On occasional Saturday mornings, Kasmin shares essays and interviews that expand critically on the work and practice of the gallery's artists. This essay, Paint Calling to Brush, Sea to Sky by Erin Kimmel, is published by The Kasmin Review on the occasion of our current exhibition Jane Freilicher: Abstractions. In this text, Kimmel maps an incisive topography of a time in Jane Freilicher's life and painting career in which the artist frequently made visits to Water Mill, Long Island from New York City. The series of works made during this time marks a crucial moment of discovery and focus for the artist, who went on to integrate the freedom, fluidity, and confidence developed during this period into her more recognizable still lifes and landscapes of later decades.

Flying Point Road winds its way gently south out of the once small hamlet of Water Mill, Long Island, turns east hugging the south shore of Burnett Creek and bends south to the shore of Mecox Bay before making a straight shot to the scrubby dunes, blanketing white sand, and crashing waves of the Atlantic Ocean at Flying Point Beach. Beginning in 1957, Jane Freilicher and her husband Joe Hazan, as well as the painter Jane Wilson and her husband John Gruen, rented a house perched right before the bend on Flying Point Road overlooking the large flat Mecox Bay. An oblique aerial photograph taken of nearby Georgica Pond in 1947 for survey purposes by the New York office of Fairchild Aerial Surveys offers a sweeping view of the land-use patterns that characterized the area during that period (fig. 1).[1] Despite Water Mill’s burgeoning postwar popularity, it shows that most of the land was agricultural—straight lines jut out from the craggy coastline forming geometrical plots of harvested land that contrast with the dark, expansive, and organically shaped lagoon.

It was here in a patchwork of sea, sand, scrub, town, and farmland that Freilicher transitioned out of a mode of living and painting that had defined her life and career until then. In the previous five years, she had established a reputation for herself as a painter of intimate urban and domestic surrounds. Her canvases pictured interior scenes of her modest East Village apartment and makeshift studio, the skyline view out of the window of that apartment, and her friends and colleagues in various states of pose and repose there. Her canvases were painted in a lush yet somehow restrained manner—Frank O’Hara lovingly referred to them as “radiant,” “gentle” and “unassuming” in a 1954 review—merging traditional compositions and controlled brushwork that refused to hide itself with the lyrical use of faded color.[2] The result was a unique emotional tenor at once calm and enigmatically whimsical, a combination that invited comparisons to her personality by the poet and artist reviewers that were her close friends.[3] But, in 1957, she dispensed with this well-practiced mode for something different, something looser and less quiet.

“Now in the last few months, I no longer want a subject to begin with,” she told John Ashbery in an interview, “it seems that the very paint itself will suggest some sort of image.”[4] Turning away from the concrete subject matter—her apartment, her friends, the city skyline she had professed to be wholly committed to only a year earlier—her canvases transmuted into swimmy, luminous investigations of visual and pictorial memory. “I guess it tends toward abstraction,” she continued to explain to Ashbery, “which I felt I was very far away from, though I feel it has some sort of natural foundation, as if I were painting the underside of the earth, something growing beneath the surface.”[5] Freilicher’s new mode of painting, as well as living, certainly echoes the double liminality of a bubbling up of something from below, something in-between. The years represented in Kasmin’s exhibition Abstractions, 1958 to 1962, were transitional for the artist. And thus, they were many things: a farewell to the rowdy, artistic comradery of her twenties; an embrace of a romantic and domestic partnership that would last for the rest of her life; and, most importantly, the new spot on the earth’s crust—a road running along a spit of land surrounded by all manner of water that induced an extraordinary change in her approach to painting.

