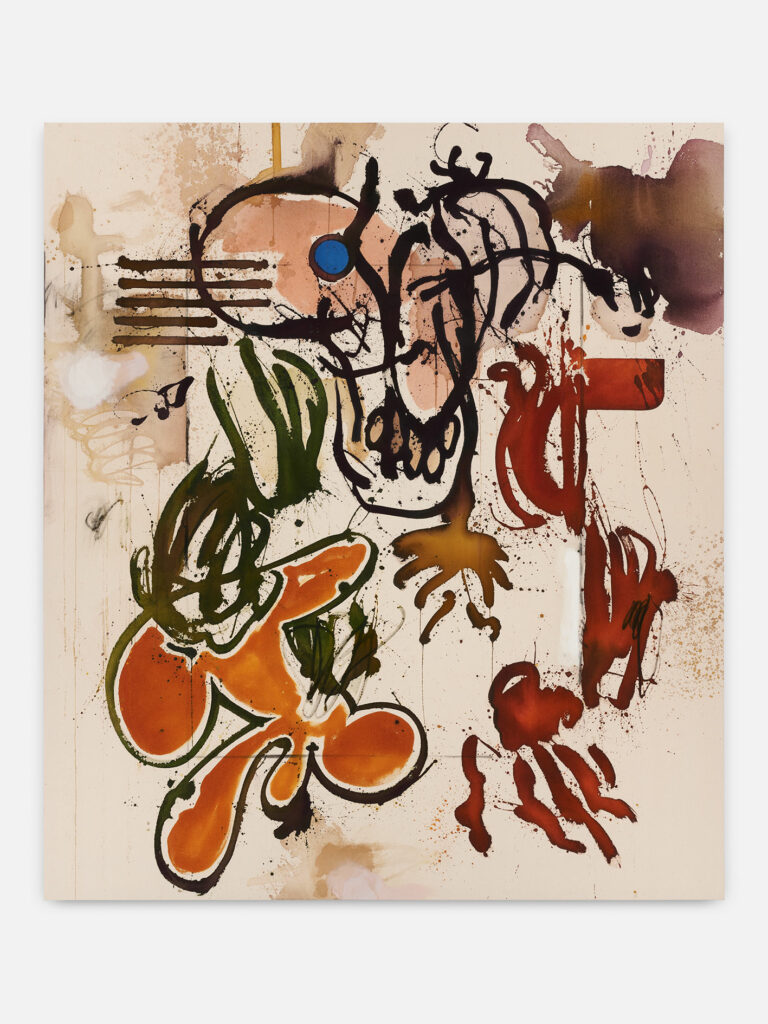

For Jan-Ole Schiemann's second solo exhibition at Kasmin, the Cologne-based artist spoke with writer, curator and artist Ryan Steadman about the formation of a new painterly language for his latest body of work. Jan-Ole Schiemann: New Paintings is on view through June 3, 2023, at 509 West 27th Street.

Ryan Steadman: It’s fascinating to look at this new body of work. Your older works were getting more and more dense and elaborate, and then you just opened them up.

Jan-Ole Schiemann: Like opening a window.

RS: Like suddenly you’re on top of a mountain, with fresh air all around. The older works are more like you’re in a punk club, shoulder to shoulder with all of this crowded energy. Yet there’s still a ton of energy in this series, but this new openness is what really struck me.

JOS: It’s always about energy. I like that imagery of being in a really dense and narrow place, almost like a shoebox that’s filled with gesture and material that gets shaken up. In this body of work, though, I pulled away from the heavy layering. For some time, I preferred the noise, and then I just wanted the opposite—to get away from the digital aspects and the density of the older works.

RS: Was it in reaction to our devices, computers and phones, these screens we spend so much time on?

JOS: When I started to color these fields in the large paintings—when I made the first yellow stripe—I stood in front of it and had a bit of an epiphany. I loved to stand in front of it and not see anything else. The work, in my studio, was suddenly about not doing things to the painting.

