On the occasion of Sara Anstis’s first solo exhibition at Kasmin, writer and editor Philomena Epps joins the artist in her London studio. Exploring the process behind Anstis’s sensuous soft pastels and oil paintings, the pair discuss mythology, ecology, and the importance of sifting away the unessential when rendering her otherworldly figures. Visit the exhibition Procession at Kasmin in New York from September 8–October 29, 2022.

PHILOMENA EPPS: You grew up on Salt Spring Island, off the coast of Canada. How did that landscape inform your imagery?

SARA ANSTIS: There’s often a close cropping of the space around the figures, which I relate to the feeling of being surrounded by water. Growing up in a beautiful place with a small cast of characters gave me an appreciation for the aesthetics of claustrophobia. I favour the possibility of landscapes contained in the crook of an arm or glimpsed over a shoulder, a landscape in many parts that is determined by the placement of a figure.

PE: Although you have recently started depicting landscapes, hillsides, and other earthly terrains, a body of water is never far away. The figures in the paintings often appear either partially submerged, floating within its depths, or are situated at its edges.

SA: Right, and the feeling of being near water is appealing to me. In the paintings, this element has ambiguous effects, vacillating between inflicting pleasure and pain, such as in Legs (2022) where the immersed person might either be holding up their friend or being drowned in their embrace.

PE: The same unsettling ambivalence between innocent play and physical aggression occurs in Lily (2022), where the figure on land places their hand on the head of the one in the water. I read a text where you refer to these characters as “conduits for my autofiction.” What is your relationship to fictional narratives, particularly to otherworldly fantasy?

SA: The paintings make up a place that appears otherworldly, but the raw components that compose them are familiar to me. These situations unfold in confusing ways, but remain rooted in a reality that I actively experience and create, which is why autofiction resonates with me. Sometimes I wonder if the figures will start fighting wars, like Henry Darger’s Vivian Girls, but I don’t think their world is a prescriptive one with sides to choose. The characters are always changing.

