On the occasion of Mark Yang’s first solo exhibition at Kasmin, Birth, on view at 297 Tenth Avenue through February 17, 2024, Yang sat down with Jason Drill to discuss his evolving painting technique, moving to a new studio, and the value of keeping an open mind.

Jason Drill: The title of your show, Birth, alludes to a new phase in your practice. What would you consider the main themes or topics that the show covers?

Mark Yang: The title connects a running thread between the formal content of the paintings and my personal life. I didn’t start by thinking about a series or a theme. It emerged later. I try not to be too “in my head” in the studio, I try to be open-minded. I welcomed my first child last year, and I moved to a new studio. A lot has changed in a year.

Drill: Have these changes affected your artistic routine?

Yang: Sure. Parenthood is very difficult. I used to be in the studio 12 hours a day—sometimes not even painting, just looking and thinking about art. I don’t have that luxury anymore. Funnily enough my studio got smaller after moving upstate. I used to have about 500 square feet. Now I have about 350. But that’s life, right? Now I’ve learned to be efficient and practical in the studio. It’s a different way of working than before, but I’ve graciously adjusted to the new environment.

Drill: Your new paintings seem to be set in more defined environments, whether indoors or outdoors. Sleeping Couple looks like it’s set in the woods, Life (3) near a window of a building. Has moving to a new studio affected how you approach space in your paintings?

Yang: In 2023, I aspired to explore different spaces and contexts in my paintings. It’s easy to get comfortable when I find things that work, but moving upstate has helped me break away from that. That’s why I painted the woods and nocturnes. I had been too restrictive by telling myself that I’m an artist who makes figurative paintings, but there’s a transition that’s happening. I’m opening myself up—opening my space up.

Drill: Have you ever made sculptures? Could you see your work translating into three dimensions?

Yang: I made sculptures in college. They were plaster and wire figures that dealt with three dimensions, but that practice didn’t last too long. I enjoy looking at sculpture, though. You know, Michelangelo wasn’t a painter, he was a sculptor. He took jobs as a painter—that’s why he painted the Sistine Chapel—but he felt that painting was a lesser art. Still, he had to paint, so he invented a new technique which was basically a sculptural way of painting and drawing with planes. That’s how Picasso would draw, and I come from that tradition. That’s why my paintings could look more sculptural than not. I definitely see myself translating my paintings to sculptures in the future. I want to see my paintings come to life.

Drill: You presented two paintings in the group exhibition Somatic Markings at Kasmin in 2022. They were these conglomerates of arms, legs, and feet. No heads, no faces, just limbs suspended in space. But many of your new works show faces, and even when they don’t, the tangles of bodies feel denser than before.

Yang: I stopped painting faces in 2020. I wanted to see what my figures would look like without them. If you compare Italian to Dutch or Flemish paintings from the Renaissance, they appear very different. The colors are different, the settings are different. Those artists were painting their cultures. And as a Korean American painter who is an immigrant, I’m painting mine. But when I began painting figures, people started to notice that the facial features in my paintings looked “Asian.” Then the whole conversation became about that. There’s a lot of public discussion about gender, sexuality, and race in the art world, but I didn’t solely want to talk about my identity, that wasn’t my drive. So I removed the faces, I was literally hiding them. And when I removed them, the conversation about my paintings widened up.

Drill: What made you decide to reintroduce faces?

Yang: After a couple of years I thought, let’s try one again. The more you see Asian faces in Western painting, especially by Asian painters, the less novel they become. But it’s not like I suddenly started painting faces again—sometimes I show a face, sometimes I don’t. In Seated and Standing Nude, one of the faces is shown but the other is cut out. It’s a more figurative painting but there’s a little bit of a mix of that idea. I like that mix. I like to be experimental within the bounds of figuration. But within those bounds, I’m exploring different territories. For me, painting isn’t about the subject matter. Subject matter could be the first thing you see in a painting, but should be quickly forgotten. It acts as a vehicle to explore the possibility of diverse and peculiar content.

“For me, painting isn’t about the subject matter. Subject matter could be the first thing you see in a painting, but should be quickly forgotten. It acts as a vehicle to explore the possibility of diverse and peculiar content.”

Drill: Your figures often avoid clear assignments of gender, and in so doing, they have explored shifting cultural conceptions of masculinity and gender ambiguity. In your new paintings, even as we’re starting to see faces and genitals, your figures remain ambiguous.

