On occasional Saturday mornings, Kasmin shares texts that expand critically on the work and practice of the gallery artists. This interview with Elliott Puckette, led by Judith Goldman, was commissioned to mark the artist's 2008 exhibition at the gallery. It remains an excellent reference on the artist, who in 2022 debuted her sculpture alongside new paintings. Explore the online viewing room here.

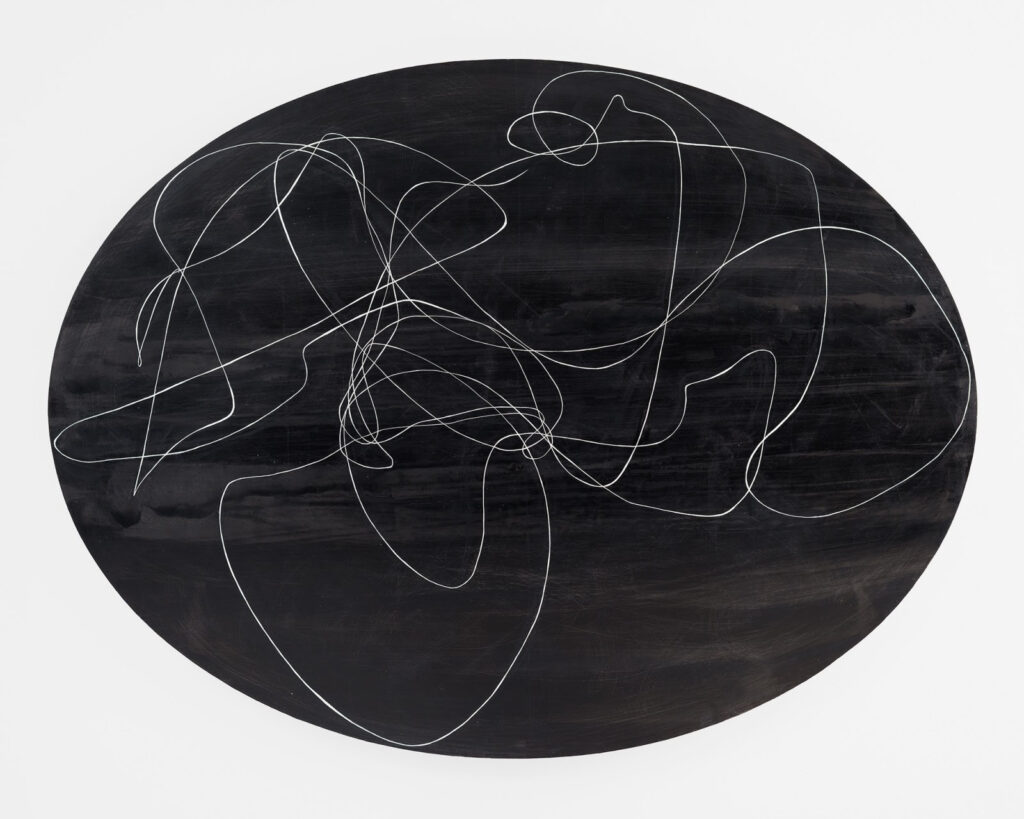

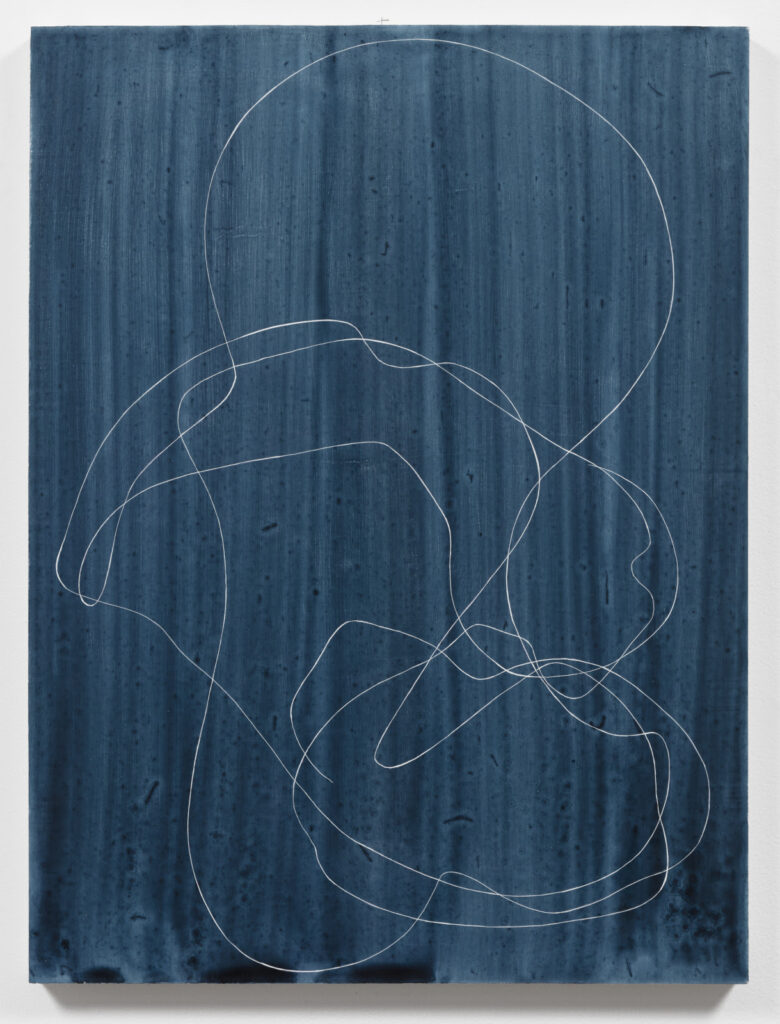

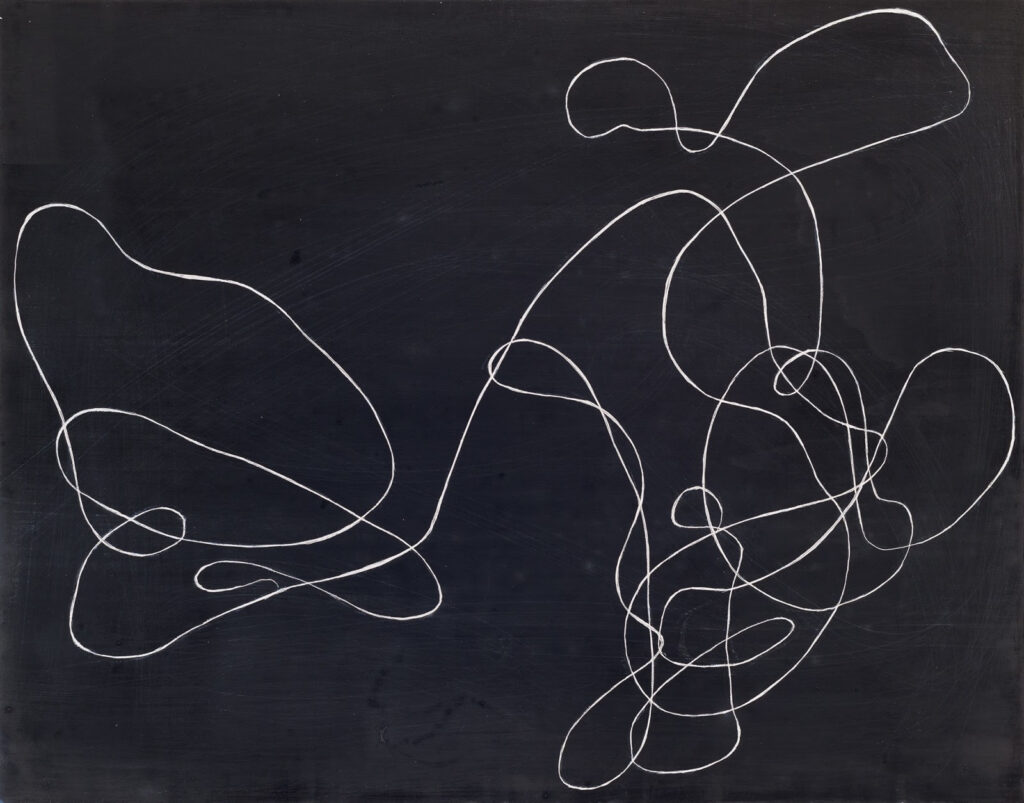

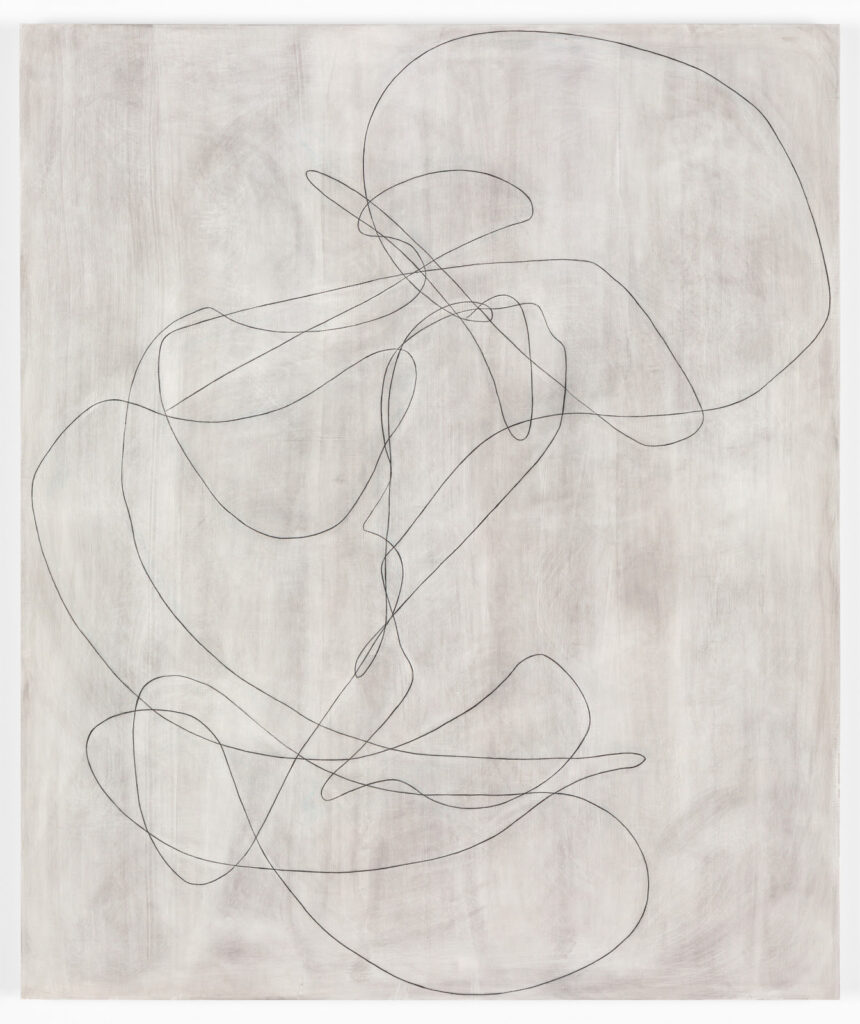

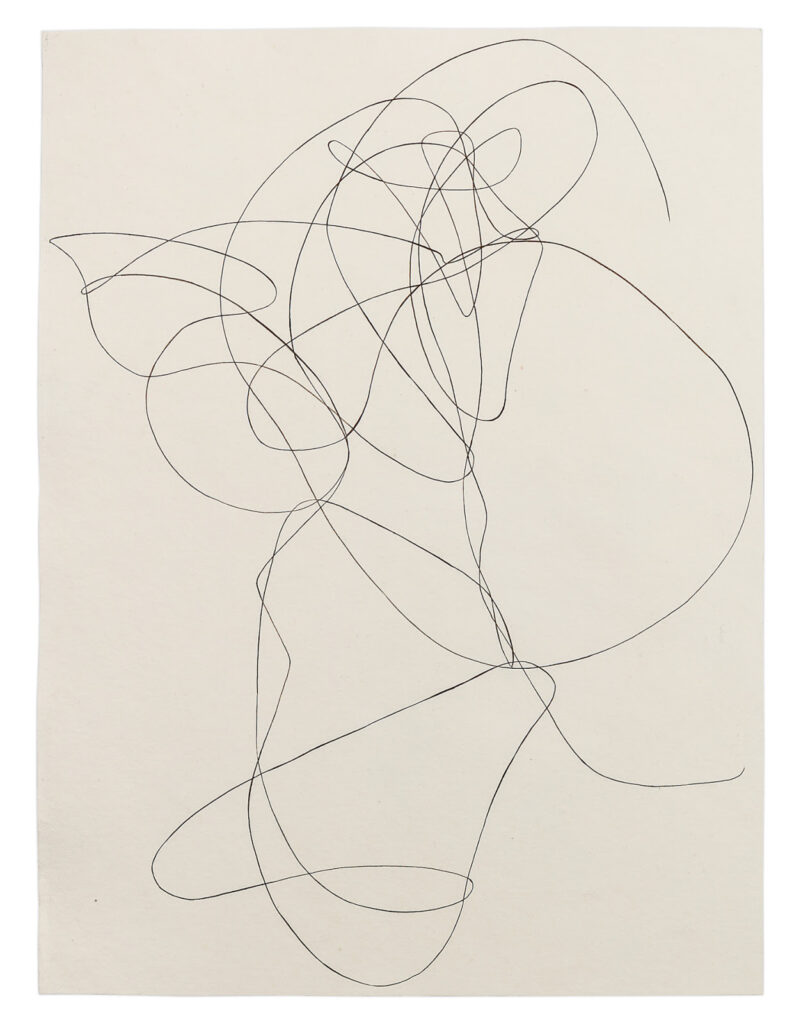

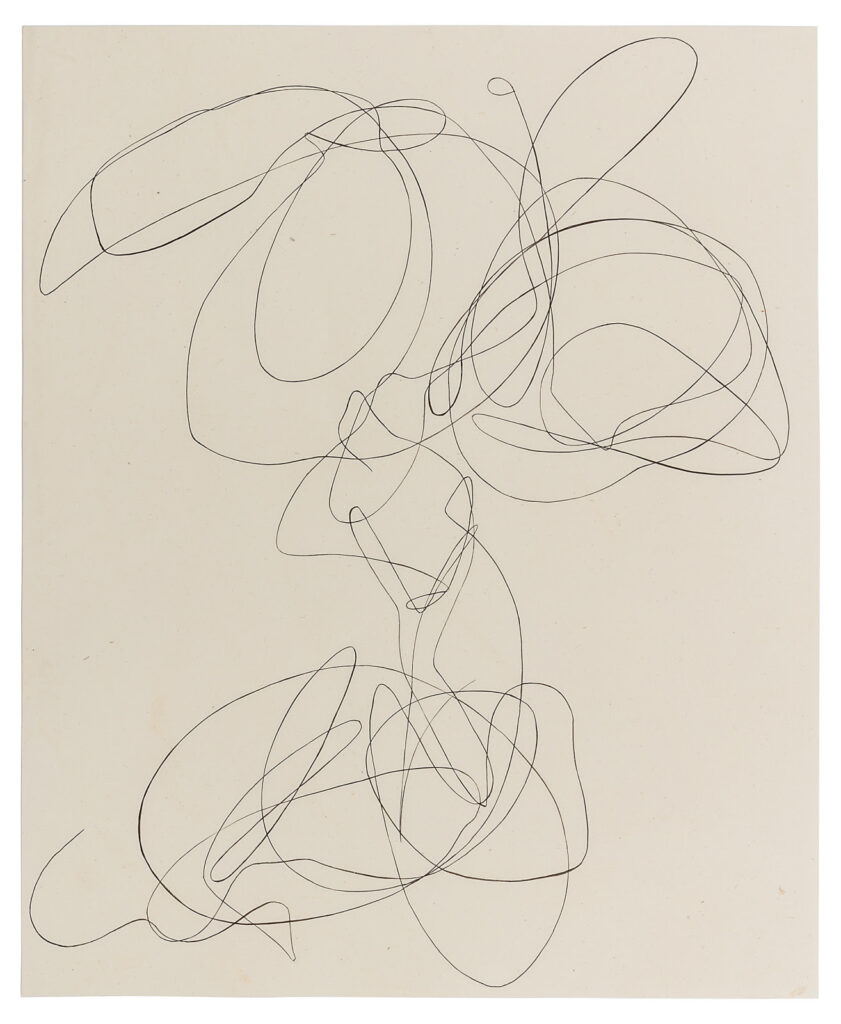

Since her first New York exhibition in 1993, Elliott Puckette has been creating abstract paintings out of an array of calligraphic lines. She cites Constable’s skies and Tiepolo’s drawings as inspiration, and her decorative sources include: Arabic calligraphy, ornamental letters, elaborate scripts, and curlicues. The resulting lines are rigorous