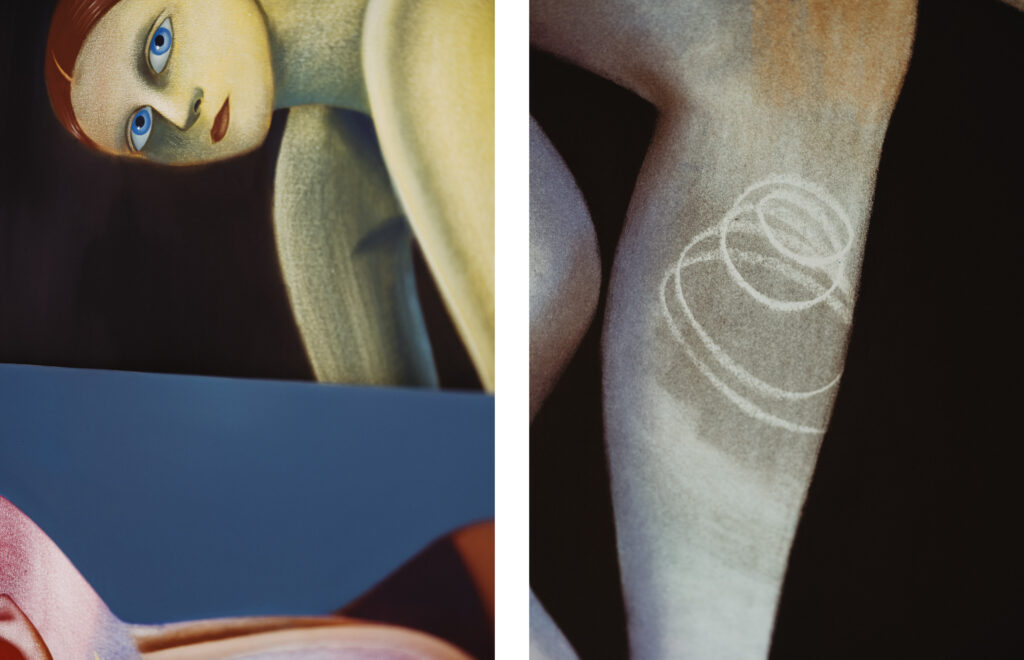

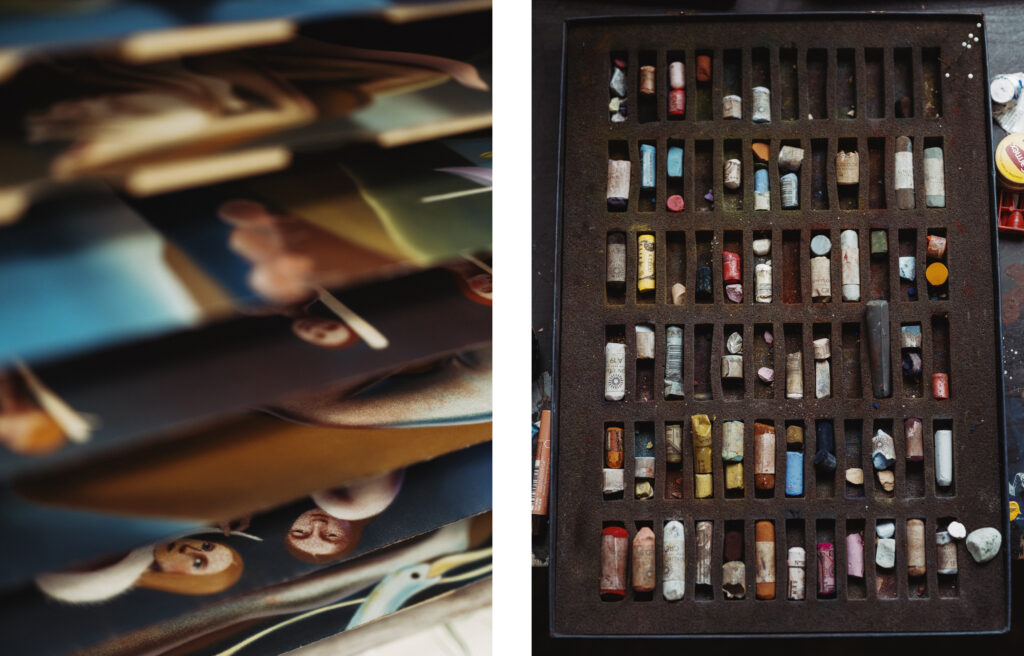

PE: In addition to making small paintings using soft pastel on paper, for this exhibition at Kasmin, entitled Procession, you have also made a series of larger oil paintings on canvas. In the latter, these painted bodies have shadows, scribbles, and sketches on them, while other parts of the canvas are left raw. Could you talk about the process of translating the aesthetic you have mastered in pastels into paint?

SA: Pastel is what I was using when I started focusing on color, so it has informed how I handle paint, or how parts of the canvas are left raw. Leaving parts of the canvas naked lets the painting breathe. The texture of these areas is constitutive of the image. When I start a painting, I make marks and scribbles or pour paint to create a structure to build on or reject. Some of these marks come through in the finished painting while others are covered.

PE: You’ve previously compared paper to skin, identifying the visceral sensuality which runs through all of your work. When working with pastel, the active physicality of rubbing and using your fingers seems both exacting and demanding, straddling the line between freedom and finesse.

SA: When a pastel painting is finished, the whole surface has been touched with my fingertips. That’s an indulgent thought but I do need to have that direct contact with the paper. It’s a repetitive process to get the pastels to sit right. Sometimes I have the refrain of a Peaches song on repeat in my mind when I’m working: “Rub rub rub rub rub rub rub bitch rub, Rub rub rub rub rub rub rub bitch rub.” There is a lot about pleasure and touch in the paintings, not only in the image, but also in the process of making it.