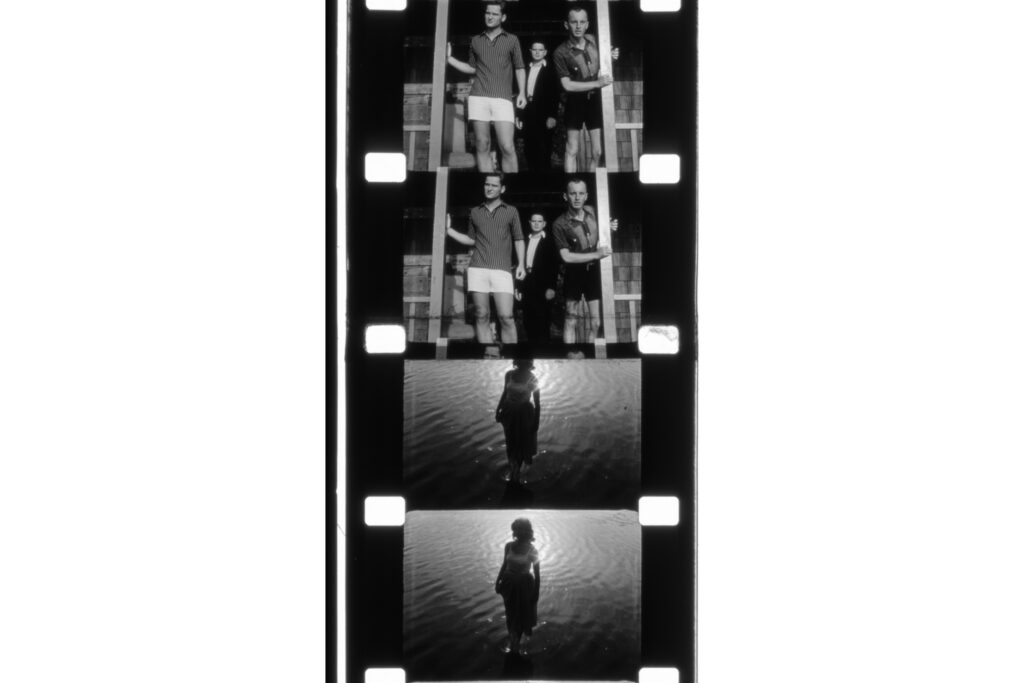

Prior to 1957, Freilicher’s time on the South Fork of Long Island was characterized by short trips with her cohort of poets to escape the city and visit friends such as Anne and Fairfield Porter at their rambling Southampton house. In the summer of 1952, they convened in East Hampton with the now famous quartet of poets John Ashbery, Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch, and James Schuyler, to shoot a mock-noir short film “Presenting Jane.” Scripted by Schuyler, the comedic short eulogized Freilicher’s revered place within the energetic and erudite crew. Frames from the recently rediscovered reel reveal a cut between two distinct scenes (fig. 2). In the first, a perplexed Ashbery and a rapt O’Hara peer confusedly off the front porch while a broody Schuyler stands behind them, staring down the camera. The frame then shifts to a shot of Freilicher made to look like she is walking on water. Backlit by the sun, she emerges from the shimmering bay with arms extended in a Botticelli-like manner and flanked by two rays of sun. The still’s languidness and evanescence become a potent augury of the direction her painting would take once she began to spend extended periods in the watery landscape.

By that time, the comfort and tight-knit comradery of the group of twenty-somethings was fractured by the unfolding of personal quests and careers. O’Hara left for a stint as a resident of the Poets’ Theatre in Cambridge in 1956, one year after Koch and Ashbery, arguably the painter’s closest friend, left for Paris. Meanwhile, Freilicher doubled down on her allegiance to the local—marrying the former dancer, now family businessman Joe Hazan and moving into a townhouse at 16 West 11th Street while spending summers on the East End. It was, perhaps, a physical expansion and emotional consolidation of her life. The Mallow Gatherers (1958, fig. 3) is a brushy rendition of the view from the rental house over Mecox Bay that Freilicher exhibited at Tibor de Nagy Gallery in 1958. On the distant horizon, a few black strokes suggest a rickety colonial house and barn, while dense patches of green and black scribble compose the contours of coastal thickets. A copse of reedy, colorful marsh grass made of swift, feathery upward strokes dominates the foreground and faded azure waters, achieved through the inter-application of copious white, surround it. This painting is key to understanding the paintings to come as it pictures the view of Mecox Bay in rather classical terms. It was this view, which she conjured, dissected, and mapped from her New York studio for the next four years, in such ravishing paintings as Near the Sea (1959–60, fig. 5), in which a reef composed of patches of rich blues and greens hovers horizontally in the foreground while a sweeping vertical stroke of seafoam bisects it.

193 × 195.6 cm. Private Collection.

