Take a deep dive into Ali Banisadr's The Messenger with Storyboard, a new interactive digital feature that takes viewers on an immersive journey through a single work. This, the first iteration of the feature, reveals Banisadr's personal symbolism and the diverse art historical references informing this seminal painting.

Ali Banisadr’s “The Messenger”

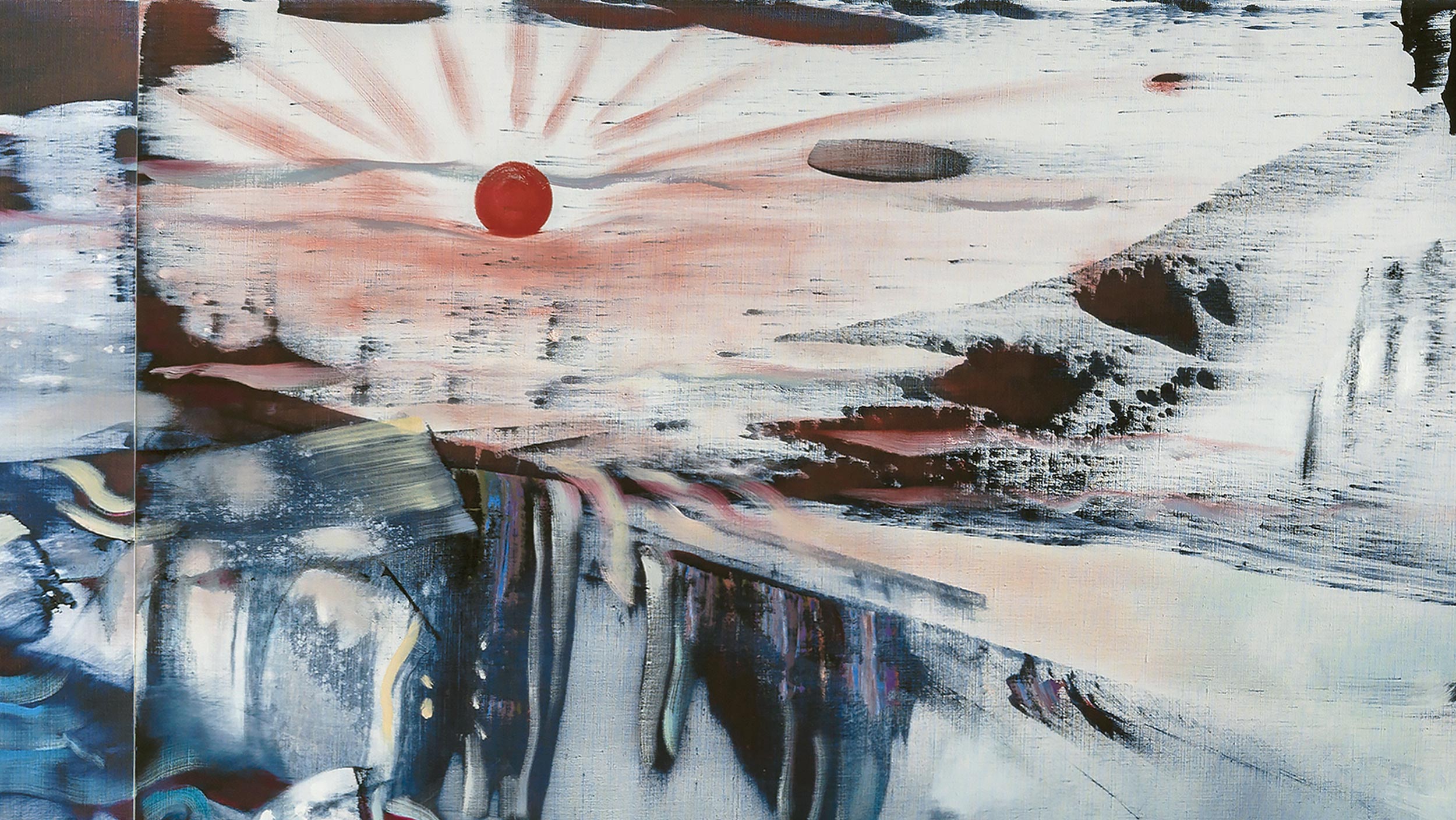

This is Ali Banisadr’s The Messenger, a diptych painted by the artist in early 2021.