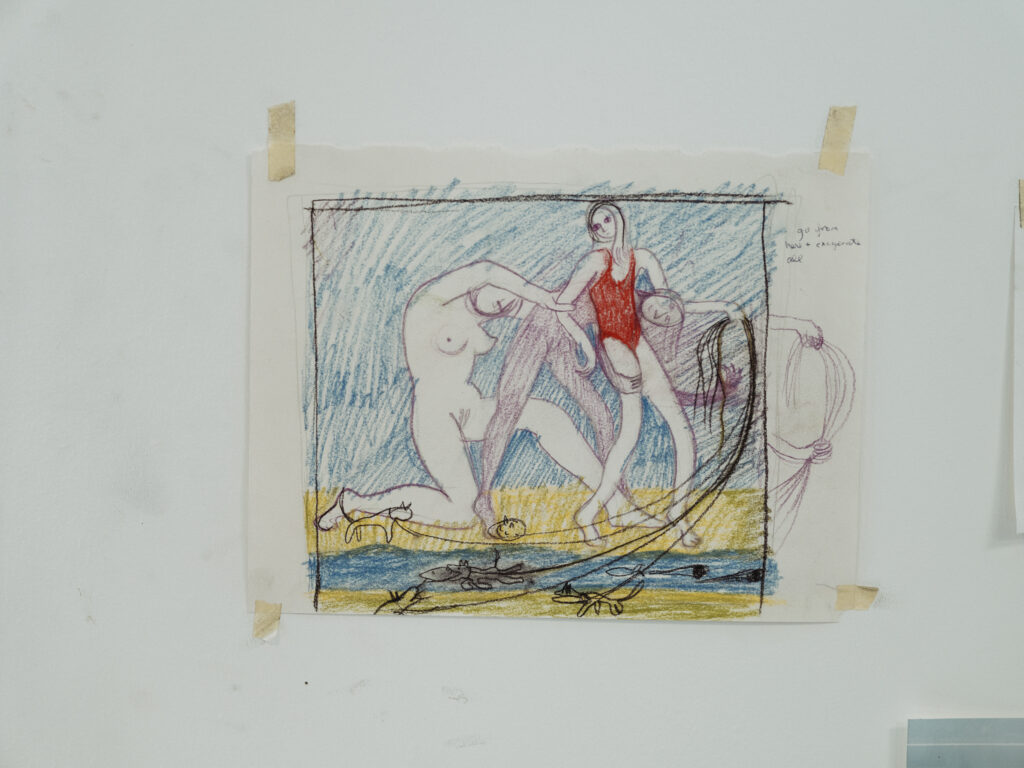

PE: How do these painted scenarios emerge? Do you visualize them as fully formed scenes, or do they slowly build, becoming a composite of different thoughts and references? In this show, the mythology surrounding the plant and animal life that exist within the forest seems dominant.

SA: They are built in different ways. Often they develop through the gestures and expressions of the figures and gradually turn into a situation in which there is enough of a story to keep everyone occupied. Forests are great storytellers. They are made up of countless compositions. I think my desire to live in a forest, alone, surviving on fish and tales, is translated into paintings that can actually last and sustain themselves, both materially and narratively.

PE: You’ve cited Eros and Thanatos as being a driving force in your practice, and there are numerous other oppositions in your work: darkness and light, land and water, pain and pleasure, aggression and care, morbidity and cheer. Despite the harmonious color palette and a sense of pastoral beauty, the paintings featured in Procession are evocative of death, suffering, alienation, and other hardships. There are clear scenes of mourning, in addition to instances of both overt and latent violence. Bodies are pushed into the water, a stake is being pulled out of a leg, or others are engaged in funerary rites.

SA: When I was in graduate school, a friend of mine died and a tutor guessed that it would come up in my work when I was ready to process the event, and they were right—she has come through in many of the more sombre works, where there is a dead woman and confusion. Last year, in 2021, Sabina Nessa and Sarah Everard were murdered in two separate cases of highly publicised gender-based violence in London. They and others come through in these images, too, without it being intended. These structures of feeling inform the time in the studio. When I speak about how these occurrences feed the paintings, I wonder if I want to let specific occurrences inform how they are read, because I am not trying to make paintings about a precise event, or to convey a certain thought. But there is a whole world happening in them, where a death prompts a procession and is treated with redemptive ceremonies that are unknown to the viewer and myself. When working on the show I noticed that there was a heavy sense of mourning in two of the works, in The Visit (2022) and in The Knot (2022), and that the figures in other works were quite determined to get somewhere. The Itinerant Mourner (2022) has a strong sense of direction, and a walking stick. I only realized that the procession was already passing by when I was nearly done with the work for the show.