The Mallow Gatherers was exhibited at Tibor de Nagy in March 1958. In a review of the show, Lawrence Campbell announced that Freilicher “was, until not long ago, addicted to painting directly from her models. Now she looks and remembers afterwards or invents ideal interpretations of scented and mysterious indoors, or looks only a little and not often out of the window at fields.”[6] View Toward Mecox Bay (1958, fig. 4) presents a nearly identical view presumably out the same window with colors found in The Mallow Gatherers. However, Freilicher has eliminated depth, flattening the composition into creamy swaths of color to represent the variegated land that separates the glowing sky and placid bay into a swirl of washes that she then hangs on the surface of the picture plane. In both, she continues to paint with thick paint and dryish brush, staying in line with her previous style which invited comparisons to Matisse by reviewers and reminds me equally of Bonnard and Vuillard.

Consider View Toward Mecox Bay alongside Small Harvest Moon (1958). The latter is a small painting, almost a study. In it, Freilicher thins her paint and lets the color come apart. Geometric washes of yellow, green, blue, red, purple, and pink, three of each, are suspended atop a swimmy white background. Two thick curvilinear strokes of black trace the outside of a marigold circle that suggests a sun while a straight horizontal line in the middle ground highlights the vista separating water and sky. Three red squares echo the wispy red strokes that play across View Toward Mecox Bay. Freilicher’s sparse use of painted black line makes the painting cartoony. Nevertheless, the surface is unified and enlivened by the tripartite play of colors across the central axis of the canvas. A translucent cloud of canary yellow hovers right above the horizon dripping down into the pink wash below it. It’s a beautiful drippy moment that initially reminded me of a sunspot until I remembered Freilicher’s titular reference to a harvest moon, which appears red when viewed from the horizon and through the full thickness of atmosphere, which absorbs blue light and transmits red.

Harvest Moon (fig. 6), also from 1958, is a floatier, more ethereal enlargement of Small Harvest Moon. In it, Freilicher narrows the width of her black contour lines and adds a few extra that tuck a portion of the marigold moon behind a cloud, extend the tilted horizon west, and underline the moon’s reflection in the water below it. She adds heft to the stains, washes, and drips by building and blending lighter tonal blotches, often gray, around them—endowing them with shifty shadows. She seems to be experimenting with how far she can let the compositional elements drift apart while retaining its pseudotraditional legibility as a landscape. Once again, the interplay of colored marks captures the glistening movement of light over water. The longer one looks at this body of work from 1958, the clearer it becomes that Freilicher is training her brush and mind in the analysis of the physics of sea-brewed light raking across Mecox Bay.

Nowhere is this clearer than in Untitled (Mecox Bay and Field) (c. 1958). Among the most intriguing of the paintings in the exhibition, it might be read as a study or series of polychromatic graphs demonstrating reflection and refraction. Once again, Freilicher has delineated a tilted horizon in the center of the canvas, this time through discordant mixture of painterly elements: magenta, forest green, and marigold sweeps; anxious little vertical brushstrokes; and soft reefs of blue, gray, and green. On the left-hand side, a strong vertical force made up of similarly varied marks interrupts the horizon, fracturing the picture into four distinct planes, which then continue to crack into a wobbly planar checkerboard. Freilicher’s use of scumbles—extraordinarily thin washes of paint—feels somehow hewn or etched into the canvas to make the checkerboard demonstrate her interest in conjuring every variety of reflection, glare, and shadow. They also recall the otherworldly sensory perception of Sam Francis who, like Freilicher, mastered the liquid and transparent effects of dry brush scumbling, a technique achieved by diluting paint with turpentine and combining wet on dry layers. In Untitled (Red and Green) (c. 1958) she loosens the geometry of the patchwork, letting the paint’s fluidity speak to the landscape in soft seductive terms. The architectural historian Alastair Gordon has compared the historical appeal of the Hamptons to that of a blank sheet of paper. He writes, “A landscape of extremes, it nevertheless has a neutral, passive quality that outsiders tend to read in their own willful ways.”[7] The expansive white and beige planes of her canvases translate the flat open patchwork of briny marshes, quiet bays, cresting sand dunes, meadows of scrub and pine and fields of potatoes as iridescent light rakes over the varied seascape.

