go back. With reductive sculpture you can’t really go backwards, which, for me, is helpful. I don’t know what I would do with it. I’d become paralyzed if I could go backwards. I’d be at the same point always.

SW: You’d mentioned earlier that there aren’t many reductive sculptors anymore. It’s hard work, but it’s also a counter to certain impulses, the stripping away instead of the building up.

AA: And it’s not referential. I don’t really feel a part of popular culture so I don’t really feel comfortable making references from it. I’ve never really felt continuous enough with popular culture to comment on it. And I appreciate work that does, but it’s so far from my own. And I think that’s where it leaves me, because there’s no commenting in reduction.

SW: What happens to your dust?

AA: I hope I don’t breathe it. I breathe some of it. I eat some of it.

SW: I want to go back a bit to the idea of not being contiguous, not fitting, or outside certain established readings and trajectories, that there’s not this whole enterprise around it already. But that also makes it, I think, a little bit lonely, that the work is somewhere beyond this conversation we’ve already figured out how to have. And you live in a pretty inhospitable climate, in relative isolation. Have you deliberately sought solitude? Or is it a byproduct to what you need to make your work?

AA: I’m very noisy. And I do really like working. There are moments where making work allows me to be outside of myself. I think most people must have that in the things they like to do, and it’s made me sort of addicted to work. And it leads me to go live where nobody is around.

But, I don’t know, I’m a person of the world.

SW: “I’m a person of the world?” Did you just say that?

AA: No, I mean I’m interested. I’m a little naive, but I think that’s also a bit protecting.

SW: Do you want to talk about your childhood?

AA: Not really. I told you some.

SW: I don’t want to put words into your mouth but I did really love the imagery, the idea that there might someday be some child walking around the desert in the late afternoon delaying the hours before being elsewhere, finding one of your unsigned carvings sitting in a pile of rocks.

AA: That’s quite important to me. I mean often my intention with my work is not something that I think will be important to the viewer; it’s very personal. But I’m trying to provide a vehicle for the viewer to have their own experience. I’ve often made work and left it in places or found funny ways to show it. The viewer doesn’t have an approved reality, an institutional reality–they really have to make a leap of their own. It lets them experience something to complete the artwork. And I think the more they know about me, or the more they try to interpret what I meant by the work, the less they’ll be able to do that. So I’ve often stayed pretty hidden. And it’s why I leave pieces.

As a child I left pieces for the Indians because I was convinced they were still out there, they were just too smart to be seen, because they knew we were not up to any good.

SW: Can you talk a little bit about the inadvertent poetry of leaving things behind?

AA: I don’t think there’s anything better for an artist, at all, than that your work gets lost, and then someone discovers it and creates in their own mind what it is, and what it was meant for, or even if it is art. They have to make that leap, and I really think that completes the artwork, in that instance. And for each new person it’s a new instance. I’m such a sap.

SW: Also, not signing the works! Which is incredible to me. And this happens less often now, I know, for a whole host of practical reasons, but I’m fascinated with this thread of disappearance. Do you think people who know you have a different interaction with your work? I mean not just that they have the privilege of information and access, but what actually gets lost the more we know about the specifics of a piece or person?

AA: It may not be as bad as I think, not quite so dire. That’s probably just my shyness. But not signing things, especially the smaller works that I made for many years: they’re really meant to be held in the hands and not sit somewhere. So they’re not objects that were meant to display at a certain angle, or in a certain way, and if I sign them it predetermines their orientation and their location, which I don’t want to do. They can continue to create something, because of interaction among the objects. I mean it’s not a very contemporary thing to say; most of my answers are not very good contemporary art answers. I’m a bit of a, a little bit of a . . .

SW: A bit of a what?

AA: At this point I’m purposefully naive. I mean I’m not primitive; I’m self-taught but I haven’t willfully not read a book. I’m never entirely convinced that everything is always perfectly set to how it is. In a very slight way. I don’t mean that, oh no, we’re inside of a bubble on the eye of a whale, I don’t mean that at all. I just mean that I’m open to the sense of wonder, open to things changing.

SW: Do you have a sense of what triggers those changes?

AA: Something outside, some circumstance. This is strange. Don’t you worry?

SW: Of course. I feel distrustful of people who don’t worry.

AA: Right, but you make so many snap judgments, you seem so confident, you seem like it, but that’s the outside.

I don’t think there’s anything better for an artist, at all, than that your work gets lost, and then someone discovers it and creates in their own mind what it is, and what it was meant for, or even if it is art.