RS: It seems to be more about finding gestures and exploring the picture plane.

JOS: Right, and enlarging it in a way. These are 90 x 110 inches.

RS: Were you projecting your images in these new works?

JOS: No, at some point I started working with stencils. Well, this one, Vielgestalt im Zwischenreich (2019) was still derived from drawings and projected backgrounds, but with the Kavex Series [presented at Kasmin in 2019], I started working with stencils and moving away from the process of projecting. Instead, I’d create the shapes on the spot, on the canvas. I’d cut stencils from cardboard, compose the background and then layer the shapes. It’s a mixture of gestural line work and these more graphic lines that have been created with these shapes and stencils. I think that was, then, really interesting for me to have these two different lines of work touching.

RS: It’s so interesting how with a “new series” people don’t always realize that it’s just how the artist feels like working, “I’m sick of doing x and I’d rather do y.” You know, there’s nothing wrong with projecting images, but maybe you just got sick of that process.

JOS: This might be my greatest weakness, or strength, I don’t know, but I really get sick of doing the same thing. I tend to step away from processes that I’d do for quite some time, processes that I really explore, but then I’m done.

RS: You hit a wall.

JOS: Exactly. I hit a wall and then I go in the opposite direction. That’s the greatest thing about painting. For me, painting is about exploring what painting is, and what you can do with paint and these basic things like line work, shapes, and colors. I’m so interested in exploring that, way more so than creating a signature style. With this new work, my style is there and it’s recognizable (at least, this is what I hear from others) but this is not the main focus. It’s really about exploration and playing along with what comes out.

RS: Painting is a lifetime’s process. You’re learning; it’s your whole life. In the new works, was it kind of second nature that you’d keep a certain figurative element, especially in these hands or these cartoonish figures?

JOS: I wanted to reduce things. First, I wanted a two-color setup.

RS: That was my next question!

JOS: The other works have this grayish and transparent tone which refers to drawing a lot. Last year, or maybe the year before, I began to work with colored lines, which I did for quite some time.

RS: Right, and that might sound minor, but that’s actually a huge shift.

JOS: It was a big step. So I started to make colorful lines, it’s as simple as that. That kicked off a lot of questions and totally new horizons for me. In 2020, I had a show in Brussels, in which the works became way more colorful. I got rid of the gray layers. Then, in 2021, I started drawing with color. The setup for this show were these two complimentary colors: red and green. Since I was a teenager that combination has always been my favorite—I think I read somewhere that it was also Van Gogh’s favorite contrast, so I made it mine as well.

RS: I find red and green interesting because the values are so similar. As opposed to yellow and purple, red and green balance each other.

JOS: It’s true, they hold up to one another. They have a similar body.

RS: It’s clear that you come from a heavy drawing background, so adding this color had to begin with drawing. I didn’t realize at first how crucial that was in this series, and how it influenced your compositions so much. You’re not getting this crunched depth now. There’s this beautiful arrangement of things on a picture plane.

JOS: The picture plane became very important. It’s not the 3D chess that I was playing before. There’s some overlaps and bridging of forms, but it’s really laid out in a way that things sit next to each other.

RS: In older work, the architecture of the paintings was very structured and viewers could see that structure. Whereas here, in the new works, you have this interior rectangle to work from, but it’s really an invisible space. You called it a railing…

JOS: It’s a way for me to orient myself, to not spill all over the plane. I was trying to stay in bounds… and mark-making became much more important in the new works. I think painters can use the brush to create certain feelings. You can make an elegant gesture, or make a mark by being violent with the brush.

RS: It’s a painterly language.

JOS: Absolutely. So I had the two colors, and with all of these works, the first thing that I’d put down are these two “hands.”

RS: There’s a long, rich history of hands in painting. Fra Angelico used many disembodied and pointing hands to literally lead the viewers’ eyes. Similarly, Philip Guston used cartoon hands as a directional device but also as a symbol for ‘the artmaker’ himself. It’s a very open-ended symbol. You can use your hands for harmful and hateful things or beautiful, creative things like for making the works themselves; it’s very open and fertile.