Measuring 72 x 160 inches, this is Banisadr’s first two-panel painting in six years. Its large-scale picture plane is dominated by a palette of blues in various hues, combining to embody a powerful sense of motion.

Playing with a razor sharp tension between figuration and abstraction, the painting is realized through a combination of precise brushstrokes and sweeping gestural movements.

Banisadr’s work incorporates conflicting elements of scale, remixed so that no one perspective makes complete sense optically.

We might read these parts of the painting as semi-abstracted figures reaching, swimming, or bursting upwards.

Such ambiguous forms are a recurring motif of Banisadr’s work. Mythical and compelling, they resist total comprehension, fading in and out of focus like characters from memory or a dream.

This painting is the hallmark work of an exhibition that assembles varied art historical references with deeply personal symbolism to depict the artist’s inner visions.

The title of the exhibition, These Specks of Dust, encompasses all the senses in which the micro and macro inform one another, from the elemental minerals of pigment that constitute Banisadr’s painterly materials to the imperceptible cells of virus that defined the year in which the work was realized.

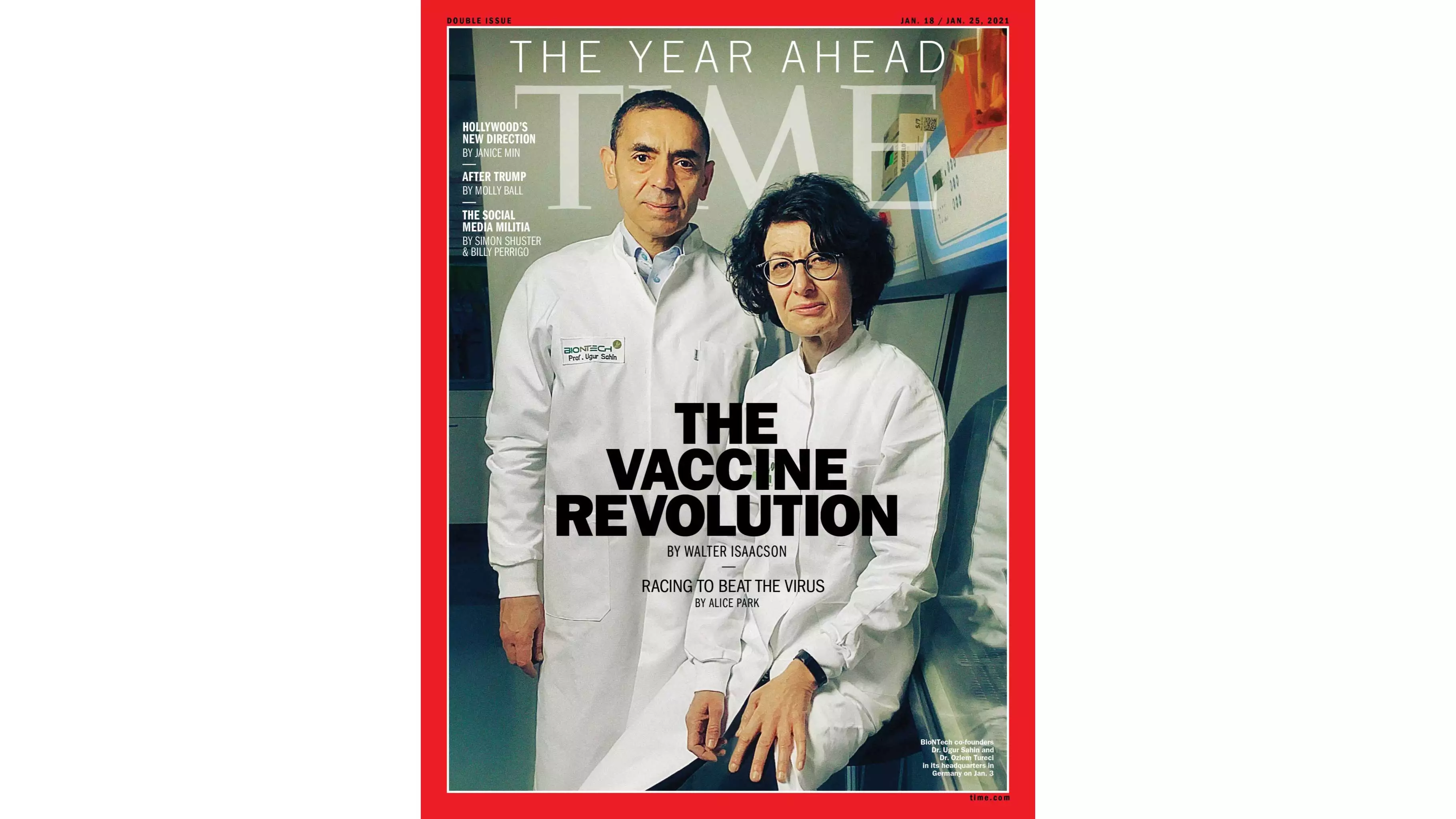

The Messenger’s title is a reference to the novel mRNA vaccine technology that has proven to be the defining tool in our battle against the coronavirus pandemic. It heralds the arrival of a new and prophetic force in what Banisadr believes is the quintessentially cyclical nature of our collective history.

Looking closely among Banisadr’s densely packed abstractions, one also notices the twisted chains of the DNA double helix running horizontally across the canvas.

They run parallel to delicately dashed blue lines, reminiscent of the slightest waves on a body of water.

The painting seems to move in every direction at once, as if the viewer finds themselves underwater in a rolling current, struggling to find the solidity of the surface.

Banisadr is based in Brooklyn, where his studio sits adjacent to his family home. The artist spent the majority of 2020 painting, channeling the tumultuous energies of the world as they shifted around him.

