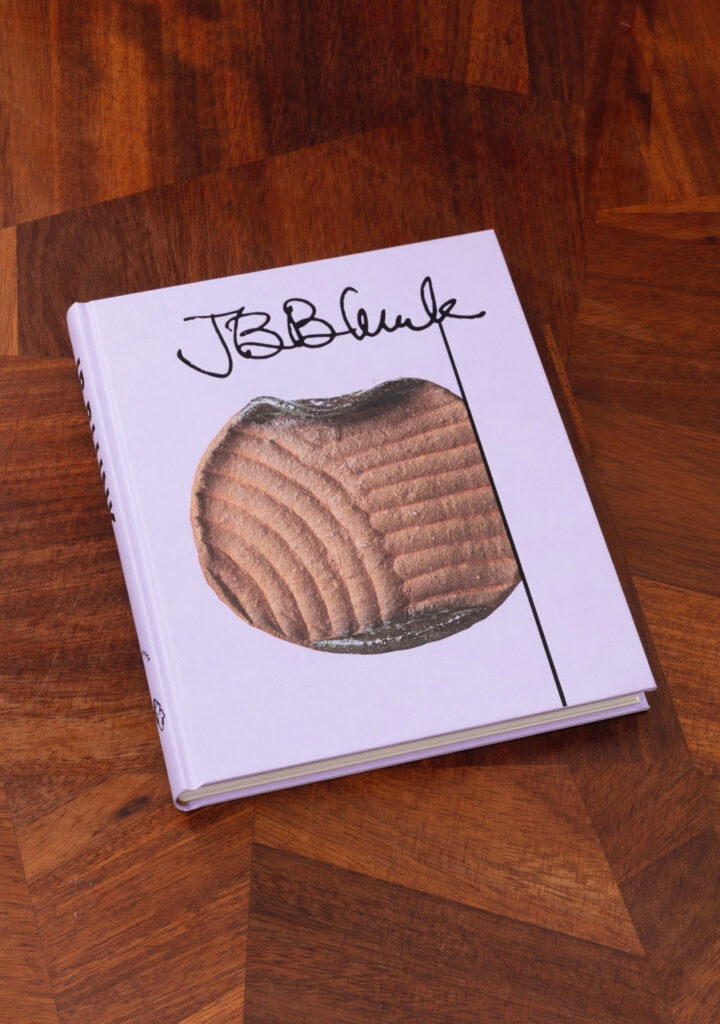

On occasional Saturday mornings, Kasmin shares essays and interviews from the gallery archives. The below conversation took place between JB Blunk (1926–2002) and Rita Lawrence and was held during the opening of the exhibition JB Blunk Sculptures, 1952–1977 at The Craft and Folk Art Museum, Los Angeles, 1978. The interview is now reprinted in the pages of the artist's newly published monograph JB Blunk. Blunk's first exhibition at Kasmin went on view at 297 Tenth Avenue in Winter 2020. Learn more in the accompanying online viewing room.

Rita Lawrence: Why did you choose Isamu Noguchi to write the introduction for your recent exhibit at The Craft and Folk Art Museum?

JB Blunk: Noguchi is the one artist who has been the most important motivation for me.

RL: Noguchi speaks of aiding your ‘finding of your way in art’. What did he mean by that?

JBB: He was much more aware of where I was going, of my search as an artist, than I was. There was a touch that occurred between us which has never stopped. It was one of those meetings that change your life. Everything that happens after that can relate back. They are always a part of the source. They return to the source and go out again. My meeting with him was one of those. It’s very identifiable, and not only as an artist but as a way of life.