Yang: I try not to think too much about who I’m painting. People ask, but it’s not my place to decide. Some people identify with my figures, and I embrace that, but it’s not my duty to assign anything to them. I started painting male bodies because that is what I have. I was actually surprised by some of the readings of my work. When you put a man next to another man, people in the U.S. have certain ideas about what that could mean. But in Korea, it’s totally different. Take sauna culture as an example—men will undress and shower together, they’ll wash each other’s backs. Or makeup—in the U.S. there’s a stigma around men wearing makeup, but it’s not the same in Korea. When I got married in Korea, I wore makeup. My wife even gave me makeup for this studio visit. There are different social conventions. In the U.S. these can be misunderstood, which informs stereotypes about Asian men in Western visual culture.

Drill: To what extent did these concerns inform your study of Western painting or art history?

Yang: I fell in love with art history for a number of reasons. I consider myself a Western painter. I was trained in that tradition and I embrace it. That’s why I reference more Western art history than I do Asian art. I saw many paintings in museums, but when I was first introduced to and learned about religious iconography in art history, I had a connection to those images. I grew up in a Korean American community, where it’s very typical to go to church. That’s where you meet other Koreans. My parents still go to the same church they joined when they immigrated to California in 2003. Religion really drove me, and art making is a really spiritual practice. It gave me a lens that I use to approach painting.

Drill: Can you give an example?

Yang: I went to school in Pasadena, near the Norton-Simon Museum. That’s where I saw Peter Paul Rubens’ David Slaying Goliath (c. 1616), and when I first looked at that painting I understood the story—of young David slaying giant Goliath after defeating him with a sling and five stones. But in the painting, David is huge. He has a muscular build and he’s really beating Goliath, which wasn’t the story. That’s not the David you read about in biblical stories. Now the painting is not just about David, but it’s also about the body—it’s about what the body could be, about idealized beauty. That’s when I realized that, when you’re making art, you don’t have to stick to the original story. That’s where self-expression can come in. The Old Masters were already doing it. Modernism just took it a step further.

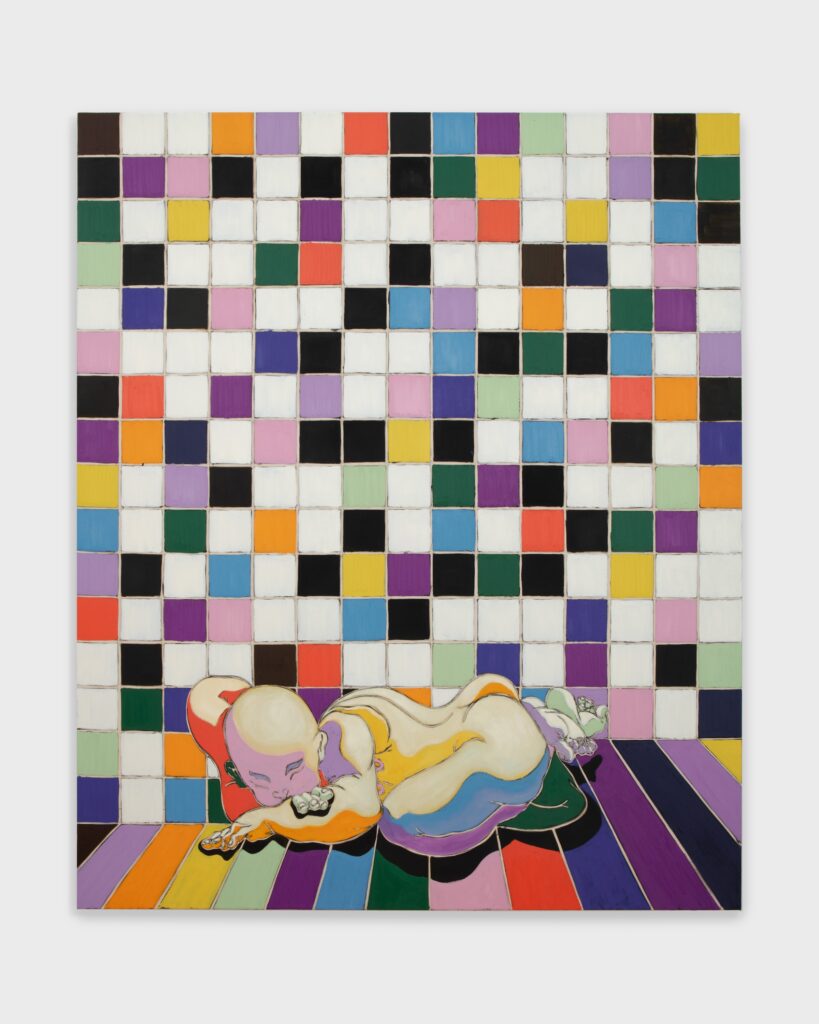

Drill: The new paintings expand your art historical repertoire. I see books on Tintoretto, Rubens, and Picasso in your studio. You’ve always pulled from Old Masters but now you’re deepening your engagement with twentieth-century artists. Kelly’s Colors for a Larger Wall is a prime example, making a clear reference to Ellsworth Kelly’s Colors for a Large Wall (1951), which is on view at MoMA. When did you first see Kelly’s work?