The studio is filled with ancient and contemporary references, books laid open, and what Negar Azimi has called “a catholic jumble of texts about symbology, color, Francisco Goya, the Timurids, Old Kingdom Egypt, and much else.” These function as inspiration and sustenance for Banisadr.

Measuring 160 inches in width, The Messenger draws its aspect ratio from both Picasso’s Guernica (1937) and Lee Krasner’s Combat (1965).

Banisadr’s absorption of Cubist and Abstract Expressionist explorations has been noted by poet and critic John Yau, who described this element of the artist’s charged, dynamic work as giving rise to a “metaphorical wind moving through his paintings.”

Yau goes on to say, “There are artists and writers who are able to create alternative worlds governed by their own ineluctable laws. This is the tradition that Banisadr has elected to become part of.”

A collector of stories and their archetypes, his works abound in references to ancient texts such as Gilgamesh and The Odyssey as well as to poet-painters such as William Blake.

Curator Joe Lin-Hill has observed that, “Philosophically, the observational point of view Banisadr establishes” as one that “unites past and present, near and far, micro and macro, the real world and beyond.”

Situating cyclical global turbulence in an ongoing context—likening human history to a narrative structure of climax and denouement—offers a framework for what might otherwise be categorized as meaningless chaos.

This flattening of memory and time forms a hybridized paradigm of fantasy, myth, and ideology that is reminiscent of The Torment of Saint Anthony, the first known painting by Michelangelo.

The monsters possess animal-like features including fish scales, amphibian digits, and erect bat-like ears. They struggle to destroy the saint as they carry him above a landscape that resembles the Arno River Valley near Florence.

Hybrid creatures reappear throughout history—and in Banisadr’s work—as both an embodiment of our unknowable biological past and the possibilities of a technologically inspired future.

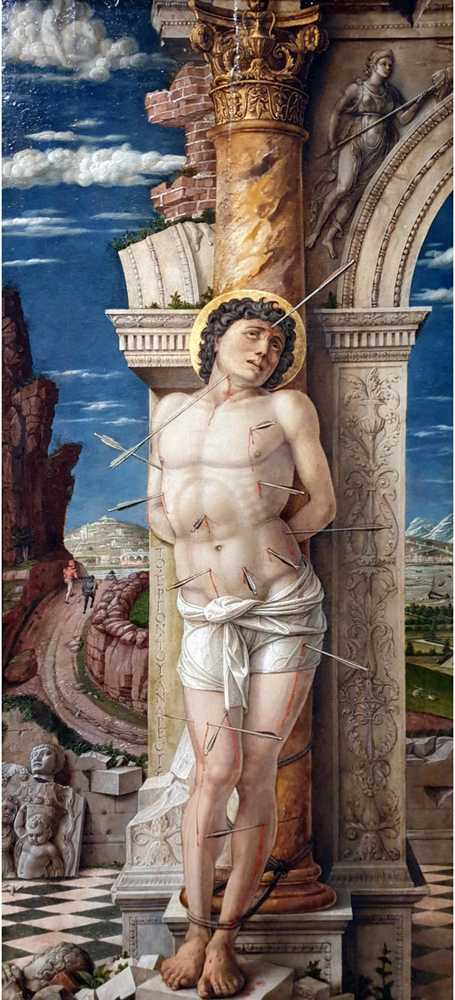

Many of these “figures” in The Messenger are punctured by lines reminiscent of spears or syringe needles.