and wild; they scroll, billow and glide; moving continuously, they lollygag about and do everything but stand still. Even at their most baroque, the elegant simplicity of a Puckette line belies its complex process. She literally incises lines; cutting with a razor, she digs and scratches them into the gesso-covered surface of her paintings.

Our interview took place on two mornings in December of 2007 at the Paul Kasmin Gallery in New York City. Puckette and I sat at a small table in the middle of a downstairs viewing room. I had a tape recorder but forgot the microphone; she brought a breakfast of brioche and chocolate croissants that she’d picked up at a bakery near her studio along with books on Henri Michaux and Dick Higgins to help explain her influences and interests. Soon after we sat down, an art handler came to hang Puckette’s paintings on the walls around us. The pictures had just arrived, and it was the first time she had seen them since they left her studio. Preoccupied by her paintings, she’d turn her head and steal a glance at a painting from various angles. As we were about to begin, she abruptly got up from the table and, moving to a painting on a far wall, began sanding its surface. “It’s so hard,” she said, smiling, “to let anything go.” At another point, looking toward her pictures, she said “I guess I must be a modernist worrying so about a line.”

Born in Lexington, Kentucky in 1967, Puckette arrived in New York to attend art school in 1986. Twenty-two years later, traces of her southern upbringing remain evident. She has a soft, languorous voice and speaks with a slight drawl in meandering cadences. Tall, blonde and uncommonly pretty, she is naturally reserved and has the kind of old-fashioned manner that does not call attention to itself.

“There is something insane about agonizing over the placement of a line. So when I started making continuous line paintings. I treated it like a game. I’d find the beginning in the end, like a snake biting its tail.”