Alma Allen

SW: What I worry about is the other edge of that, where overvaluing discernment turns you into a deeply dissatisfied person or you forget how to be kind. I just think my personality type is a judger, just judging and complaining constantly.

AA: That’s what I find so fascinating about you. You think you will be happy?

SW: Who cares. What would you do with happiness? Seriously, what good is it? I don’t know; it doesn’t seem like the noblest pursuit, just something to the side of it. And you seem to often be in some sort of mishap.

AA: I hurt myself all the time. [Holds up injured thumb]

SW: Well I can add that to this list: a shattered leg from riding a motorcycle in the mountains . . .

AA: I love to go fast.

SW: . . . a truck hauling a piece of marble from Colorado that breaks down outside of Vegas, carving things so hard that your hands break down. What’s your relationship to injury, like, is there a swagger to working in a form that requires some physical strength?

AA: I mean maybe when I was younger there was a bit of swagger. But it’s funny, I’ve always made small work. There’s really not much swagger in making small things. And I hide myself quite a bit. I’m not central, I don’t want to be central.

SW: When we first talked for this interview, you mentioned a few artists whose work you see as simpatico, and it surprised me–it was not at all how I would have categorized your work, if I had to. I thought it got at something that might be interesting, and the language of your work or the value system that you see in your work.

[Silence]

SW: Fine, okay: who are the artists with whom you share an affinity and why?

AA: No, I knew that was the question. I’m just looking at the list I made. I mean, many people maybe haven’t even taken up stone sculpture because of Brancusi in the beginning of the century. He’s by far the most dominating creature of any sort of art form, music or otherwise. I can’t think of another giant that sort of bullies everything. It’s a bit unfair, and it’s probably driven a lot of people off sculpture. He wasn’t conflicted or crazy. He was very centered, the work was.

And I’ve been influenced as much by writing or music, as by art. I love the writing of Samuel Beckett; it’s like a fever dream. I have a really strong identification. It must be that the brain thinks in the same chaotic patterns and tries to make sense of the chaotic patterns. I find it kind of soothing. I think the idea of contemporary art is a pretty new fabrication and I don’t think the artists working in the past would have thought of themselves as contemporary as opposed to part of a long human flow, the continuation of art as opposed to the contemporariness. I’m going to get really good at art babble, though. I’ve never had once a review of my work, and I’ve never been challenged, at all. Since I didn’t go to school, I really have not had to defend my work, or even been placed in a position where it’s criticized. It’s going to be a very interesting new process for me. And that’s like the central thing that many artists go through–that experience–and work for and about, that feeds so much of what they do.

SW: What do you hope the criticism is?

AA: That’s part of what I miss, being on the outside. It’s all positive. I kind of hope they’re mean. A little bit.

SW: The right meanness is perfect. It’s just how much you believe your own myths.

AA: I can’t slough it off, I don’t give up completely. Maybe it’s this utter optimism. The last bit, that I can’t let go, is that there’s just momentum, and our physiology interacts with a really base sort of energy that propels humans forward, that we can sort of interact with, not in a purposeful way. It’s whatever causes animals to procreate and stars to keep drifting apart. As a kid I was convinced at times I could imagine it, when I was running really fast in a field and went into a sort of trance, and you could see the universe moving.

SW: I said I didn’t want to talk about Jung, but I have this note from you — the “psychomotor domains of understanding.” [laughs]

AA: That was my past, this attempt to make an artist statement. And that’s basically what it means:communicating through other senses and thinking with other senses. I don’t think it’s just communicating.I believe the hands and the eyes can think, they’re cognitive. Or maybe it’s just me and other people canjust sit quietly and think. But I don’t very well. I actually like hard work and lots of continuous, repetitivecarving to separate the mind away so you can actually think. Like too-fast motorcycle rides because if youhave so much, so many things happening, maybe it’s like a lazy meditation, where you are able to have ameditation without having to go through just sitting there, quietly. You can have these sorts of meditativestates through intensive action.I get addicted to work. I have something that I like to do and I’ll try to remind myself to look up to see if it’sgoing to rain, and another hour or two hours will go by working, when I’m outside, before I will rememberto look up, because I get really intensely involved in that state.

SW: Have you always been that way?