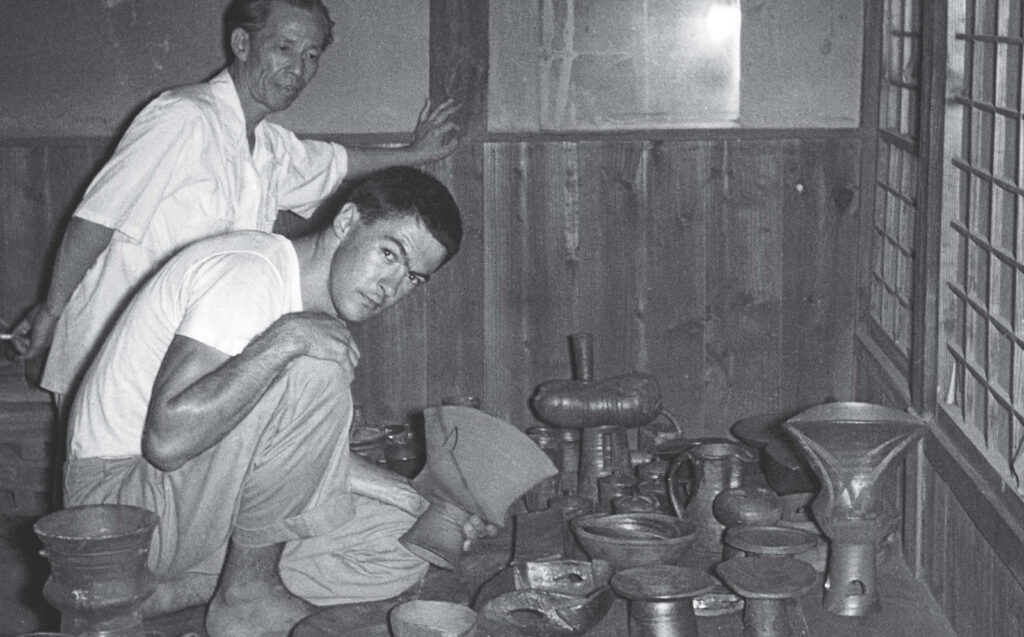

RL: Before going to Japan you were an art major at UCLA and Laura Andreson was your mentor in ceramics. You saw an exhibit of Japanese pottery that had a great influence on you.

JBB: When I walked into that Mingei exhibition at Scripps and saw those things, I decided right then that that was what I wanted to get into. It was one of those unconscious things where something really touches you and you want to find out more about it.

RL: What was the special quality of the Japanese work that appealed to you?

JBB: I think the words that express that are directness, purity, honesty, elemental.

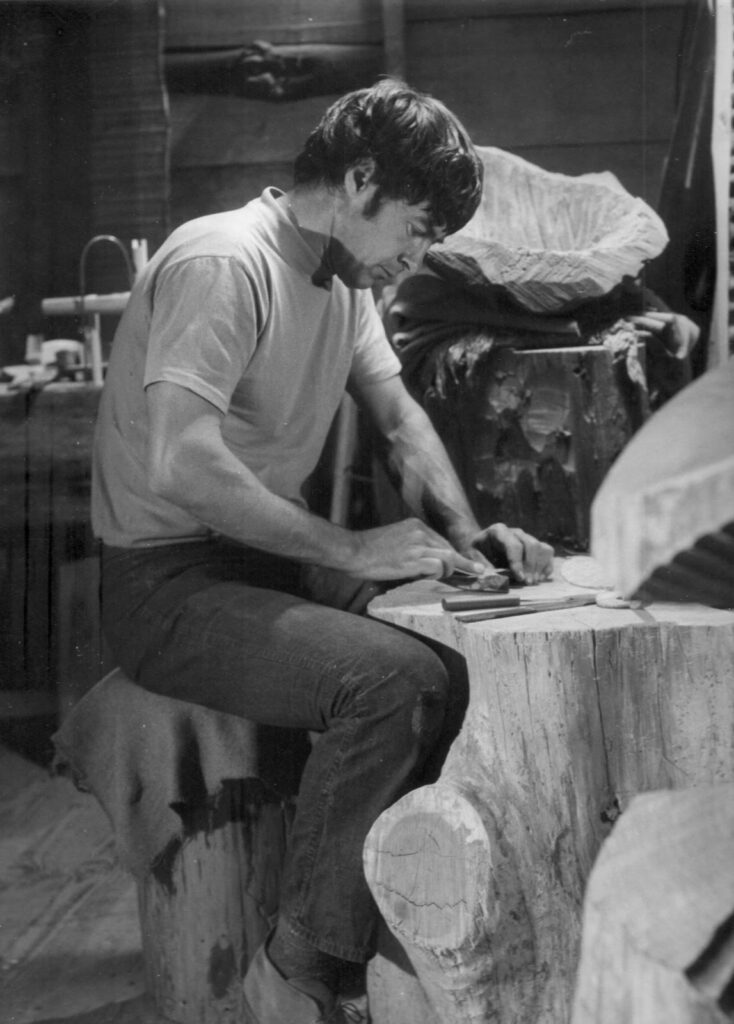

RL: When you worked with Rosanjin Kitaoji and Kaneshige Toyo you lived with the families, shared a Japanese potter’s existence. Did some of that influence more than your work?