By the end of 1958, James Schuyler penned in a review of a second exhibition that year that Freilicher “in her radiant new show comes close to bypassing the image all-together in her love of paint calling to brush.”[8] Freilicher’s paintings from 1958 blend the analytic and the romantic, repeatedly honing in on a defining feature of the South Fork: its extreme horizontality, so pronounced that virtually any vertical, whether a telephone pole or ray of light, is enhanced by its intersection with the horizon. This is especially true of Flying Point Road as it extends along the lengthy and level south shore of Mecox Bay to the ocean. Once again, another more realistic painting, Flying Point Road (1959), provides a hint to decoding the paintings in Abstractions by capturing the drama of one of these intersections. Against a luminous creamy white background, the strong grey, green, and black verticals topped by the slashing vertical of a telephone pole rises forcefully from a wooly horizon. Below, tufts of green, yellow, and grey strokes denote a field. Painted wet on wet and by turns crisp and mushy, it evokes a view shrouded in haze or a light storm. This same misty out-of-focus quality permeates Untitled (Near the Cove) (c. 1958, fig. 7), which immediately invites comparison to Paul Cézanne’s serial studies of Mont Sainte-Victoire. Energy moves down and out of the giant vertical veridian slash, discharging almost like a waterfall, while a colorful scumble of drips, pours, washes, and wipes denotes a zig-zagging distance.

Freilicher describes the paintings exhibited in her February 1960 Tibor de Nagy show in a letter to Ashbery as “abstract but organized on landscape ideas and shall we say quite luminous in color.”[9] Freilicher’s transition to landscape-inspired abstractions brings her into a three-decade critical discourse that wrestled the relationship between western abstraction and the natural environment, one that had taken on increased urgency in the postwar years. “Due to the ferocity of modern life, man and nature have become one,” Frank O’Hara announced in a catalogue essay for a 1954 exhibition at Tibor de Nagy entitled Nature and the New Painting, in which Freilicher’s earlier work was included. O’Hara’s declaration is a tacit reference to the atomic bomb’s perceived shattering of the separation between the human realm and the natural realm, which he argues moves abstraction’s engagement with nature away from the metaphorical towards the staggeringly personal. “Here the painter utilizes his visual experience for subject matter,” he says, “but his experience is the subject, nature is not, and therefore the structure we observe is that of his experience rather than of what he has experienced.”[10] A host of other curators, art writers, and critics were exploring this shift—all similarly concluding that the relationship between abstraction and nature had become a matter of sensory perception—the strive to establish some perceptual universality between a surface or outer reality and a personal inner reality.[11]

In other words, discourses around so-called “second-generation” Abstract Expressionism turned on embodiment, the intimate relationship between an artist’s physicality and the broader, often natural, world. We have no record of Freilicher’s feelings on this, but in the same letter to Ashbery, she evokes her painting’s relationship to the weather: “…the pictures all look very transparent, evanescent, etc.,” she says, “making one conscious of the weather and how cold it is in New York in February which will probably make people decide to invest heavily in furs rather than my paintings.”[12] Rain (1958) and Untitled (Winter Sun) (1960, fig. 8) bring forth the cutting chill of coastal drizzle and the icy iridescence and strange glow of the beach in winter, contrasting with the blinding brightness of hot sun and sand punctuated by the primary colors of much beach paraphernalia evoked by Summer Landscape (1959).

By layering brushstrokes into a thick halo of clouds of optical white over the already layered creamy off-whites on top of unprimed canvas, Freilicher transmutes the quiet radiance and texture of a winter scene or the heat and glare of summer. Her use of white echoes that of both Willem de Kooning and Joan Mitchell, who were working in the same vein: employing the absence of color and the paint’s materiality to evoke unbounded space. White was key to De Kooning’s extravagant distortions of space in his heavily worked and jigsaw planed paintings sometimes referred to as urban expressionism from the mid-1940s, which featured dense webs of white shapes woven with black lines. It remained an important tool throughout his infamous Woman series; white accents helped him press the image up against the painting’s surface. By the mid-1950s, De Kooning, like Freilicher, had turned most of his painterly attention to the experience of transit between Long Island and New York City. “They’re emotions, most of them, the later ones. Most of them are landscapes and highways and sensations of that, outside the city. With the feeling of going to the city or coming from it,” he explained in a 1960 interview.[13] In Door to the River (1960, fig. 9), broad brushstrokes of bright white, canary yellow, rosy pink, muddy brown and sapphire blue are stacked and fanned. A series of wet, rectangular white-blended strokes at the center of the canvas evoke a door underneath which lies a passage of blue that suggests a flat ocean.