PE: Yes, The Itinerant Mourner is akin to the travelling pilgrim. It also brought to my mind the folkloric figure of Dick Whittington, typically portrayed with his bindle and his loyal cat. I like this phrase that you just used: “a death prompts a procession.” It seems to offer a poetic interpretation of the show at large, and the works’ incidental relationship to one another. They function like the vignettes one might find in a mediaeval tapestry or a filmic storyboard. Throughout each painting, there are clues that we are viewing scenes that all exist within the same universe, with the recurring use of sticks, blue twine, fur, plant life, fish, dogs…

SA: What you’re referring to as clues—these recurring elements that are found across multiple paintings—are found early on in the process of working on a show, in drawn notes and in small pastel on paper works. Sheila Heti in her novel Pure Colour refers to life as a first draft, and artworks as second drafts, the polished versions of what we would like life to be like. The sticks, the blue strings, and the stooped postures of the figures in many of the paintings, among other motifs, are elements that have been found through drawing and have gained importance by slowly sifting away the unessential. This language changes from exhibition to exhibition, but some elements remain. Every show is a relief because it means I’ve figured something out, or at least deluded myself into thinking that I have, and I can let it go and start again.

PE: When we first met, we discussed the differences between an unencumbered nakedness, which I found your characters embodied, as differing from the idealised ‘female nude’ trope in art history. I also later wondered about your disinterest in portraying clothing and whether their nakedness is related to portraying sexuality or an inherent eroticism?

SA: I don’t see the need for clothing in the context of this world. I avoid eroticism and am more inclined to think of the figures as sexed. They have body parts that are subject to change, that can grow and become slick or recede completely at their will. I often forget that the figures are not clothed. They wear the clothes of nakedness. In Plato’s Charmides, the narrator comments that if the handsome young man engaged in conversation were to remove his clothes, one would not pay attention to his beautiful face as his body would steal the attention. Similarly, the faces of my figures are masked by the many faces of a naked body. Nipples in particular become eyes with their own gaze.

PE: This notion of changeability is perhaps related to the instances of corporeal ambiguity in your work. The characters are shown as embedded within a wider animal world, with fish nibbling their fingers, and dog-like creatures draped around their necks or carried on their backs. In contrast to this plethora of pelt, the figures are smooth and hairless, aside from the hair on their heads, which is often long and lustred.

SA: They are indeterminate beings. The hairlessness perceived by a human eye might be visually redressed by the hairy species the figures carry during the procession. As paintings, they are looking for the pleasure of juxtaposed textures and sensations: fur on bare skin, the grainy surface of the pastel rubbed into paper, smooth skin interrupted by sharp spikes and hairs, affection and remorse.

PE: I’m also struck by their bodily dynamism—how they are rendered as strong, lean, and flexible. They carry objects, crouch, hunch, swim, and kneel, all with a sense of ease and elasticity. How did you arrive at these poses?

SA: In this series of works, I wanted bodies that could occupy several temporalities, where they are crouching and standing up, about to depart and having just arrived. There are forces applying pressure to all of them and making them act and bend in strange ways, yet I am sure that they will make it through. They are strong.

PE: Finally, I wondered about your relationship towards the gaze? When the figures do occasionally meet the eye of the viewer, it feels fleeting, as if they have been caught in the act. Other characters are more unaware, or perhaps their closed eyes indicate something closer to avoidance or insouciance.

SA: In those moments of eye contact, it feels as though they become momentarily aware that they are under scrutiny. It reminds me of how in films someone being observed through a crystal ball will turn abruptly to look into the camera because they sense they are being watched. When the figures are looking straight out from the surface of the work, there is a sense of self-awareness, too, that they know who they are, what they’re doing, and that they cannot be touched or influenced. They are aware of their own power.

*

Philomena Epps is a writer, art critic, and researcher living in London. She is currently undertaking a PhD in the History of Art department at University College London, funded by LAHP, on the work of Alina Szapocznikow and Hannah Wilke. Her art criticism and writing has been published by Artforum, ArtReview, Flash Art, and Frieze, among others. She has also contributed texts to books published by Phaidon Press and Ridinghouse.

All studio photography by Benjamin McMahon, 2022