JBB: Of course. It’s still with me. The way I think and relate to the place around me and the environment, ecology, had its inception then and was important in forming an idea of a way of life. But I had no plan. The building of the house, and all that came after, was the result of other experiences after I returned. I moved to Inverness to build a kiln and to make ceramics. I was afforded the opportunity of a place to live and work and, with all of my being, I was hoping to do that. At that time I was even so naïve as to think I would live and work in Japan!

“We’re bombarded with advertisements of things to make life easier, less work. But I think respect and love for work is part of life. Not only acceptance of work, but a joy, a meaningfulness in working as a process of life, that is close to godliness.”

RL: California Design has just published a book called Craftsman Lifestyle—The Gentle Revolution. You were so many years ahead in terms of what a whole generation of craftspeople have tried to do.

JBB: In many ways I was doing this a long time before other people. But there have been other people doing it better for millions of years.

RL: Most artists and/or craftspeople cannot really support themselves solely by their creative work and need to teach to supplement their incomes.

JBB: I have chosen not to teach even though the opportunity was afforded at a very early time in my career. I really believe in the apprenticeship system, the direct relationship from person to person which makes such a difference to us in our lives. That, I’m sure, has a lot to do with the fact that I’ve chosen to do other kinds of work, over the years, in order to sustain myself. I’m not putting down teaching. I’m just saying it’s not for me in that way. The teaching that I do is more directly with the people for whom I make a difference, at any age or at any time. I am just passing it down, passing it up, or along whichever direction you want to say.

RL: If you had your choice, would you prefer to do utilitarian objects over making more abstract statements in your sculpture?

JBB: I think you can answer that question by seeing the total output of my work. They’re both there. They happen, they occur, they are both part of my work interchangeably, back and forth all the time. It’s not something you can separate. In fact, I’m determined that they should not be separated. If you are making something that people sit in, it should at least be a little comfortable, right? And depending on where it’s used, the people who use it, and how much it’s used, you may have to compromise. Hopefully it won’t necessitate having to change the form to something you like less to make it more comfortable. The two should go together. But there have been commissions for pieces where I had to accept from the beginning the condition of a really high degree of comfort. I’ve made some benches that aren’t very comfortable, not as comfortable to sit in as others, but are very interesting sculptures. I think you will find that all through history, and in different cultures, what is comfortable to one is not necessarily comfortable to another. I think of comfort, in terms of, I guess, ease. We’re bombarded with advertisements of things to make life easier, less work. But I think respect and love for work is part of life. Not only acceptance of work, but a joy, a meaningfulness in working as a process of life, that is close to godliness. Now everyone doesn’t have to work in the same way. But there is a certain amount of relating to things with one’s body that our present civilization divorces us from.

RL: Are you making the existential statement that we are what we do, not what we think?

JBB: Some of us are doers. Some of us are dreamers. And some of us get mixed up in both. There are people who don’t do much physically but they bring people together, and ideas together, and make things happen. And sometimes there are frustrated doers. There is no one way.

JB Blunk, Untitled, 1975-1980, redwood, 16 x 17 x 14 1/2 inches, 40.6 x 43.2 x 36.8 cm.

Installation view of JB Blunk at Kasmin. October 8–November 7, 2020. Photo by Christopher Stach.

RL: Looking back, can you see certain themes in your work which, perhaps, you were not aware of at the time?

JBB: More just a sense of where I was at that time. The exhibit is a kind of completing of a cycle; really a putting together of these things and seeing and feeling that this is one of those points from which it will never again be the same.

RL: What makes that; your knowledge from looking back or the understanding of where you are at now?

JBB: This is an intuitive thing that happens as a result of the process. The process is the doing, the bringing together. It is something I wanted to do for quite a while, but wasn’t searching for the way and it just happened. And the process of doing it has meant a great deal to me, not only in the physical manifestation of it, but in the people I have met and the talks that have occurred and the feelings I have had as a part of the process. And now I have come to realize that it is the end of a cycle, signified, or objectified by the exhibit, and, therefore, once that has been done things won’t be the same again.