De Kooning, who is often cited alongside Arshile Gorky as the forebearer of the nature-abstraction nexus, was notably vocal in his support of Freilicher’s 1960 exhibition at Tibor de Nagy.[14] Montego Bay’s (1959–61, fig. 11) energetic and colorful buildup of an impasto shoal—more aggressive and grittier than many of her other paintings from this period—show her experimenting with lessons in white imparted by De Kooning. It also recalls the dense, frenetically architectonic structures woven with white that at once open out and recess in Joan Mitchell’s landscape-based abstractions such as Hudson River Day Line (1955, fig. 10) and Harbor December (1956). The latter was exhibited at the Arts Council of Great Britain’s 1958 exhibition Abstract Impressionism, one of the shows that aimed to untangle the nature of embodiment in abstraction of the period. As Katy Siegel has described, Mitchell’s paintings “use paint’s materiality to realize the feel of coursing water, making common cause of abstraction and representation.”[15] Any of Freilicher’s paintings from this period may be described in the same way, but instead of swerving and swelling like Mitchell’s mad tempests, they tend to flow: conflating surface and depth, flirting with linear perspective by locating the near and far, below and above the horizon with ethereal liquid washes and scratchy dry pats.

One year after she painted her first canvas entitled Flying Point Road (1959), Freilicher and Hazan settled on the very way, purchasing a plot of land surrounded by the bay, ponds, marshes, potato fields, sand, dunes, and sky. A photograph from the following year pictures Freilicher and Hazan standing in front of their new piece of land on Flying Point Road where the next year they would build a house. Behind them a field of thick, tall grass reaches back to the wide, low-slung horizon line that organizes so many of her paintings from this period and that stabilized the aqueous manner of painting which Schuyler described as “paint calling to brush,” and to which I’d like to add “sea calling to sky.” Another photograph from later that year pictures Freilicher wrapped in a rust-colored coat in front of the simple house and wrap around deck under construction, while two telephone poles lining Flying Point Road extend from the green horizon behind her (fig. 12). The house was completed in 1961, but her studio wouldn’t be finished for another year. By this time Freilicher begins a tilt back towards her previous mode of painting from life rather than memory—the barns, houses, tilled fields, telephone poles and grassy knolls surrounding Mecox Bay crispen into soft, lush focus in canvases such as Wide Landscape (1963) at the Whitney Museum of American Art. She continued to paint her Flying Point Road environs for the rest of her life, but never returned to abstractions as such. Instead, these paintings seem to have become a kind of groundwork for Freilicher’s later canvases, a part of her painterly habitus, a knowing of liquid light that undergirds the slippery abstraction that goes by the name reality.

Erin Kimmel is an art historian and art writer. She is a doctoral candidate at Stony Brook University where she specializes in 20th century art of America and the Atlantic with a particular focus on painting. Her research interests include the relationship between the politics of land-use and representations of land, Long Island history and the material, ecological and social histories of housing in coastal communities. Her dissertation traces the movement of painters to Long Island between 1920 and 1960, intertwining the landscape-inflected paintings they produced with the rise of the heritage, tourist and second-home industries. She has written for Artforum, Art in America and Frieze and served as the Associate Curator of Ballroom Marfa. She lives in Greenport, NY.

NOTES

[1] In aerial photographs of Mecox Bay taken in 1962 by Suffolk County for survey purposes and which show the house that Freilicher and Hazan rented in 1957-58 as well as that which they would build on Flying Point Road in 1961, the land use patterns remain strikingly like those in (fig. 1) taken in 1947.

[2] Frank O’Hara, “Reviews and Previews: Jane Freilicher,” ARTnews 53, no. 2 (April 1954): 45.