JOS: It’s funny to have a gesture in a painting, a thing that you look at, that says “look here.” And of course, you paint with your hands, most of the time [laughs]. With these hands, I’m referencing decision making. Painting is about decision making. The Kavex works are matrices of decisions and dialectic processes of balancing and throwing things in one direction, then balancing it in another direction.

RS: I’m also thinking about hands in the context of AI imagery and the way that you can tell if an image is AI-generated is that the hands are always fucked up…

JOS: Right, they always add a few fingers or something. Obviously, I don’t do realistic hands, but it’s interesting how far you can go and it’s still recognizable as a hand.

RS: It’s interesting how that was your impetus for this, as you wanted to be more “hands on” with this new body of work and that this was kind of the moral of the story.

JOS: Right, but it’s not only the hands in the end. Though it’s not a whole figure, all of the works are in a way entities. They are personas, characters. I didn’t really think about what type of creatures or characters that I wanted to have, which was the cool thing about having this groundwork of the colors, because they let my subconscious do whatever. There’s all kinds of shapes reappearing that were there in my early works, and some new ones, which became more geometric here and there. I really wanted to retain all of that, but not reduce or be too strict about other shapes.

RS: As we were walking through the show, you mentioned using everyday things from your studio in the paintings.

JOS: Exactly, that’s how these shapes really came about. These circles, for example, are from bottle caps, lampshades, or salad bowls.

RS: At its most basic, that’s you wanting an organic and an inorganic shape together and in balance with one another.

JOS: You have to play with these contrasts. It’s what makes things interesting. You have this red and green; geometric shapes against organic shapes; and then colorfield versus line. They’re all playing together.

RS: Every interaction in the series feels like you’re very specifically setting up those interactions between color, shape, and form. It makes me curious: What artists are influencing you right now? And do you bring specific influences into your studio? This series is a fair shift for you, and I’m curious if any current or historical artists acted as an escape hatch for you?

JOS: I don’t know if there are specific artists, but I’ve always liked those old-school color field artists like Barnett Newman and Robert Motherwell. Helen Frankenthaler was definitely important in certain aspects, maybe Baselitz and Alechinsky, probably Günter Förg and Amy Sillman

RS: Newman, Motherwell and Frankenthaler specifically are really present here.

JOS: Yeah, so maybe those became more important to me, rather than Pollock or Gorky, who had been in the past. I’d never say that I oriented myself to them that much, though. I really adore their work and their way of working. I’m drawn to the way they work with color and the boldness and simplicity of the compositions. I’m impressed by that because my works were very dense and drawing-based. I always admire the opposite.

RS: When you’re deeply into something, you think that you’ve found “the way.” So when you see someone doing the opposite successfully, you think “how did they manage to use those methods to get something so exciting?”

JOS: Right, I always wonder how I can be so strict about these things. I have lots of catalogues and books in my studio but I don’t paint with them around me; I paint mainly from memory or from my mind. I never really think of working in the realm of Motherwell.

RS: You never set out to work and say “today I’m going to put 30% more Motherwell into the painting.”

JOS: [laughs] No, that’s stupid.

RS: At the same time, you obviously think deeply about these artists and their works.

JOS: Right, and then you have to try to forget. You soak it in and then forget. I like to pretend that it just wasn’t done at all. It’s more about cleansing your palate, actually. I think I did that with these works; I first cleared them all out.

Ryan Steadman is an independent writer, curator, and artist. He has written art criticism for publications such as Artforum, Cultured, ArtDesk, The New York Observer, and others. As a curator, he has organized a series of acclaimed gallery exhibitions, including his 2014 genre-defining group show “Ain’tings,” “Save It For Later” at the Sotheby’s S|2 galleries, and “RE(a)D” at the Nathalie Karg Gallery. He has also shown his own artwork regularly since 2001, with solo exhibitions at Karma, Halsey McKay Gallery, and Europa.

Studio photography by Mareike Tocha.