AA: I’ve always been that way since I was a little kid. It’s that restlessness. I’m sort of anxious. It’s embarrassing a little bit. I just think much, much better with a lot happening. But it’s not just things happening. When you’re working very intensely on something, through physical motions, at some point you can see clearly and your hands continue working. There’s a moment of transcendence your brain allows you by needing all of your senses to keep what you’re doing accurately, and that lets other parts of your brain open up. And that’s the state I’m addicted to, and I look for things to reach it.

SW: What keeps you from reaching it?

AA: I mean often I’ll think really clearly in those moments when I’m halfway awake. But as soon as you wake, it changes, and it changes your ability to have a fluid way to see things. Like, you’ve told me that the right word came to you in the morning; morning is an interesting time.

SW: What do you hope the criticism is?

AA: That’s part of what I miss, being on the outside. It’s all positive. I kind of hope they’re mean. A little bit.

SW: The right meanness is perfect. It’s just how much you believe your own myths.

AA: I can’t slough it off, I don’t give up completely. Maybe it’s this utter optimism. The last bit, that I can’t let go, is that there’s just momentum, and our physiology interacts with a really base sort of energy that propels humans forward, that we can sort of interact with, not in a purposeful way. It’s whatever causes animals to procreate and stars to keep drifting apart. As a kid I was convinced at times I could imagine it, when I was running really fast in a field and went into a sort of trance, and you could see the universe moving.

SW: I said I didn’t want to talk about Jung, but I have this note from you — the “psychomotor domains of understanding.” [laughs]

AA: That was my past, this attempt to make an artist statement. And that’s basically what it means:communicating through other senses and thinking with other senses. I don’t think it’s just communicating.I believe the hands and the eyes can think, they’re cognitive. Or maybe it’s just me and other people canjust sit quietly and think. But I don’t very well. I actually like hard work and lots of continuous, repetitivecarving to separate the mind away so you can actually think. Like too-fast motorcycle rides because if youhave so much, so many things happening, maybe it’s like a lazy meditation, where you are able to have ameditation without having to go through just sitting there, quietly. You can have these sorts of meditativestates through intensive action.I get addicted to work. I have something that I like to do and I’ll try to remind myself to look up to see if it’sgoing to rain, and another hour or two hours will go by working, when I’m outside, before I will rememberto look up, because I get really intensely involved in that state.

SW: Have you always been that way?

AA: I’ve always been that way since I was a little kid. It’s that restlessness. I’m sort of anxious. It’s embarrassing a little bit. I just think much, much better with a lot happening. But it’s not just things happening. When you’re working very intensely on something, through physical motions, at some point you can see clearly and your hands continue working. There’s a moment of transcendence your brain allows you by needing all of your senses to keep what you’re doing accurately, and that lets other parts of your brain open up. And that’s the state I’m addicted to, and I look for things to reach it.

SW: What keeps you from reaching it?

AA: I mean often I’ll think really clearly in those moments when I’m halfway awake. But as soon as you wake, it changes, and it changes your ability to have a fluid way to see things. Like, you’ve told me that the right word came to you in the morning; morning is an interesting time.

SW: It is. And I think of writing as a sort of paralysis in which you only get to move once in a while, like occasionally wiggle a big toe or something.

AA: Writing is hard. I sent you some things that are not what I intended. That’s what I meant, that language is cursed to me.

SW: It’s hilarious, trust me. But do you think that maybe what you think is your private language is actually more deeply felt than you know? Is that a more terrifying thought than being misunderstood, that everybody gets you?

AA: I don’t know. I have a language. I have things that mean something to me. But I don’t necessarily think that my own sort of fears and desires are what anybody wants to know about. What they’re interested in is their own. And having a vehicle to find their own. There’s that poem you recommended [by Szymborska] where she’s trying to get inside the mind of the rock.

SW: Oh god, that poem is so great.

AA: And it’s kind of trying so intensely to get inside the world and understand what you can’t understand and still wanting to and still always attempting, always asking, over and over, to try to understand something that you’ll never understand. Not even close.

*

This conversation took place between Alma Allen and Su Wu. Allen’s first solo exhibition at Kasmin went on view at 509 West 27th Street between January 23 – March 4, 2020.

Allen’s 2020 monograph, published by Rizzoli Electa, features newly commissioned photography of Allen’s studios in Joshua Tree, California, and Tepoztlán, Mexico—two spaces designed and built by the artist. Texts by Glenn Adamson and Douglas Fogle illuminate Allen’s work, which is painstakingly made in foraged wood, sculpted marble, and cast bronze.