When did you first think about becoming an artist?

When I was fourteen. Until then I was an aspiring bag lady and had no ambition whatsoever. Then in high school, I had this wonderful teacher Rosie Paschall. She had gone to St. Martin’s in London and ended up in Tennessee, married to a professor at the University. She was very magnetic and brought so much life to the idea of art as only a great teacher can. She could emulate David Hockney’s line drawings. She could draw without lifting her pencil from the paper and without looking down. Before that, when I was younger, I was an avid reader and wanted to be a writer. I wrote long, rambling melodramas. My father encouraged my writing, but I think it’s safe to say that I did the right thing by not writing.

What were your other interests?

I was very into nature. I was an animist. I’d walk around the woods and look at the branches and trees and commune with nature. I remember sitting on outcroppings of rocks and looking up at the cloud format ions and at the bare branches of trees in the winter sky.

Did you grow up in the country?

In Sewanee, Tennessee. It’s a tiny university town on a mountain top, of about 2,000 people, most of whom were connected to the University of the South where my father taught mathematics and was the dean. He had family ties to the town. His great-grandfather, Bishop Elliott, was one of the University’s three founders. I was a faculty brat. I went to a school called St. Andrews. It was originally a small school for mountain boys who otherwise wouldn’t have gotten an education and later it turned into a co-ed school. There were day students and boarding students. In my day, if you were a boarding student who ended up on the mountain, it was one step away from being in a reform school, and it meant you’d been kicked out of every high school in the area. It was a fractured student body — local mountain kids, faculty kids and boarders.

lt was Rosie Paschall that inspired your interest in art?