RL: What do you suppose will happen to you, then, if this signifies a leap into recognition.

JBB: I’m not thinking in terms of recognition or acceptance or that sort of thing. I’m thinking only in terms of being curious about myself. Some recognition may occur. I may sell some of the pieces and become able to do some other work that I want to do. But whatever does happen will be like another beginning. I think life is a series of beginnings, and the one who feels they are always a beginner is the one who has the best chance. Because we don’t do it, it happens through us. It happens to different people in different ways at different times. I don’t believe in the importance of ego, but at the same time, I really do believe that, regardless of what one does, when one surprises oneself, then that is the real juice of life. And it is for those surprises that I live.

RL: You have said it so many times. What do you mean by ‘it happens through us’?

JBB: When you’ve created something that makes a difference to someone, that juice, that energy, occurs through us. See, I think all the discoveries, all the essence is already in existence.

RL: Do you mean that in the Socratic concept that nothing is learned, everything is remembered?

JBB: In a way. Everything is already known. We just haven’t seen it yet, haven’t recognized it yet. And it doesn’t have anything to do with time.

RL: Cultural memory?

JBB: No, not just cultural memory. Everything already is. It’s just when we are open to being in touch with it, it seems then to happen through us.

RL: Are you saying it in a theological sense of the work of some supreme creator or being?

JBB: I’m not saying that someone is up there calling the shots. I’m saying it’s more omniscient, omnipresent than that. It doesn’t have words.

RL: Does the process of ‘happening through us’ include a re-living, or a re-knowing of a previous life?

JBB: Some people look at it that way, and I’m not sure that it’s not a valid way. There is an awful lot of information and an awful lot of experience that would make that hard to disbelieve. I am very curious about all that sort of thing and have been for many years.

“I don’t believe in the importance of ego, but at the same time, I really do believe that, regardless of what one does, when one surprises oneself, then that is the real juice of life. And it is for those surprises that I live.”

RL: Do you view your own artistic creativity in the Zen sense, as the freedom resulting from total mastery of craft, or as an extension of the mystical concept of creation, as something that you have known before?

JBB: Everything happens through a process such as working, such as meditating, such as running, such as being extremely exhausted or in an extreme state of ecstasy. It’s during that time that true creativity occurs. And then it seems to come from nowhere or from everywhere, and it is a surprise. I mean it seems to happen; not just in terms of artists or objects or whatever. It can be in terms of falling in love. People have numerous experiences, it would seem to me, not necessarily when they are seeking them but when they are in an open state. And there have been many, many ways during the time we have been on this planet, through history, of getting to that state. And now so many of those ways are available that were never there before, and it’s blowing people’s minds. There are probably as many ways as there are people. My way, so far, has been my work.

RL: Your way to ecstasy, to clarify, to giving of yourself, to what?

JBB: To consciousness. My way has been through my work in general, but I have ceased to believe that that in itself is the end-all of life for me or for anybody else.

JB Blunk,Figure/Odalisque, c. 1991-1996, redwood and river stone, 44 x 14 x 10 1/2 inches (overall), 111.8 x 35.6 x 26.7 cm.

RL: Rousseau says: ‘Men live not in order to live but to make others believe that they have lived.’

JBB: Right! Because they miss it. There comes a point where you just have to do it. I have never had this problem of philosophizing and then putting it into action. I have usually had it happen, even with my own work. I’ve learned about it, learned a lot about myself, from consciously going back and seeing what I’ve done. But that didn’t happen in my life for a long time because I was just doing. And then one day—FLASH—I started being conscious of what I had done, and once that starts, life changes. Now I am curious. I am wondering what is going to happen. For some time I thought I knew exactly where I was going and what I had to do and I was really focused. I was very unconscious of even what I was making. Things, ideas, were just pouring out. I am not in that state anymore. It’s a very different way of living, and it’s sure not as easy. I am both feeling better about what I have done and what I am doing and at the same time open to what else might happen—and it may not even be sculpture. I am more open. Open to the life process—to being, not just doing. I am trying to be open to a new way of being in the world.