This recalls the folkloric tales of Saint Sebastian, the early Christian martyr who survived an attempted crucifixion despite being shot in the chest by four single arrows. The arrows later became symbolic of the Black Death.

The color blue, which we might associate with water, abides in The Messenger. A symbol of wisdom and serenity, its tranquility balances the energetic force of the mark-making and reminds us of the elements of our natural landscape that we imagine most clearly as symbolic partitions: the sky and the sea.

On the very right hand side of the painting, we see a shoreline on which an intrepid explorer might arrive, shipwrecked or otherwise.

The artist’s recurring use of blue is also evocative of works from art history that explore the passing from one phase to the next by way of this partition.

Joachim Patinir’s Charon crossing the Styx (c. 1520-1524) depicts the famous ferryman of Hades who delivers souls from the world of the living to the underworld, a scene that is also described in Dante’s Inferno, a text that has informed Banisadr’s recent work.

Suspended between the bucolic wilderness of the left hand side of the painting and the burning darkness of the right, the figures partake in a ritualistic dialectic that encompasses all facets of human experience.

In The Messenger, a beacon—a glowing red sun—presides over the canvas from its position at the top edge. Its confident red bars signal a new dawn, or, perhaps, a new era.

Traditionally, a red sun has connotations of death and rebirth. Much like the Death tarot card, new beginnings are marked by the necessary close of a previous chapter.

The red sun, and especially the sunrise, are particularly poignant in Japanese culture. This print by master printmaker Utagawa Hiroshige depicts this moment on New Year’s Day.

Featuring a flattened foreground and the blush red of the rising sun on the horizon, the scene further compounds a sense of novelty and renewal.

Some of the painterly marks in The Messenger recall soundwaves bursting from a source, or the demarcation of music as written script.

As a child growing up in Tehran, Banisadr was exposed to the air raids, bombings and explosions of the Iran-Iraq war. While the sirens would blare outside, Banisadr would sit in the basement of his home and draw.

Banisadr credits these experiences with the development of his synesthesia, a condition that presents him with orchestrally-complex soundscapes that guide him intuitively to build up a painting’s composition.

It is this extra sense, curator Robert Hobbs proposes, that “has enabled him to focus on energy and rhythm as crucially important aspects of his innovative art.”

The Messenger brings into fruition a world that both draws on the fundamental truths of our collective history and yet reshapes the narrative possibilities of the future.

A small camp-fire burns at the heart of the picture—an existential pilot light that endures despite the tempestuous conditions that threaten it.

Ghost-like text akin to graffiti or cave painting melts into its lower layers. A note left for someone to find in the future, perhaps.

What role do artists play in moments of crisis? We might look to Ralph Waldo Emerson, a favorite of Banisadr’s, for an answer:

“Standing on the bare ground—my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space—all mean egotism vanishes. I become a transparent eye-ball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God.”