Yes. As soon as I met her, that was it. She became my mentor. And in 1986, I came to New York to go to Cooper Union and never left.

By then, you knew you wanted to be a painter?

Yes. But I was an arrogant teenager. I thought I knew what I was doing and what I wanted to do. Actually, I had a lot to learn. I had to be humbled by the Bauhaus. Cooper Union had wonderful teachers. Giovanni Vanni taught us about the materials of the Old Masters. So that we really got a feeling for them, he had us make Damar Varnish and egg tempera, even frescoes. We also learned Bauhaus theory, color theory, architecture and had to do 2D Design, which cured me of ever wanting to do graphic design, not that I ever entertained ideas about being a graphic designer. But it was a good foundation course and very humbling and it gave me a great appreciation of architecture because it’s the antithesis of 2D. I also studied with Jack Barth, Rob Storr, and Gabe Gleason who taught printmaking. She was wonderful but I was absolutely useless at printmaking.

How long did you study printmaking?

Until I dropped a litho stone on my foot.

When did your fascination with line begin?

During my third year at Cooper. Before that, I definitely went in all sorts of directions. I did a lot of paintings of rebuses, puzzles, and dominoes. I’d copy rebuses from old books and add color. I approached abstract painting as if it were a game. I was interested in systems as a way of setting limitations so that you’d know when a work was finished. There is something insane about agonizing over the placement of a line. So when I started making continuous line paintings. I treated it like a game. I’d find the beginning in the end, like a snake biting its tail.

I also did needlework, I loved the meditative quality of it, and it suited my obsessive/compulsive nature. I’d been looking at a lot of Robert Ryman paintings and I made white needlepoints, monochromes, that went from dark to light. They didn’t exactly change colors but, during the time I worked on them, they became grubby from being touched and took on a kind of patina. After that, I did alphabets; I did Rimbaud’s poem “Voyelles” in needlepoint and I looked at scripts, wrought iron work and a lot of historical decorative art. Ernst Gombrich was a big influence, so was Oleg Grabar, the great authority on Islamic Art who championed the idea that ornament could be its own subject without referring to anything else. I was also very into French literature—Verlaine and Rimbaud, and I read a lot of Flaubert and Balzac. At the time, my interests were regarded as decadent because I was interested in objects. I would have been much more accepted if I’d been involved with theory, conceptualism, and video art. I just couldn’t do it. I didn’t have it in me.

Was the teaching of conceptualism that dominant?

It was huge, really suffocating and relentless. It was everywhere. There wasn’t much choice. One couldn’t take pleasure in what one did. Hedonism was not allowed. Art was theory oriented. Everything was problematic. To even pick up a pen — forget about it. What is it going to mean if I put pen to paper? You’d dissect your work before you even started. People read Robbe-Grillet, Lacan, and Derrida and it paralyzed so many of my friends. They completely bought into it and couldn’t make anything. I tried to read all the theory and to plug it into my own thing, but it was forced and very unnatural.

I see a visual relationship between the way mathematical signs and equations fall on a page and the look of your line.

l really don’t see that relationship; I am creating a problem of my own and trying to fix it. I remember once looking over my brother’s shoulder as he was writing a longhand equation. It looked as if he were writing a letter and reminded me of being a small child, trying to copy my mother’s longhand. It was incomprehensible, yet its form was beautiful, and it looked as if it felt really good to do. I wanted to emulate the form. I remember as a very young child scribbling madly while creating a narrative in my head.

Your sister is a mathematician. It’s interesting that your entire family is involved with aspects of time and space.

My sister’s dissertation was on random walks, and the infinite number of directions a line can take. It’s funny that the idea of a random line going for a random walk is the place where our interests intersect.

One could describe the lines in your paintings as going on random walks?

Yes. Exactly. I like to look at it that way. A line going for a walk — or a snake biting its tail — then it becomes complete.

Does your line relate to music as well?