Yang: When MoMA reopened in October 2019 after its expansion and collection rehang. Kelly made a variety of works—I thought he mostly worked with single panels, but he made some multipanel works and Colors for a Large Wall is one of them. He painted each panel individually with chance, then displayed them in a random order. That was an interesting idea. For Kelly’s Colors for a Larger Wall, I knew I wanted a grid structure. I usually don’t fill up my canvas corner to corner with figures; I need to make space for the figures. I don’t always want to make a figure set in an incidental backdrop. That’s lazy. I want to make context for them—I don’t even like to call it background, because that makes the negative space less important. I’m trying out different spaces for the figures and one of the spaces I wanted to try was the grid.

Drill: Is that why you made the drawing after you started the painting?

Yang: Exactly. I started the painting by drawing a grid and the figure with charcoal. I’ve been drawing with charcoal ever since I started working with raw canvas in 2023. Then I painted every shape in black—I often paint in black to give myself a problem to solve. But I wasn’t sure yet what to do with the color. This was in 2023, the year of Ellsworth Kelly’s centennial. It was Kelly’s 100th birthday, but I was also celebrating the birth of my baby. I remembered Kelly’s painting and thought the grid could be a good context for the baby in my painting. So I made a work on paper, using Kelly’s colors to illustrate the grid—the drawing follows the pattern of Kelly’s painting more closely. Then I finished the painting. The grid on canvas doesn’t follow the same pattern as the one on paper, but I used similar colors on a wall larger than Kelly’s.

Drill: In your new paintings you’ve adopted a staining technique. When did you start staining your canvases?

Yang: Last year, in 2023. It allows me to draw freely on the surface. I feel very comfortable with charcoal and can draw well with it. But for some reason, when I’m painting, it’s easy for me to forget about my draftsmanship. I’ve tried to figure it out with paint and a brush. At some point I told myself to stop being stubborn and draw. At first I would get frustrated with charcoal because I was still gessoing my canvas. Gesso is hard to draw on because it gets dirty easily. So I decided to figure out a different way to draw on the surface. I’ll size the canvas with rabbit skin glue, which Renaissance painters typically used to seal their canvases. It’s used as a binding agent in traditional gesso recipes. But I won’t use gesso if I’m going to stain it, so the paint bleeds into the fabric instead of sitting on the surface.

Drill: It’s clear that you’re thinking about your materials and technique as much as you’re thinking about your subject matter.

Yang: Definitely. I got the idea of staining from Frankenthaler—you can’t leave her out when talking about staining. But I’m not trying to make a Frankenthaler. It’s all part of my visual vocabulary. I don’t just make a stain painting. I make sure it works, then I see where it leads. Life (3) is a good example. That one went through a lot. At one point I had a color gradation, then I had some geometry going on, and finally I could see figures forming. It was as if the figures were coming out of the center. I’ve always liked that inside-outside logic, and it’s something artists have historically used. For me, it symbolizes a kind of coming out—a birth of sorts.

Mark Yang (b. Seoul, South Korea, 1994) creates colorful, incongruous arrays of anonymous limbs entangled together, investigating the nuances of human interaction through a critical lens of art history. Morphing and distorting idealized figures into conglomerates of body parts, Yang’s forms exhibit a sculptural quality, the result of the artist’s thoughtful rendering of plane, dimension, and space. Reducing, dismantling, and reassembling their limbs almost to the point of abstraction with a variety of painterly techniques, Yang creates characteristically mysterious compositions that are not immediately forthcoming with their narrative plot. With a comprehensive set of art historical references, from the Baroque compositions of Peter Paul Rubens to the postwar abstractions of Ellsworth Kelly, Yang’s anatomical abstractions have been praised for their complication of gender norms. Yang’s ambiguous bodily arrangements rarely depict his figures’ faces, prioritizing their bodies over their identities. Resisting homogenizing classifications, Yang calls attention to shifting cultural conceptions of masculinity between South Korea, where Yang was born, and the United States, where he was raised

Jason Drill is an art researcher and writer based in New York. He is Head of Research at Kasmin and holds an MA from the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU. His writing has appeared in The Brooklyn Rail.

Studio photography by Charlie Rubin.