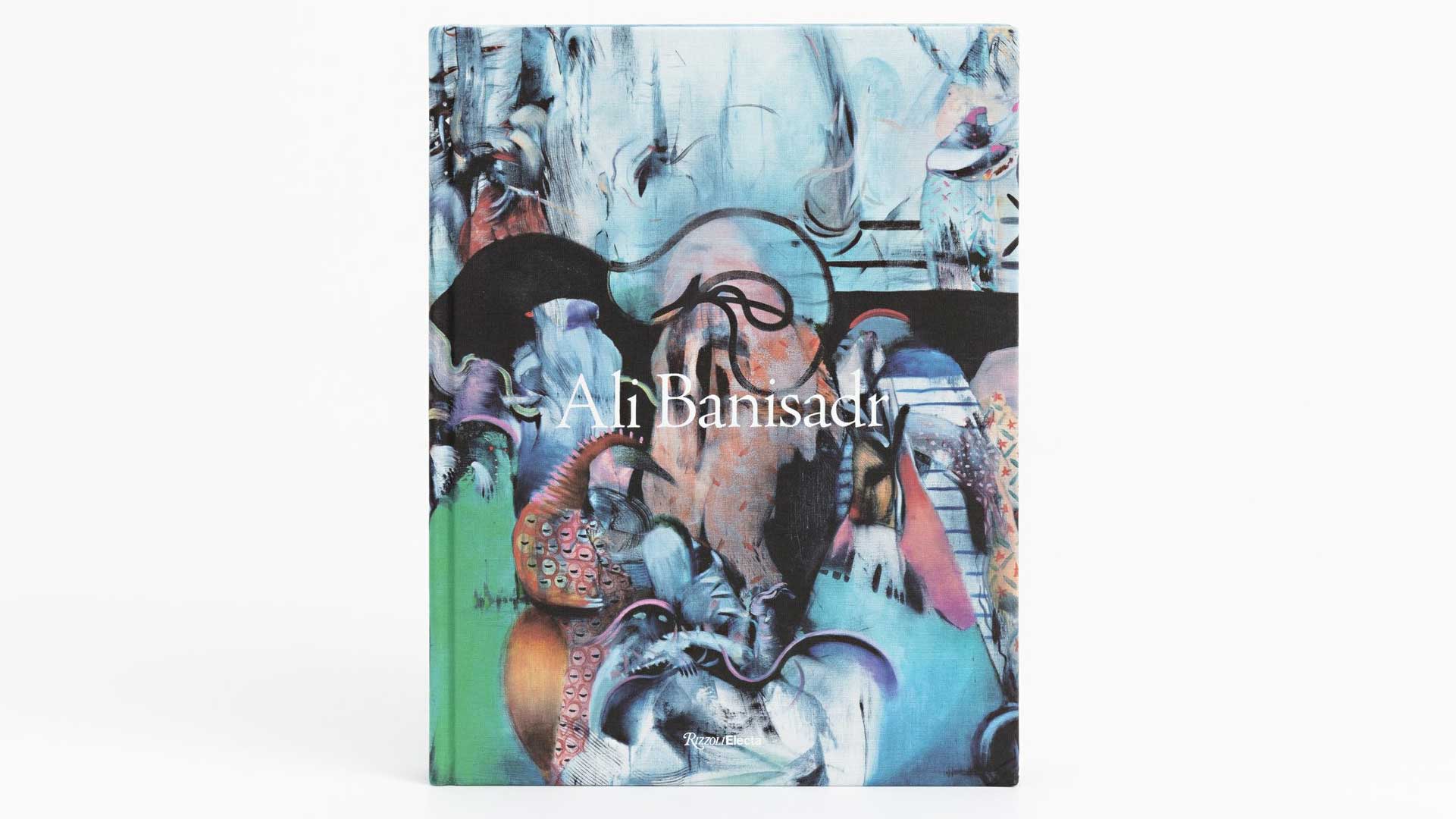

Negar Azimi, Joe Lin-Hill, John Yau and Robert Hobbs’ essays on Banisadr’s work can be found in his recently released monograph, published by Rizzoli, Ali Banisadr.

Image Credits:

Pablo Picasso, Guernica, 1937, oil on canvas, 349 cm × 776 cm. Photographic Archives Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia. © 2021 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Lee Krasner, Combat, 1965, oil on canvas, 179 × 410.4 cm, National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Felton Bequest, 1992 (IC1-1992), © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. William Blake, Jerusalem, Plate 1, Frontispiece, 1804 to 1820, Image Courtesy YCBA. Michelangelo, The Torment of Saint Anthony, c. 1487-88. oil and tempera on panel, 18 1/2 x 13 1/4 in., Kimbell Art Museum, Fort Worth. Andrea Mantegna, St. Sebastian, 1457/1459, oil on wood, 300 x 680 cm, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Austria (GG 301). Joachim Patinir, Charon crossing the Styx, 1520-1524, oil on panel, 64×103 cm., © Museo Nacional del Prado. Utagawa Hiroshige I, Sunrise on New Year’s Day at Susaki (Susaki hatsu hinode), 1853, woodblock print, 21.9 x 34.3 cm.