I love music — classical, early jazz, Jimi Hendrix. My father was a real enthusiast. He played the mandolin and loved all sorts of music, and my brother Miller always had an ear and could pick out a tune. He composes computer music which is very mathematical and my other brother Charles is in a bluegrass band.

How did your interest in calligraphy and graphology develop?

I was looking at Victorian crafts, like stitching, and I went from the stitch to the word to the letter and then I wanted to translate it into a line although I don’t remember the exact sequence. Eventually I started looking at books on graphology and handwriting interpretation and at silhouettes by the 18th-century French artist Lavater which were meant to reflect a subject’s true character. Graphology is not that different from silhouettes. If you follow the outline of a silhouette it’s similar to a handwritten line.

What was your work like when you finished Cooper Union?

For a while, I did palimpsest drawings, lines over lines that also related to graphology and script. They were based on old family letters, written during the Civil War, when there was so little paper that people would actually write one way on a piece of paper and then turn the paper around 90 degrees and write the other. My family had a number of these letters and I was fascinated by them. Then I started taking images — a line or cartouche — from The History of Ornament and would add and flip them to make the image more complicated. I hadn’t arrived at my own free form line yet. I was still taking images from other sources and manipulating them. But when I was just out of art school, I got turned on to Henri Michaux and then came the dawn.

“I am always trying to figure out how to make a line resonate, how to make it emphatic and permanent. I’ve looked at a lot of Italian Renaissance calligraphy and Arabic calligraphy and all sorts of scripts.”

You’ve described discovering Henri Michaux as a eureka moment. What drew you to him?

I was poking around the surrealists. I liked the surrealist attitude — the theory, the automatic writing, the exquisite corpse. The look of surrealism didn’t really appeal to me, but I liked the fact that it gave one permission to do whatever one wanted. Michaux was influenced by Klee and the surrealists. His early work from the 1920s was very scratchy, then in the ’40s, he blew it up and started to create a language of his own. He did imaginary alphabets and I liked that they didn’t have any ascribed meaning. They were beyond words and entirely about the energy. He was all about getting lost in the movement of the thing. Michaux was also a very eloquent writer, like Richard Tuttle whose ideas also interest me. I’ve saved this article from The New York Times that quotes Tuttle: “The line is the place in the work that’s most indefinite, and it’s always the place that’s indefinite or not known that is the source of the art.” I like that sort of elliptical thinking, digressions of digressions, like the meandering rhythm of southern literature and the writings of T. R. Pearson and Faulkner.

Have you made linoleum cuts?

I did a bit in art school and in high school. I liked carving the linoleum but the process of printing was a nightmare.

It’s so interesting — you’ve applied the process of carving a linocut to create the lines in your paintings.

Yes, and I got rid of the rest.

If it were a drawn line or a painted line it would have a different effect.

Yes it’s thin and then thick. I am always trying to figure out how to make a line resonate, how to make it emphatic and permanent. I’ve looked at a lot of Italian Renaissance calligraphy and Arabic calligraphy and all sorts of scripts. I have fantastic books on the history of scripts and alphabets. I could study them all day. I’ve looked at illuminated manuscripts too, but there was always something fussy about them. Aesthetically I didn’t gravitate toward them. I was much more drawn to the Cabala and celestial alphabets.

Who influenced you?

Bruce Connor was an influence and Lucio Fontana. And so were a lot of 1950’s filmmakers like Stan Brackage and Lin Lye who did scratchings on film and made beautiful abstract films. I love James Nares’ work. We share an interest in calligraphy. And I was fascinated by the threshold paintings I saw in southern India. Early in the morning, women come out, wet the soil in front of their doorstep and make paintings with chalk, in a continuous line drawing. The paintings are called Walums, and they’re meant to ward off the evil spirits who want to enter the house. They get caught in the symmetry and can’t get out. Something about symmetry keeps the demons at bay.

Like a maze?

Yes. I’ve read a lot about the history of labyrinths. Getting lost in a labyrinth is about erasing oneself. You’re part of the process, in the groove and in focus. It’s not a bad place to be.