[3] As was typical, all reviews of Freilicher exhibitions before 1957 were written by men; less typical is that they were all Freilicher’s close friends who tended to see doubles in her work and read her paintings in the context of her personality. For example, in 1952, Fairfield Porter writes, “These paintings are broad and bright, considered without being fussy, thoughtful but never pedantic.” In 1953, Frank O’Hara writes, “Her sense of humor about her pictures is relaxed, maternal and appreciative,” while in 1954 he writes, “Light as radiant as it is personal…She seems not to struggle with the pictures, but to identify with them in a gentle, unassuming way…” It’s tempting to connect the clearly gendered language they used to describe her paintings to her lack of robust sales by Tibor de Nagy, especially in a period when critical success for a female painter was correlated to her ability to perform her public image as tough, sexually liberated, and unhindered by any domestic position.

[4] Jane Freilicher, interview with John Ashbery, c. 1958. Published as “In Conversation with John Ashbery,” in Jane Freilicher: ’50s New York, exh. cat. (New York: Paul Kasmin Gallery, 2018), n.p.

[5] Freilicher, interview with Ashbery, c. 1958.

[6] Lawrence Campbell, “Reviews: Jane Freilicher at Tibor de Nagy,” ARTnews 57, no. 1 (March 1958): 14.

[7] Alastair Gordon, Weekend Utopia: Modern Living in the Hamptons (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2001), 7.

[8] James Schuyler, “Reviews: Jane Freilicher,” ARTnews 57, no. 7 (November 1958): 13.

[9] Jane Freilicher, letter to John Ashbery, dated February 26, 1960. John Ashbery papers, MS Am 3189, Box 118. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

[10] Frank O’Hara, Nature and the New Painting, exh. cat. (New York: Tibor de Nagy Gallery, 1954), n.p.

[11] Other meditations on the subject include Louis Finkelstein, “New Look: Abstract Impressionism,” ARTnews 55, no. 1 (March 1956): 36; John L.H. Baur, Nature in Abstraction: The Relation of Abstract Painting and Sculpture to Nature in Twentieth-Century American Art, exh. cat. (New York: MacMillan, 1958); Lawrence Alloway and Harold Cohen, Abstract Impressionism, exh. cat., (London: Arts Council of Great Britain, 1958); Robert Rosenblum, “The Abstract Sublime,” ARTnews 59, no. 10 (February 1961): 38-42.

[12] Freilicher, letter to Ashbery.

[13] Willem de Kooning, interview with David Sylvester, “Content is a Glimpse,” recorded March 1960 in New York City, broadcast December 1960 on BBC as “Painting as Self-Discovery.” Edited version assembled from excerpts first published as “Content is a Glimpse,” Location 1, no. 1 (Spring 1963): 45-52. Republished in David Sylvester, Interviews with American Artists (New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2001), 43-57.

[14] “Donald Droll just called me to tell me that he had dinner with Bill de Kooning who was raving about my show which I suppose is immodest of me to repeat but why shouldn’t one take the good with the bad.” Freilicher, letter to Ashbery.

[15] Sarah Roberts and Katy Siegel, eds., Joan Mitchell, exh. cat. (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, 2021), 43.

IMAGE CREDITS

(fig. 1) Courtesy New York State Archives, Aerial photographic prints and negatives of New York State sites, 1941-1957, B1598-99. Box 11, no. 7.

(fig. 2) Courtesy Harrison Starr and the Woodberry Poetry Room Collection, Harvard Film Archive, Harvard University. © 2023 Harrison Starr.

(figs. 5–7, 11): Photos: Diego Flores. Courtesy the Estate of Jane Freilicher.

(fig. 8) Photo: Christopher Stach. Courtesy the Estate of Jane Freilicher.

(fig. 9) © 2023 The Willem de Kooning Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital image © Whitney Museum of American Art / Licensed by Scala / Art Resource, NY.

(fig. 10) Collection of the McNay Art Museum. Museum purchase with funds from the Tobin Foundation. © Estate of Joan Mitchell / The Joan Mitchell Foundation, New York.

(fig. 12) Courtesy the Estate of Jane Freilicher.

Banner image: Jane Freilicher, Untitled (Mecox Bay and Field), c. 1958, oil on linen, 69 1/2 x 72 1/4 inches, 176.5 x 183.5 cm. Photo: Diego Flores. Courtesy the Estate of Jane Freilicher.

All artworks by Jane Freilicher © 2023 Estate of Jane Freilicher.